Solid-state NMR in biological and materials physics

DOI: 10.1063/1.3226855

Detection of nuclear magnetic resonance signals from condensed matter was first reported in 1946. 1 , 2 Applications of NMR to probe the properties of matter have expanded ever since, from solid-state physics and chemistry in the 1950s, to biochemistry and biology in the 1960s, to medicine in the 1970s with the advent of magnetic resonance imaging. By now, nearly every area of the natural sciences has felt the impact of NMR measurements, and even applications in various branches of psychology have become prevalent. As NMR’s use has spread, the information content of NMR measurements has increased in each discipline through a steady stream of methodological and technological advances.

This article focuses on solid-state NMR spectroscopy, meaning NMR applied to solids or to materials that are solidlike in the sense that the internal molecular and atomic motions are highly restricted compared with the motions in isotropic liquids. Those motions profoundly affect NMR signals. The isotropic tumbling of molecules in solution averages out nuclear spin interactions that depend on molecular orientation and results in comparatively simple NMR spectra with sharp lines. Without that motion, orientation-dependent interactions make for much more complex spectra. Extraction of useful information from solid-state NMR spectra therefore requires that the nuclear spin interactions be manipulated in sophisticated ways to simplify the spectra.

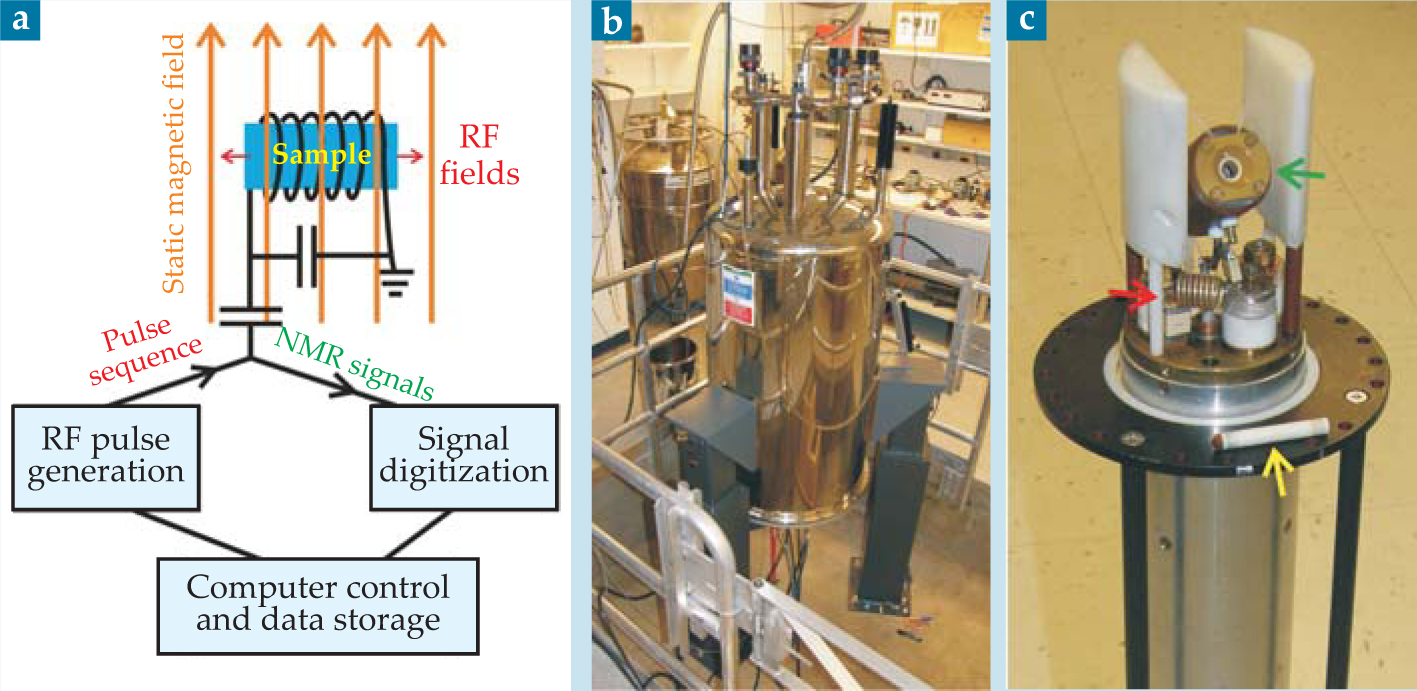

The experimental setup for a basic NMR measurement is shown in figure 1. A sample sits in a strong static magnetic field, typically 10–20 T, which slightly polarizes the spins of magnetic nuclei to produce a bulk nuclear magnetization aligned with the field. A coil around the sample is used to apply an RF pulse or sequence of pulses with photon energies near the nuclear spin-flip energies—typically 10–1000 MHz, or 40–4000 neV. In general, the RF pulses perturb the nuclear spin polarization to produce a transverse magnetization, which precesses about the static field at NMR frequencies corresponding to the spin-flip energies. The precessing magnetization induces a voltage in the coil, and Fourier transformation of that time-dependent signal (called the free-induction decay) produces a spectrum of all the NMR frequencies.

