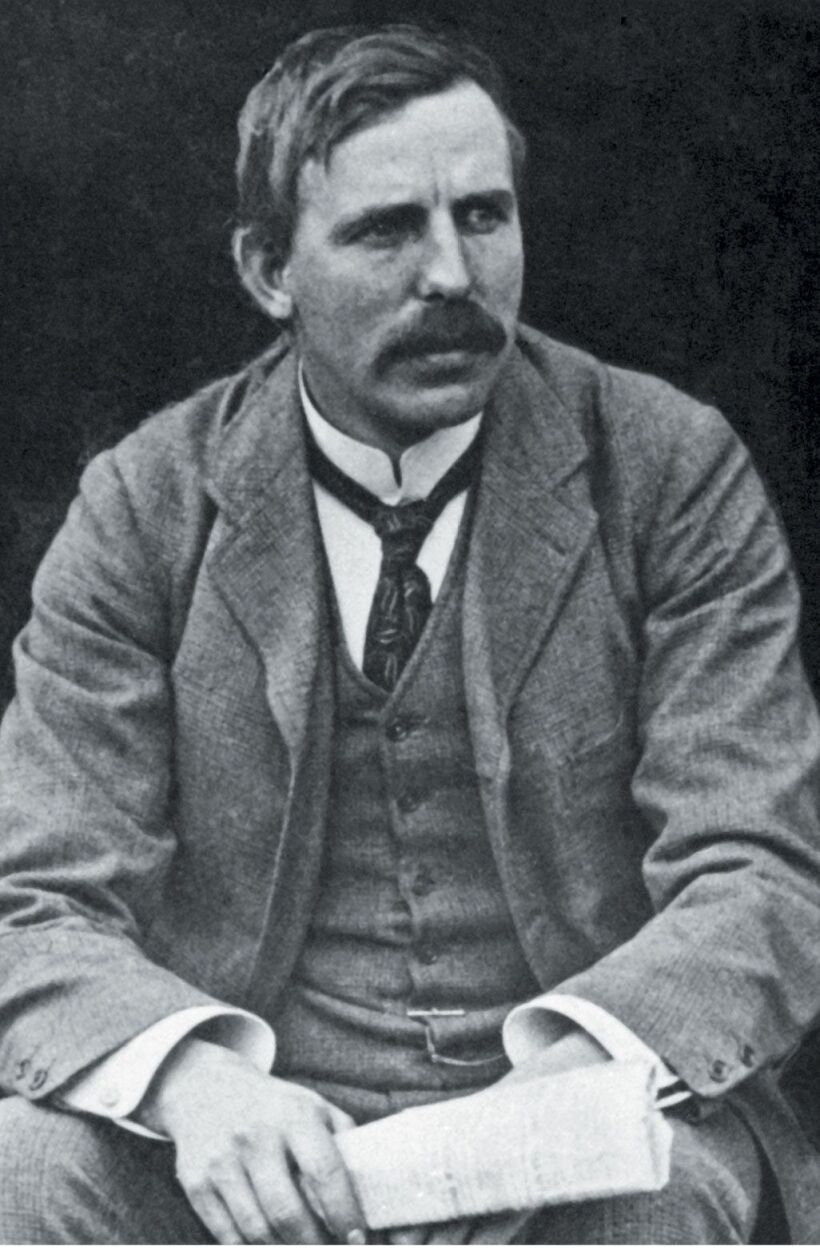

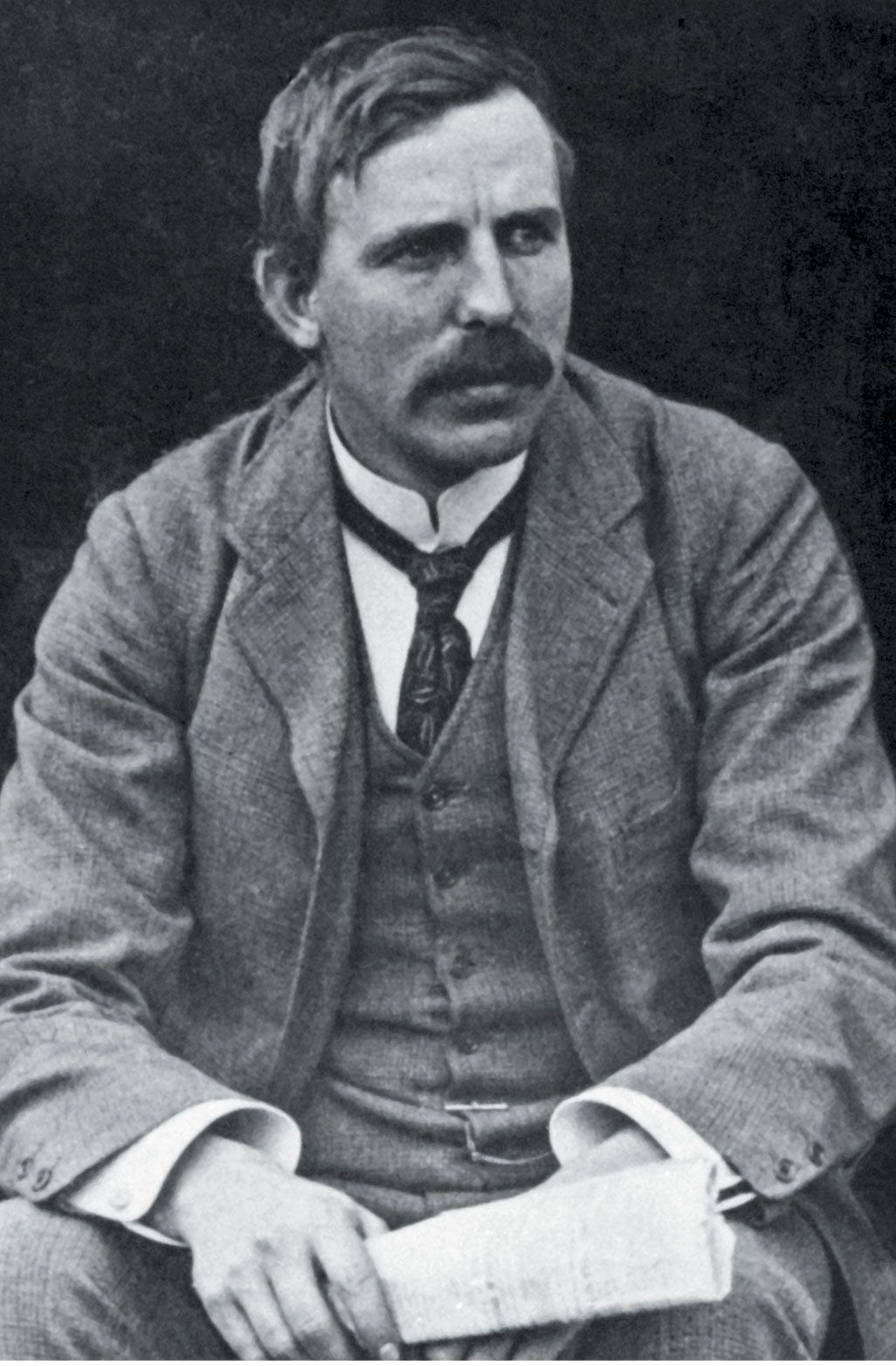

Some remarks about Rutherford

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4971

I read with interest Melinda Baldwin’s article on Ernest Rutherford’s publication strategies in relation to the journal Nature (Physics Today, May 2021, page 26

Ernest Rutherford did not make North American journals a major part of his publishing plans, but his discoveries may have motivated the Royal Society of Canada to create a rapid-publication mechanism. (Courtesy of the AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, gift of Otto Hahn and Lawrence Badash.)

But there is more to the story. The discoveries of Rutherford and his colleague John McLennan, who was then also working on radioactivity at the University of Toronto, may have had a part in the creation of a means of rapid publication for the Royal Society of Canada (RSC).

Rutherford was elected a member of the RSC in 1900, and at the June 1904 meeting he was elected president of the RSC’s section 3, devoted to mathematical, physical, and chemical sciences. As a section officer, Rutherford was a member of the RSC Council. In its annual report presented during the May 1905 general meeting, the RSC Council raised a problem related to the publication of the society’s Transactions. The members pointed out that it was difficult to quickly publish a volume containing pieces from very different disciplines. In addition to Rutherford’s section, the RSC also had members in the fields of biology and geology (section 4) and the humanities (sections 1 and 2). Though delays did not bother those in the humanities, it sometimes created problems for scientists.

The report insisted that “delay in the announcement of a scientific discovery may be very serious to original investigators, and, therefore, papers embodying important original results will not be sent to our volume of Transactions for publication” (reference , page II). Referring implicitly to Rutherford and McLennan’s work on radioactivity, the report added the following:

The revolution in scientific thought now in progress is fundamental, and some of our members are in the van of the movement. Conceptions of the constitution of matter which have been held for ages are now yielding to theories radically different, and laws established, even in recent times, are being profoundly affected. Under such conditions, and they have arisen very suddenly and recently, it might be well to inquire whether it would not be advisable to meet the emergency by issuing a bulletin…. In this way priority of discovery can be secured, and separate papers might be issued from the bulletin type. (reference

1 , page II)

A committee, consisting of members of sections 2, 3, and 4, earlier had been formed to consider the idea of the bulletin. Presenting their report at the same 1905 meeting, they recommended a mechanism that would allow papers worthy of immediate publication, as judged by the secretary of the appropriate section, to be immediately printed. The author would receive a limited number of copies, which he could then distribute. Rutherford was absent, but Alexander Johnson, president of the society, moved the adoption of the report. McLennan seconded the motion, which was carried (reference , page XIII).

The first such bulletin was printed in June 1907. It contained two studies— one on radium and another on its emanation—that were carried out under Rutherford’s direction. Notably, it appeared one month after Rutherford’s departure for the University of Manchester in the UK. McLennan and William Kennedy’s paper “On the radioactivity of potassium and other alkali metals” was later published in bulletin form as well.

So, even though “North American journals did not play a large role in Rutherford’s publishing strategy,” as Baldwin rightly notes, Rutherford nonetheless contributed to raising his colleagues’ consciousness about the importance of rapid publication. 2 That led to improvement in the Canadian publication system, which then better served his Canadian colleagues and former students.

References

1. Council of the Royal Society of Canada, in Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, 2nd ser., vol. 11 (1906).

2. For additional detail, see Y. Gingras, Physics and the Rise of Scientific Research in Canada, P. Keating, trans., McGill-Queen’s University Press (1991), p. 86.

More about the authors

Yves Gingras, (gingras.yves@uqam.ca), University of Quebec in Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.