Agnieszka Zalewska: The first woman and the first Pole to preside over CERN’s council

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.0097

An experimental particle physicist whose focus has evolved from silicon tracking detectors to neutrino physics, Agnieszka Zalewska has enjoyed an association with CERN since the early 1970s, when she analyzed bubble chamber data for her PhD work at Jagiellonian University in Kraküw. She has spent most of her life in that city, where she is a professor at the H. Niewodniczański Institute of High Energy Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Although Poland didn’t join CERN until 1991, the country’s particle physicists have worked with the lab for much longer. In particular, experimental physicists there specialized in analyzing many-body events produced in hadron collisions. ‘Looking at these events became a local specialty,’ says Zalewska, ‘maybe because it was less attractive to physicists at CERN.’ For Polish physicists, she says, such analysis provided ‘a possibility to work on real data. It was contact with real life. We were able to do interesting things concerning particle correlations in high-multiplicity final states. The collaboration was a common interest.’

Physics Today‘s Toni Feder spoke by phone with Zalewska about her life in communist and postcommunist Poland and her goals as president of CERN’s council, which includes representatives from each of CERN’s 20 member countries.

PT : How did you happen to go into physics?

ZALEWSKA : I was generally interested in science since quite early. Somehow in a certain moment I realized the beauty of physics, which lies in the fact that you can use mathematical descriptions to explain phenomena you see around you. I think it was also quite important in the 1960s in Poland, we got quite a lot of mathematics and physics as part of our general education, and quite often it was on a good level.

PT : How did the country’s politics influence you?

ZALEWSKA : We lived a kind of double life. It was a communist country, so you led an official life, and a completely different life in private. Privately, the whole system of values survived. Dreams about different ways of living survived. In principle, those two lives were quite separate, existing in parallel. Of course, it didn’t work so nicely all the time.

For example, I was one of the best students in my year of physics, so I had a special stipend. At a certain moment I lost the stipend because the communist youth organization decided my ideology was not proper, that I was not somebody who should teach students in the future.

PT : What were the consequences of losing the stipend?

ZALEWSKA : At first I was upset because I had the impression that it would limit my possibilities. But it didn’t. That was a surprise. Just after I got my first job [as a PhD student] at the Institute of Nuclear Physics, a professor asked me to take care of student exercises in the laboratories at the university. I said yes, but told him I might not be allowed to. I ended up overseeing the laboratories for three and a half years. It was important that we [students and young researchers] knew well that our professors were privately thinking like us. And I understood that the system had begun to degenerate: There was no connection between the decision of the communist youth organization and what I could do at the university. It was a very important discovery that the system was not so tight.

PT : Did you feel there were challenges for you as a woman in physics?

ZALEWSKA : Not at all. In Poland, there was a long tradition for women to have positions of responsibility. This tradition helped women get an education. It was accepted by society.

We were many women studying physics. But very often they were choosing to teach physics in schools. It was not so often that they would choose a scientific career.

PT : How have you managed to balance your professional and personal life?

ZALEWSKA : First, I have an exceptional husband, who always supported my professional development. He is also a physicist, a theoretical particle physicist. But he is 13 years older, so when we got married, he was already well known as a physicist, with some important publications. The other important aspect was that I always stuck to working 8 hours solid in my professional life, and then was dedicated to my children when they were small.

I have four children. They are all adults now. One of my daughters has a PhD in mathematics and is a licensed actuary; the other is a veterinary doctor. One son is an architect, and the other, also a PhD in mathematics, works for Google. They have all somehow found their place here in Poland.

PT : Why was it significant that your husband—Kacper Zalewski—had already established his career when you married?

ZALEWSKA : He was invited to foreign universities and conferences. Coming back with a few hundred dollars meant a fortune in the 1970s. This enabled us to have a big family. It meant we had no financial difficulties. When he came back after a month working abroad, I could pay the salaries of nurses and for a nice kindergarten. This was very important. My salary at that time was the equivalent of $10–$20/month—enough to support one person.

Even more important, my husband was supportive of me. I remember a critical moment, when the nurse got seriously ill and I was teaching and had some other obligations, I told him that it didn’t make sense, because nothing was going well. I thought I would be happier staying at home and forgetting about my profession. He told me I could do whatever I want but he thought I would be unhappy to quit. The psychological support was very important.

PT : How difficult was it to obtain visas for travel outside of the Eastern bloc countries?

ZALEWSKA : It varied. From the Polish side, it was a question of how easy it was to get a passport. I never signed anything I would now regret. Scientists were not considered as politically dangerous. At times it was very good for the government to show us freedoms.

