A microscope for measuring surface acidity

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4788

Atoms and molecules, the invisible building blocks of everything around us, quickly become complicated as their size and numbers increase. A molecule of just two atoms can occupy any of a multitude of rotational, vibrational, and electronic quantum states, each with potentially different behavior in a chemical reaction. With lasers and molecular beams, physical chemists can prepare and probe many of those states individually and thus dissect the dynamics of a gas-phase molecular reaction in exquisite detail.

But when a reaction takes place on a solid surface—a common scenario in industrial catalysis, materials science, and geology—it’s much more of a black box. Because every atom on a rough, irregular surface is situated a little bit differently, they can have dramatically different reactivities, even to the point of steering the reaction toward different sets of products (see Physics Today, September 2018, page 17

Those chemical distinctions among surface sites are extremely difficult to assess directly. Experiments usually measure only the average reaction output for the whole surface; they can’t readily track individual reactant molecules to see where on the surface they reacted. Researchers are therefore limited in their ability to rationally design new solid catalysts, counteract corrosion on metal surfaces, and understand the weathering of rocks and minerals.

Now the Technical University of Vienna’s Ulrike Diebold, her postdoc Margareta Wagner, and their colleagues have adapted an atomic force microscope (AFM) to map a surface chemical property—proton affinity, otherwise known as acidity—with atomic resolution. 1

Acid–base chemistry—the transfer of an H+ ion from one molecule or surface site to another—is a fundamental feature of many reactions, and surface reactions are no exception. (For just one example, in the catalytic cracking of hydrocarbons, a solid catalyst needs to transfer protons from its surface to fill out the newly severed C–C bonds.) By separately measuring how readily each site attracts and releases protons, the researchers offer an unprecedented look at the sites’ respective roles in such a reaction.

Oxygen sites

Like many discoveries, the work grew out of research with a much different initial direction. Diebold, Wagner, and colleagues were studying water adsorption on surfaces of indium oxide. When doped with tin, In2O3 has the valuable combination of optical transparency and electrical conductivity, so it’s commonly used to make the top electrodes in solar cells and liquid-crystal displays. In its undoped form, it’s a transparent semiconductor used in some types of coatings. The Vienna researchers wanted to explore whether or how the material’s properties change when H2O clings to its surface.

Given its simple chemical formula, In2O3 has a surprisingly complicated structure. Each O atom is surrounded by four In atoms, but all four of those O–In bonds have different lengths. At a crystal surface, O atoms can occupy four geometrically (and potentially chemically) distinct sites—denoted by α, β, γ, and δ—depending on which of the four bonds is missing. Furthermore, some surface In atoms are surrounded by six O atoms, just as they are in the bulk, and some are surrounded by five.

In previous work, Diebold and colleagues observed 2 that when a molecule of H2O sticks to the In2O3 surface, it breaks apart into OH and H. The OH situates itself atop the oxide surface, with the O atom bridging two of the fivefold-coordinated In atoms and the H protruding upward. The split-off H then binds to a neighboring O atom on the oxide surface, which happens to always be one of the β sites.

The OH from the water molecule pokes higher above the surface than the OH on the β oxide site. “Initially we wanted to know if we could see the height difference with our AFM,” says Wagner. “That does not sound very spectacular, I admit.” But then they noticed something odd. The forces between the AFM tip and the OH differed markedly for the two types of OH site. For the water OH, the maximum force of attraction felt by the tip was around 150 pN; for the β oxide OH, it reached more than 250 pN.

When the researchers used the AFM tip to nudge the H atoms to different oxide O sites, they found that those sites, too, had their own characteristic attractions to the tip: 270 pN for an OH on a δ site, almost 350 pN for one on a γ site. (The α site proved too difficult to access and wasn’t part of their analysis.)

What’s more, those values were surprisingly reproducible, even across different experiments that used different AFM tips. “Usually, the chemical makeup of a tip—the atom or atoms at the tip’s apex that interact with the surface—is a big unknown in techniques like this, unless you functionalize the tip on purpose,” explains Wagner. “And chemically different tips can result in forces that differ by a factor of 2 to 10.” The tips appeared to be chemically identical, even though the researchers weren’t doing anything special to ensure that they were.

From forces to acidity

To find out what was going on, the experimenters turned to Bernd Meyer, a theorist at Friedrich–Alexander University Erlangen–Nuremberg. With density functional theory, Meyer calculated the forces between the OH groups on the surface and several hypothetical model AFM tips.