Figure 1. (a) Typical setup for a nuclear magnetic resonance measurement. The sample sits in the coil of a circuit tuned to the nuclear spin-flip energy. RF pulses produce fields in the coil that perturb the nuclear spins and generate NMR signals. Pulse-sequence timing and signal digitization are under computer control. (b) A superconducting NMR magnet in a research lab. (c) A solidstate NMR probe for magic-angle spinning experiments. Samples are loaded into cylindrical rotors (yellow arrow), which spin rapidly in the pneumatic MAS assembly (green arrow). Components of the RF circuit (red arrow) are also visible.

An NMR spectrum is specific to a single magnetic isotope, often one with spin ½. For isotopes with low natural abundance, such as carbon-13 or oxygen-17, one can specially prepare samples with isotopic labels at sites of interest. The NMR frequencies for a given isotope all fall within a narrow range and are presented as parts-per-million shifts from a standard value for that isotope. The shifts reflect differences in the local magnetic field felt by each nucleus and provide information about the structural properties of the sample.

Interactions that influence NMR frequencies include chemical shifts, dipole–dipole couplings, electric quadrupole couplings, and hyperfine couplings. Chemical shifts are caused by the circulation of electrons in the magnetic field to produce an opposing field; they provide information about local electronic structure and chemical bonding. Dipoledipole couplings occur between pairs of nearby magnetic nuclei and reflect interatomic distances and directions.

Electric quadrupole couplings reflect charge distributions about the nuclei, and hyperfine couplings reflect interactions with unpaired electrons. Furthermore, dynamical information is available from NMR measurements that probe the interactions’ time-dependent fluctuations, which result from structural fluctuations.

Even in a simple measurement, NMR signals are usually determined by several interactions acting simultaneously, and the resulting spectrum can be difficult to deconvolve and interpret. But suitably designed RF pulse sequences and rapid sample rotation can manipulate the nuclear spin interactions to produce an effective nuclear spin Hamiltonian in which, for example, only one interaction remains. Two-dimensional and higher-dimensional NMR techniques can separate the effects of different interactions into separate time periods, which become separate frequency dimensions after Fourier transformation. With those modern approaches, individual nuclear spin interactions and the information they contain can be exposed in clearly interpretable ways. Explorations of new applications, often involving new spectroscopic properties, drive the invention and refinement of solid-state NMR techniques.

