A mineralogical carbon-capture method works—but not the way we thought

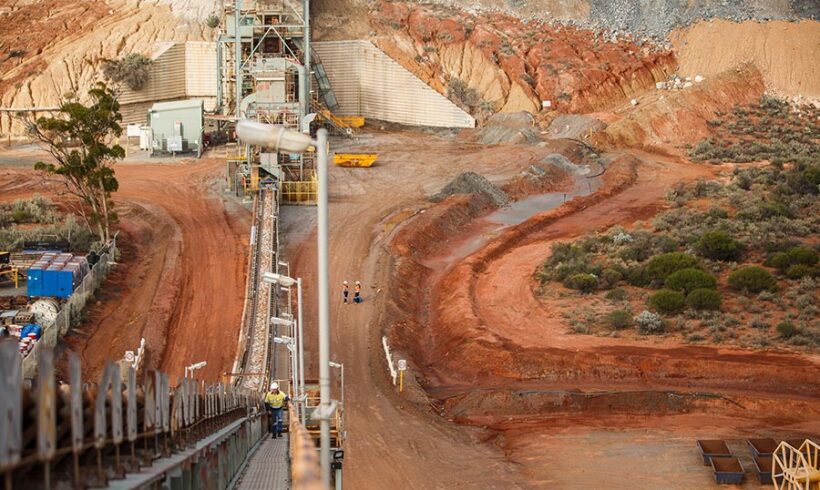

Aggregate processing at a gold mine in western Australia.

Courtesy of the University of Strathclyde

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report

Despite previous research exploring various minerals’ CO2-trapping ability, Mark Stillings, Zoe Shipton, and Rebecca Lunn of the University of Strathclyde in Scotland suspected that milling rocks in a CO2-rich environment does not create carbonate minerals, as many others had assumed. Instead, their new research confirms that it leads to the formation of chemical bonds that can lock in CO2 more tightly and in greater amounts than expected. And the process works especially well with some of Earth’s most common rocks—even ones lacking in calcium and magnesium.

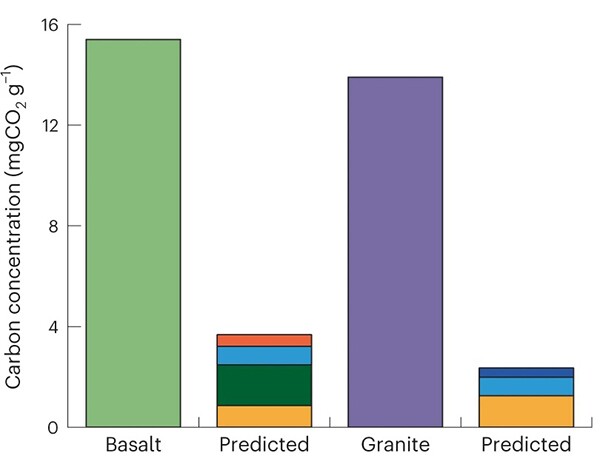

Unlike in past studies, the researchers tested not only individual minerals but also polymineralic rocks. They chose basalt, which is rich in carbonate-forming metals, and granite, which has barely any. When the researchers milled the samples in a room-temperature chamber of nearly pure CO2 gas, the basalt captured 15.5 mg of CO2 per gram of rock, about four times the expected amount based on measurements of basalt’s constituent minerals (see the graph below). The granite did nearly as well: It took in 13.9 mg/g, far more than carbonate-based absorption would allow. The milling results suggested that the CO2-capture mechanism is unrelated to calcium and magnesium content and flourishes in heterogeneous rocks. Spectroscopic measurements confirmed that neither the polymineralic rocks nor the individual minerals had formed carbonate minerals.

M. Stillings, Z. K. Shipton, R. J. Lunn, Nat. Sustain., 2023, doi:10.1038/s41893-023-01083-y

Stillings, Shipton, and Lunn performed additional experiments to help them identify the newly created CO2-incoporating structures. Among their findings is that basalt and granite have a stronger hold of their CO2 than do the individual minerals, which released most of it when immersed in water. The researchers conclude that during the crushing process, CO2 readily slides into minerals’ crystal lattices, sticking to the dangling ends of bonds that have broken under pressure. The polymineralic rocks are more effective at trapping and retaining the greenhouse gas because the CO2 binds tightly to charged silica and oxygen species that emerge at the boundaries between different mineral types.

Considering the ubiquity of basalt and granite on Earth’s surface, the researchers make the case for pursuing the rock-pulverizing technique on a large scale. Facilities that already crush rocks for use in construction could do so within a stream of pure or nearly pure CO2, and the ground-up rock would hold on to its CO2 even when subjected to heat and moisture. As a bonus, when exposed to water the basalt would leach calcium and magnesium, which in theory could be used to absorb more CO2 through the formation of carbonates. Unknowns about the practicality of the technique remain, however, including the energy and financial costs of finely milling all that rock.

Regardless of whether crushing rocks becomes useful for climate change mitigation, the new knowledge about CO2 uptake owes its existence to Mars research. Several years ago Lunn and Stillings—environmental engineers who have never studied planetary science—attended a conference talk in which the speaker explained how landslides and other rock-crushing processes on Mars were associated with localized changes in atmospheric composition. Applying those lessons to Earth, they and their colleagues wondered whether the energy released from rock fracturing was responsible for the curious acidification of groundwater in seismically active areas (it was

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org