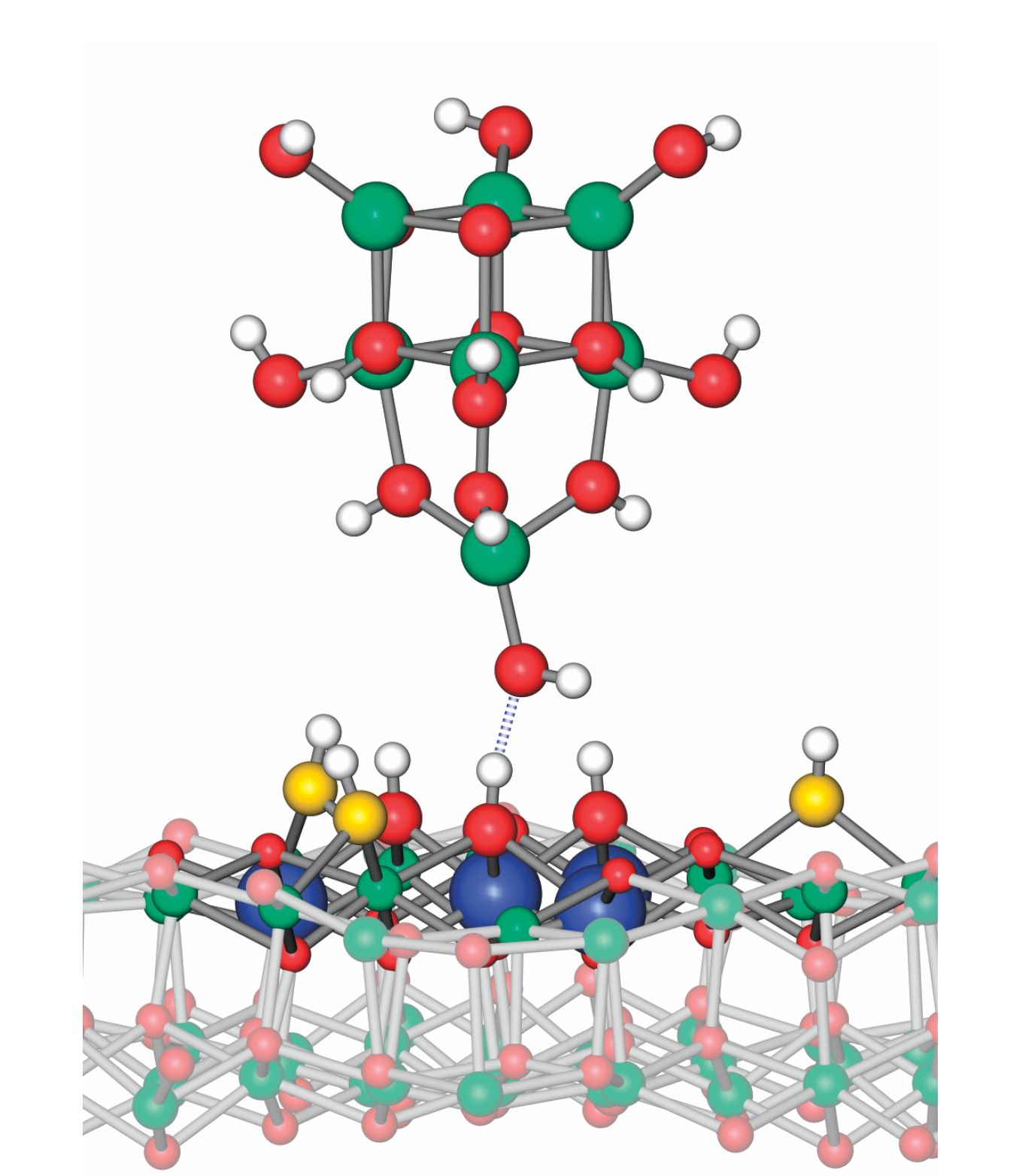

The best match to the experimental results came from a model tip, shown in figure

Figure 1.

Acidity microscope. When an atomic force microscope tip made of hydroxylated indium oxide descends toward a surface of the same material, the oxygen atom at the end of the tip feels an attractive force (dotted line) to a hydrogen atom on the surface below it. The force is related to the surface site’s acidity: how readily it releases its H atom in a chemical reaction. Indium atoms are shown in green and blue, O atoms from adsorbed water in yellow, other O atoms in red, and H atoms in white. (Adapted from ref.

As figure

The tip always loses the battle: The terminal O atom already has one H atom bound to it, so the attraction it feels to a second H is weaker than the chemical bond holding the H to the surface. In fact, the more strongly the H clings to the surface O atom, the more weakly it’s attracted to the tip.