Proteins, peptides, and amyloid fibrils

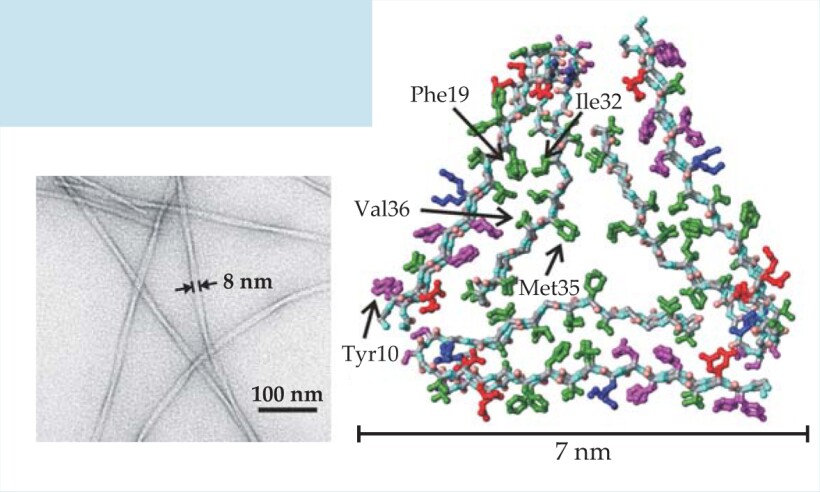

Polypeptides are linear-chain polymers formed from amino acid monomers; they include long-chain proteins and shorter-chain peptides. A polypeptide’s structure is normally determined uniquely by its amino acid sequence and stabilized by specific interactions among the amino acids. However, polypeptides often have alternative structural states, called amyloid fibrils, in which many copies of the chain assemble into filaments, typically 5–10 nm in diameter and a few microns in length. Surprisingly, amyloid formation does not strongly depend on amino acid sequence. Amyloid fibrils are implicated in a variety of human diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, in which they form plaques in the brain, and type 2 diabetes, in which they develop in the pancreas. In each amyloid disease, the fibrils are formed by a different polypeptide, develop in the affected tissue, and contribute to cell death by mechanisms that are not entirely known.

Detailed knowledge of the molecular structures of amyloid fibrils would help explain why amyloid formation is a common property of polypeptides and would facilitate drug development. Although the inherently noncrystalline and insoluble nature of amyloid fibrils makes structure determination difficult, substantial progress has now been made using solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. The figure on the left is an electron microscope image of one type of amyloid fibril, formed by the 40-amino-acid β-amyloid peptide, or Aβ40. It is a major component of senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. On the right is a molecular structural model developed from solid-state NMR data. Green, magenta, red, and blue indicate, respectively, hydrophobic, polar, negatively charged, and positively charged amino acid sidechains. The first eight amino acids of Aβ40 are disordered in the fibrils, so they are not included in the model.

(Figure adapted from ref. 12.)

New materials for batteries and fuel cells

The need to convert and store energy from renewable sources drives the search for materials that will increase the efficiency and reduce the cost of fuel cells and batteries. (See the article by Héctor D. Abruña, Yasuyuki Kiya, and Jay C. Henderson, Physics Today, December 2008, page 43

