A geophysicist uses Swifties’ seismic activity for science outreach

DOI: 10.1063/pt.xgpn.pyku

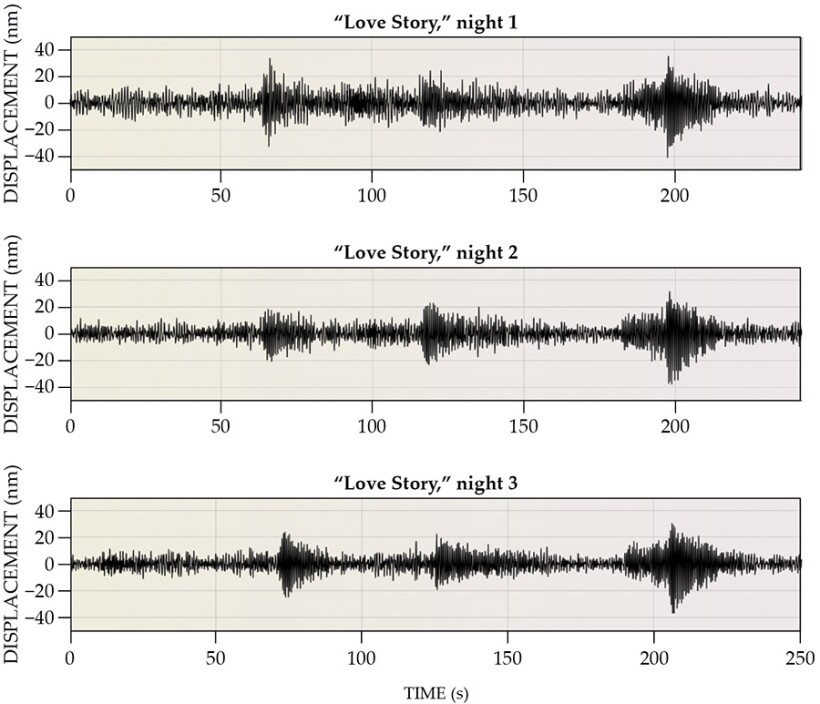

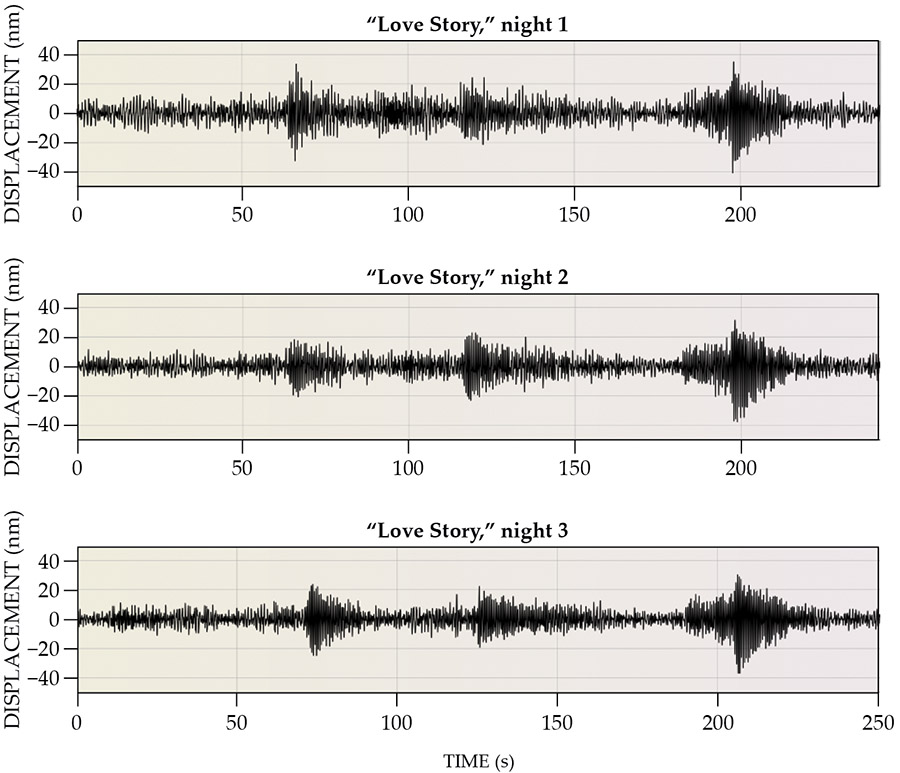

For each of Taylor Swift’s three Dublin concerts in June 2024, the ballad “Love Story” produced the most seismic energy out of all the songs performed. A seismometer 53 meters from the stadium recorded peak activity during the chorus of the song. (Image courtesy of Eleanor Dunn.)

As many fans jumped and sang along with their idol at a Dublin concert at Aviva Stadium last June, one stayed outside the venue and quietly took data. Eleanor Dunn had set up 41 seismometers at 21 locations near the stadium where Taylor Swift would be performing for three nights. Residents let her put the seismometers inside their homes and underground on their property. Dubbed #SwiftQuakeDublin on social media, the research project by Dunn and her supervisor was designed to quantify the ground vibrations triggered by Swift’s concerts and to educate the public on the diverse sources of seismic activity.

Eleanor Dunn, a PhD candidate in geophysics and science communication at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. (Photo courtesy of Eleanor Dunn.)

The fourth-year PhD candidate in geophysics at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies primarily researches the Sierra Negra, a volcano in the Galápagos Islands that experiences significant seismic activity before eruption. But Dunn is also interested in science communication and the influence of celebrities on piquing public interest in science. In July 2023, a Taylor Swift concert in Seattle, Washington, made news when seismologists announced that the crowd’s movement registered activity equivalent to a magnitude 2.3 earthquake. As more concerts produced their own seismic activity, people online dubbed them Swift Quakes.

Leading up to the Dublin concerts, Dunn launched social media accounts on TikTok, Instagram, and X to promote her research. Dunn noticed that many people were worried about a potential earthquake because “Swift Quake” was in her project’s hashtag. “People thought fans were encouraged to cause mass destruction,” she says. But “seismic activity happens when you jump up and down in a room, and it doesn’t cause damage.” She aimed to show that seismic activity occurs every day, usually from sources such as transportation and construction but occasionally from major sporting and entertainment events, and even in places like Ireland that don’t commonly experience earthquakes.

Every night during the three concerts, Dunn sat 25 meters away from the stadium and recorded the time each song began. Her subsequent analysis of the seismic data showed that all the songs were easily detectable from a seismic station 14 kilometers away. One song, “Shake It Off,” registered 113 kilometers from the venue. It has a repetitive beat that is easy to dance to, Dunn says, which is likely why the song had such an impact. The popular ballad “Love Story” produced the most seismic energy during each of Swift’s performances.

Seismometers measured the ground vibrations produced from three Taylor Swift concerts in Dublin in June 2024. (Photo courtesy of Eleanor Dunn.)

Dunn also wanted to elicit fans’ interest in the research by involving them. She asked concert attendees to send her videos from the concert so she could compare stadium activity with the seismic data. She received 211 videos that covered almost every song.

Dunn plans to publish two papers: one based on the data and another about the science communication aspects of the campaign. “Social media is impossible to ignore now,” she says. “You have to be on social media if you are a science communicator.”

Science communication is all about “understanding who you are talking to and what they want to take away from the conversation,” says Dunn. “It requires different tactics for different groups.”

This article was originally published online on 23 January 2025.