In 1974 I went with my husband and then two-year-old daughter to the United States for three months. We were invited to the University of Washington. He got so many invitations to give talks at universities that we decided to go by car from Seattle to New York. We went to California—Berkeley and Davis—then to the national parks, then through the Rocky Mountains to Fermilab. To Niagara Falls, on the way Rochester, Cornell, and Brookhaven. It was the journey of our lives. We had this feeling that it could never happen to us again. Nobody thought that Poland would see the political change that came later, that we would become a normal country. Communism seemed quite solid at the time.

PT : As far as juggling physics and family, you also selected research areas that suited your personal needs.

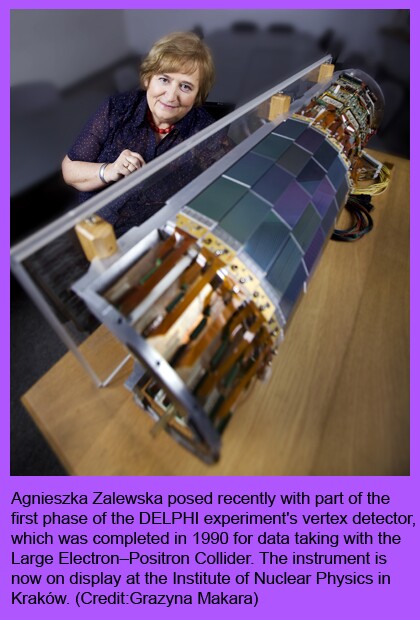

ZALEWSKA : Yes. Polish physicists already had a solid reputation in data analysis. Then, in 1981, my boss came from CERN with the information that he had been invited to prepare a group of people to join a LEP [Large Electron–Positron Collider] collaboration—it was the future DELPHI experiment. He said, ‘I am looking for volunteers. You should consider there will be no publications for some years.’ I decided this was something for me, because I had small children, and the experiment will grow together with my children. With time, I will have more time for the collaboration. It was correct thinking. We constructed detectors. I was able to go to CERN for one or two months every year. Then the whole family went in 1986–87, for almost two years. We did pioneering work on silicon detectors with microelectronics for DELPHI.

I became known because of this work on the DELPHI silicon vertex detector; it was for measuring precisely the vertices of particle interactions and decays inside the accelerator tube.

PT : How did you get into your current research area, neutrino physics?

ZALEWSKA : In the 1990s I went for a second time to CERN for one and a half years. I worked again for the DELPHI experiment, being responsible for software and data analysis from the vertex detector. Soon I became a member of CERN committees. I learned a lot and loved it.

At the time, the neutrino program for Europe was born. I decided it looked interesting and I gave talks in Poland to inform my colleagues something was happening. I didn’t think of it for myself. But there was an interesting discussion after my seminar in Warsaw, and I got involved. This was completely unexpected for me.

Part of the reason [for my switch to neutrino physics] was that I had been considering working on a silicon detector for the International Linear Collider. It was clear that the ILC was moving slowly, and you couldn’t say when it would be built. In neutrino physics, it seemed we could get data quickly. As part of a group of Polish physicists from seven institutions, I joined the ICARUS experiment [in which a detector in Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy lies in wait of neutrinos from CERN to study neutrino oscillations]. The whole thing was a success. The Polish neutrino group is quite active—we have also joined the T2K in Japan.

Now that we are involved in neutrino physics, we are thinking about a small underground laboratory in a copper mine in Poland dedicated to testing detectors and performing physics measurements. The site was considered for the future giant neutrino detector to work on the neutrino beam from CERN, but after a long discussion the Pyhäsalmi mine in Finland was chosen for further studies.

PT : What are your plans as president of the CERN council? And what challenges do you face?

ZALEWSKA : The next three years at CERN are rather well defined. Present plans assume that after data taking finishes in February 2013, we start the almost two-year-long shutdown for getting the Large Hadron Collider ready to work at almost its design energy of 7 TeV per beam.

The second task is working on the update of the European Strategy for Particle Physics. As the supreme decision-making body for CERN, the council is responsible not only for approving activities and programs of the laboratory, but also for defining Europe’s strategy for the field. With recent results—a Higgs-like particle found at the LHC, and the value of the third mixing angle for neutrinos from the Daya Bay and other experiments—we can plan better now how to proceed. The strategy should be finished next year, and then comes the question of implementation and money.

More about the authors

Toni Feder, tfeder@aip.org