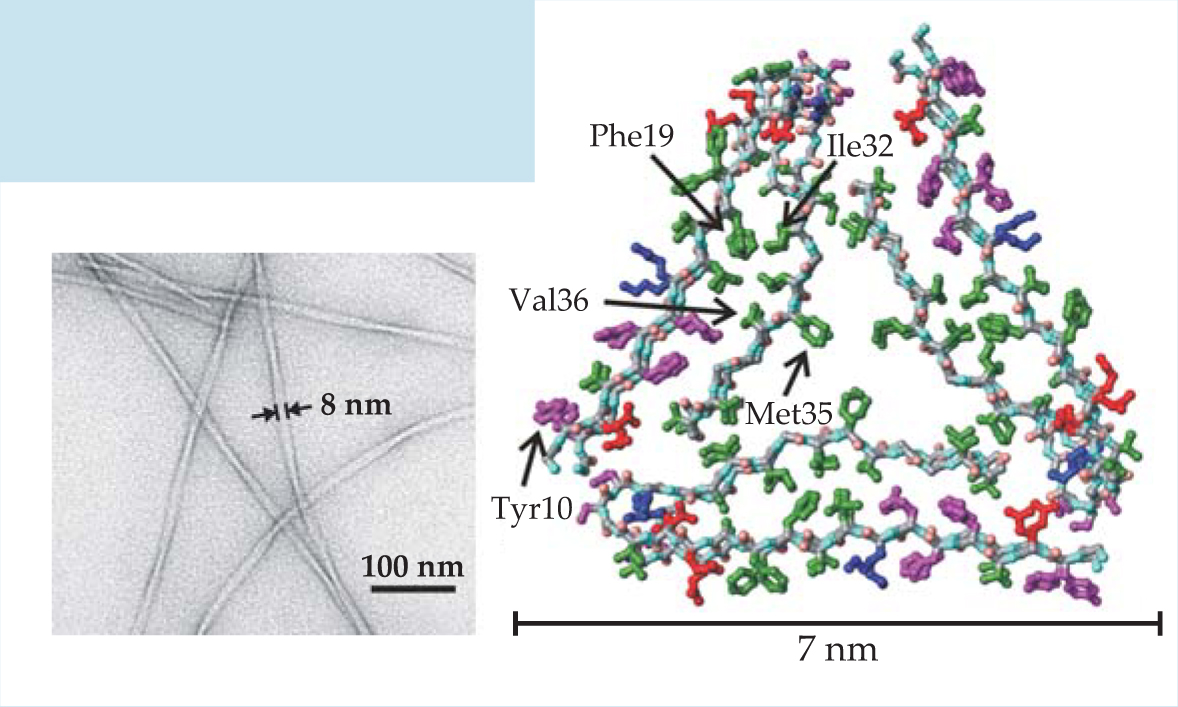

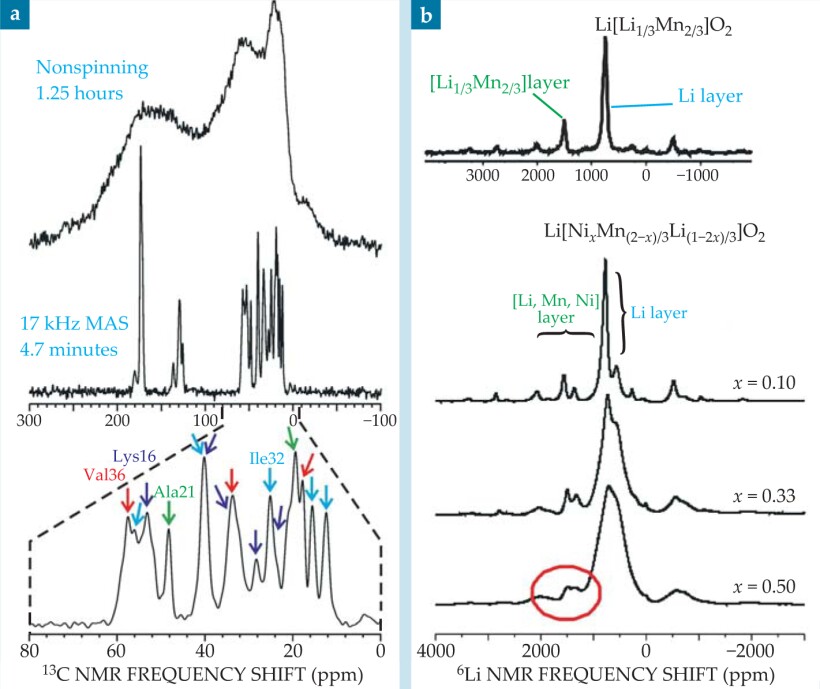

One way to achieve higher battery capacities is to use electrode materials whose oxidation and reduction processes involve more than one electron per atom. For example, in cathode materials with composition between Li2MnO3 and Li(NiMn)0.5O2—that is, Li[NixMn(2-x)/3Li(1-2x)/3]O2—the Ni 2+ ions are oxidized to Ni 4+ when the battery is fully charged. such materials have attracted considerable interest. The end member, Li2MnO3, comprises layers of Li+ ions interspersed with layers of [Li1/3Mn2/3]3+ in which Li+ and Mn4+ form a honeycomb lattice, as shown in the figure, that minimizes Mn4+−Mn4+ repulsions. NMR spectra of the Ni 2+−substituted materials are similar to that of Li2MnO3, as shown in figure 2(b), and indicate that the honeycomb ordering persists in those compounds. For the x = 0.5 member, the ordering is associated with Ni 2+–Li+ exchange between the different cation layers; without such an exchange, there would be no Li+ in the transition-metal layer.