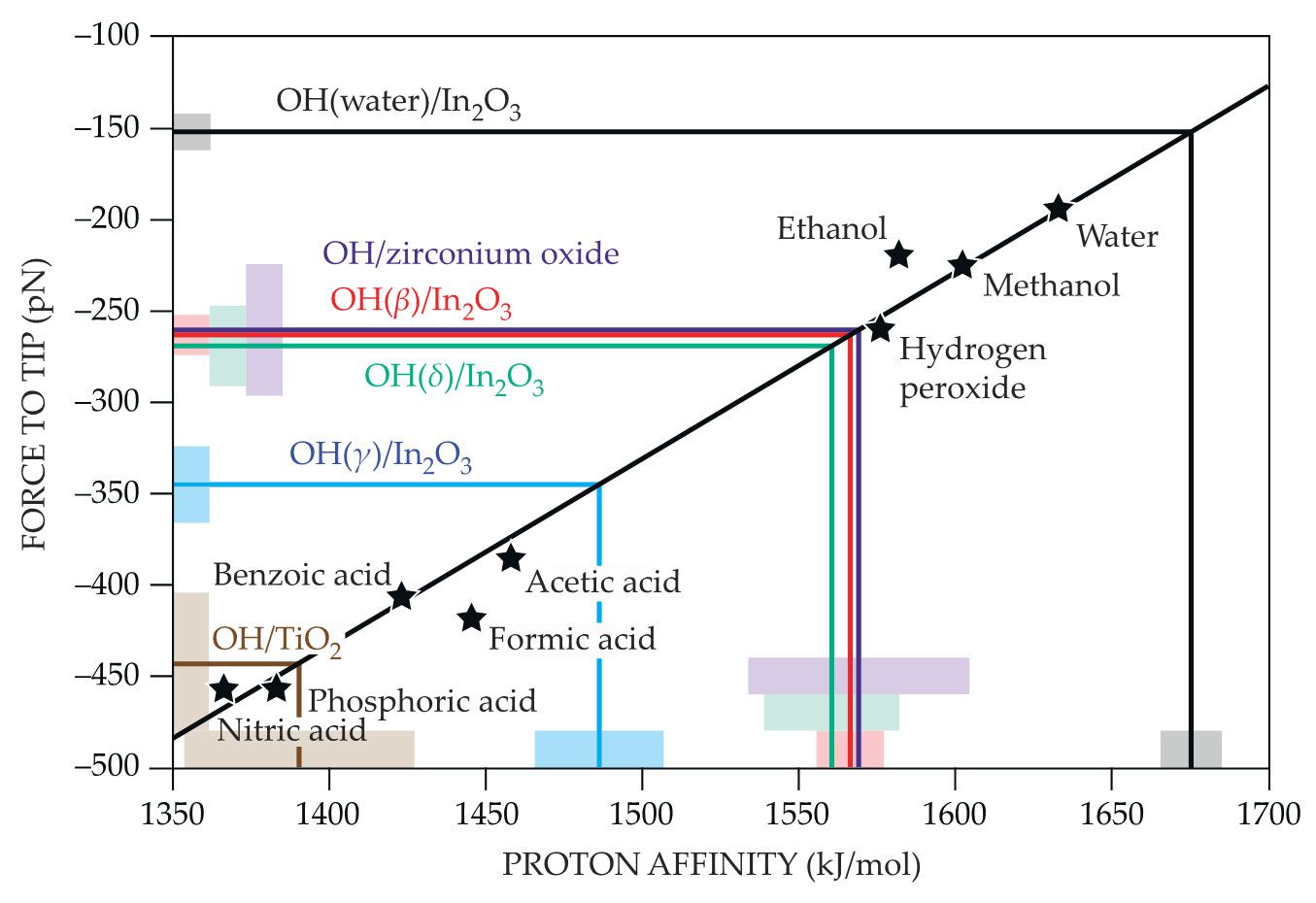

To relate the AFM force measurements to conventional notions of acidity, Meyer had the idea to calculate the force between the model tip and the H atoms of a suite of small molecules whose acidities are known. From those calculations, he derived a linear calibration, shown in figure

Figure 2.

The quantitative relationship between proton affinity and atomic-force-microscopy (AFM) forces is derived from a series of density functional theory calculations on molecules of known acidity (black stars). The best-fit calibration line can then be used to convert measured AFM forces to proton affinities for surface sites. So far, proton affinities have been found for three oxygen sites on indium oxide (red, green, and blue), water adsorbed on indium oxide (black), and oxygen sites on zirconium oxide (purple) and titanium dioxide (brown). The shaded blocks represent the surface measurements’ error bars. (Adapted from ref.

The calibration line makes it possible to convert the measured AFM forces on a surface to proton affinities for each surface site. The water OH site, as plotted in black, is the least acidic site on the In2O3 surface; the γ site, as plotted in blue, is the most. Using the same In2O3 AFM tips, the researchers have begun extending their measurements to other surfaces, including titanium dioxide (brown) and zirconium oxide (purple).

So far they’ve studied only regular surfaces with just one or a few types of surface O sites. Eventually, though, they want to look at surfaces with steps, defects, and impurities to see how those features affect surface chemistry. “The next big open challenge,” says Diebold, “is to do all the same measurements in liquid water.”

References

1. M. Wagner et al., Nature 592, 722 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03432-3

2. M. Wagner et al., ACS Nano 11, 11531 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b06387

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org