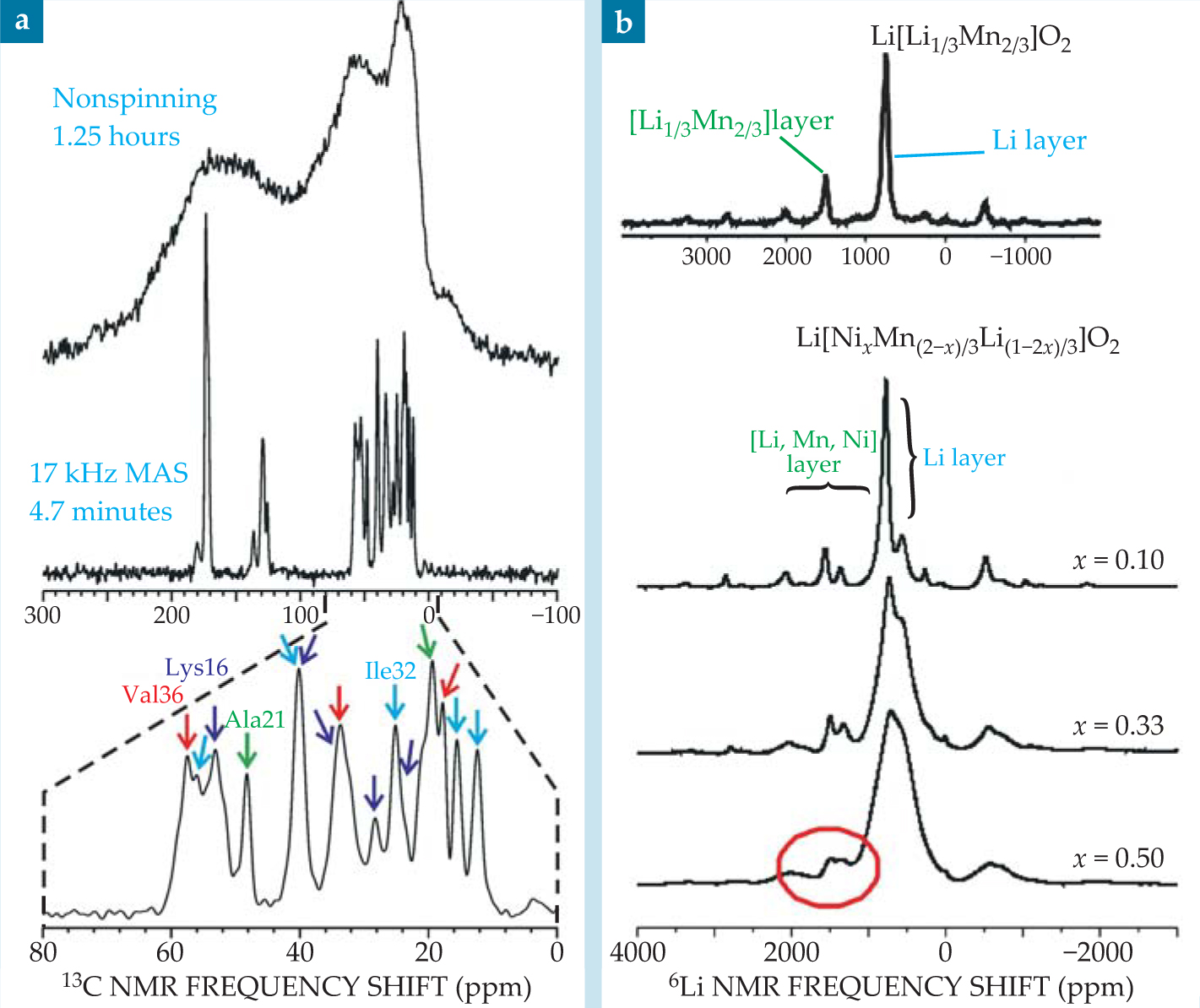

Figure 2. (a) The effect of magic-angle spinning on the carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of Aβ40 fibrils, a polypeptide structure connected with Alzheimer’s disease. The sample was prepared with 13C labeling of all carbon sites in six amino acids (Lys16, Phe19, Ala21, Glu22, Ile32, and Val36). MAS at 17 kHz dramatically enhances the resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, so that the spectral lines can be resolved and assigned to specific carbon sites. (b) Lithium-6 NMR spectra of Li[Ni x Mn(2-x)/3Li(1-2x)/3)]O2, a family of materials that are candidates for battery cathodes. MAS allows signals from Li sites in Li+ layers and in transition-metal layers to be resolved. The peak circled in red arises from Ni2+–Li+ exchange between the layers, a structural defect that limits the material’s performance as a cathode material.

(Adapted from W.-S. Yoon et al.,

The ability to resolve different local environments by solid-state NMR allows spectroscopists to determine which Li+ ions are removed at different states of charge. Lithium-6 NMR spectra show that when a battery containing Li[NixMn(2-x)/3Li(1-2x)/3]O2 electrodes is charged, Li+ ions are removed from both the Li and transition-metal layers. The resulting vacancies in the transition-metal layers allow significant structural rearrangements to occur, so that the material obtained after multiple charge cycles is very different from the starting material. That finding has contributed to the development of a new material with the ideal layered structure Li[Ni1/2Mn1/2]O2, containing no Ni 2+ ions in the Li+ layers. Electrodes made of that material have significantly higher rate performance: The battery’s capacity is preserved even after discharging in less than 15 minutes. 6

Magic-angle spinning

In solid samples whose molecules or crystallites are randomly oriented, orientation-dependent interactions, such as dipole–dipole couplings and the anisotropic parts of chemical shifts, lead to NMR spectra with broad peaks (really, dense forests of unresolved lines) that provide little information, or information that is difficult to deconvolve, as shown in the top portion of figure

Figure

MAS is also a boon to studies of technologically important materials that are disordered or amorphous and whose structures cannot be fully understood from diffraction data alone. For example, figure 2(b) shows lithium-6 NMR spectra of Li[Ni x Mn(2-x)/3Li(1-2x)/3]O2, a family of layered materials with potential applications in lithium-ion batteries, as described in

Pulse sequences and average Hamiltonian theory

Nuclear spin interactions can also be manipulated by RF pulse sequences, as explained in the formalism of average Hamiltonian theory.

7

The idea of AHT is as follows: When the total spin Hamiltonian contains interactions with time-dependent RF fields H RF (t) and internal interactions H int, and if the RF interactions are stronger than the internal interactions, then it makes sense to separate the two terms by transforming into a new frame of reference, or interaction picture, in which the RF interactions vanish. In the new frame, the internal interactions are given by

The average Hamiltonian depends on both H int and the RF pulse sequence. If, for example, H int is the sum of two terms that respond differently to the rotations of spin angular momenta produced by RF pulses, then it may be possible to selectively remove one of the two terms from

The concept of manipulating internal interactions with external radiation is not unique to NMR. But it certainly has achieved its greatest expression in NMR, because of the ease of operating in the limit in which the interactions with applied pulses are stronger than internal interactions, and because the technology for generating RF pulse sequences of arbitrary complexity with precisely controlled amplitudes, phases, and timing is well developed.

Recoupling: Combining MAS with AHT

The line-narrowing of MAS is often essential to solid-state NMR, but it is achieved at the expense of information contained in the orientation-dependent nuclear spin interactions. In particular, dipole–dipole couplings contain information about internuclear distances and directions, and chemical-shift anisotropies contain information about chemical bonds, molecular orbitals, and orientations of chemical groups. But one can recover that information by applying MAS in synchrony with a pulse sequence whose period τp is a multiple of the sample rotation period. Such so-called recoupling sequences work by introducing an additional time dependence that interferes with the one caused by MAS, so that even if the average of H int (t) is zero under MAS alone, the average of

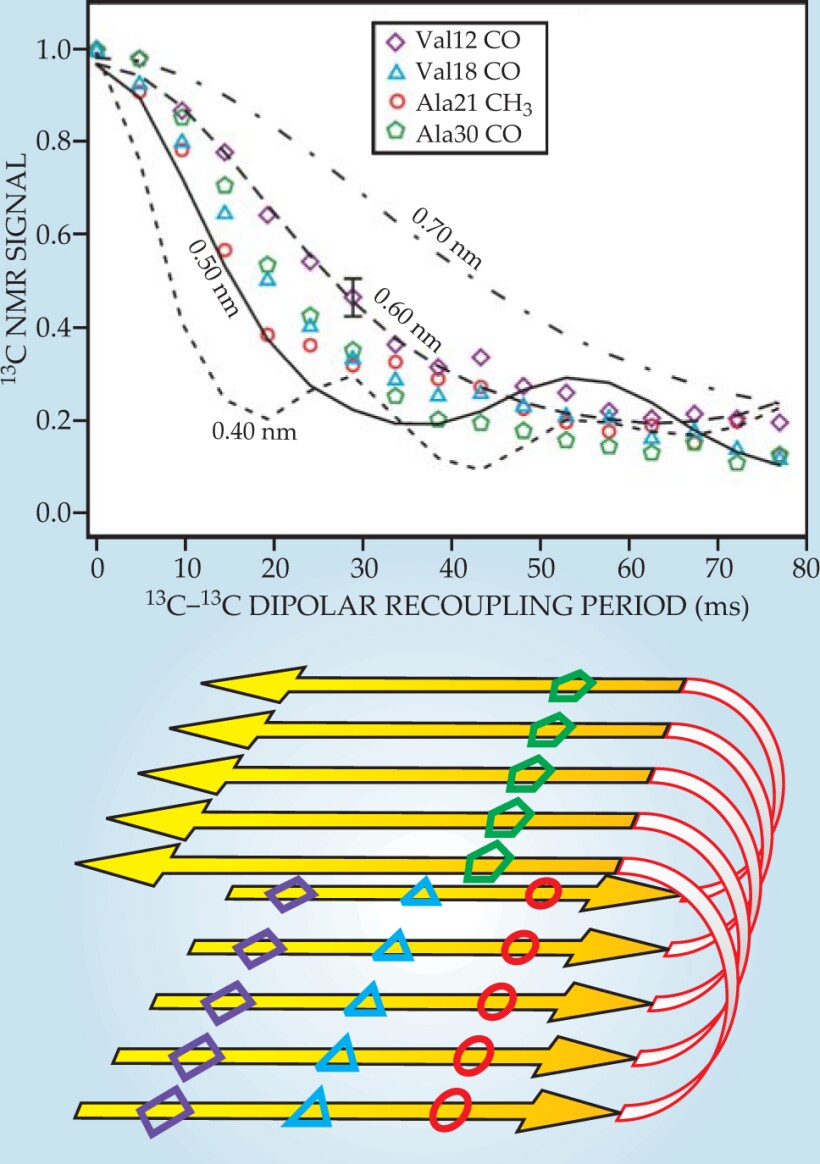

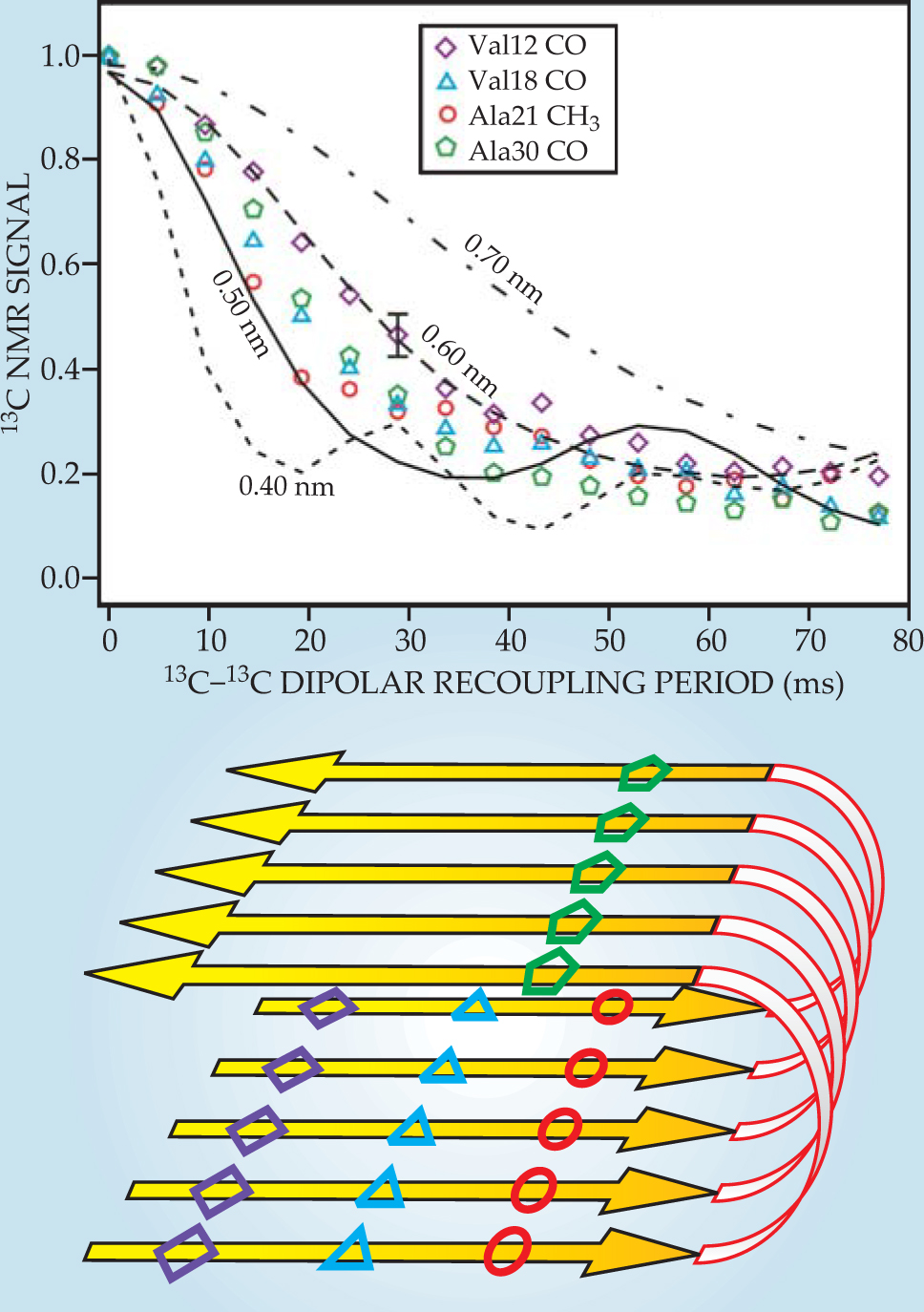

Figure 3 shows dipolar recoupling data for Aβ40 fibrils prepared with one 13C label in each Aβ40 molecule. The 13C-13C dipole–dipole couplings therefore depend on intermolecular distances within the fibrils. Comparisons with numerical simulations show that those distances are approximately 0.5 nm, which is what is expected if Aβ40 molecules align with their neighbors to form parallel β sheets, or ribbonlike structures, within the fibrils. By instead preparing each Aβ40 molecule with two or more isotopic labels, one can obtain dipolar recoupling data that provide information about the conformation of individual Aβ40 molecules. 3 , 11 , 12

Figure 3. Carbon-13 dipolar recoupling data for Aβ40 fibrils prepared with 13C labels at carbonyl (CO) or methyl (CH3) carbon sites of specific amino acids. Comparing the signal decays (colored symbols) to numerical simulations (black lines) provides a measurment of intermolecular distances, which ae all found to be approximately 0.5 nm. The data indicate that the Aβ40 molecules from parallel β sheets within the fibrils, as shown schematically in the lower panel.

(Adapted from ref. 12.)

Multidimensional spectroscopy

Multidimensional NMR spectroscopy, in which the NMR signal is plotted as a function of two or more frequency variables, is a flexible concept. Depending on the sample, its spin system, and how the spectrum is acquired, multidimensional spectra can serve many purposes. They can provide additional constraints on molecular structure, aid in the interpretation of a 1D spectrum, or provide information about time-dependent processes within the sample.

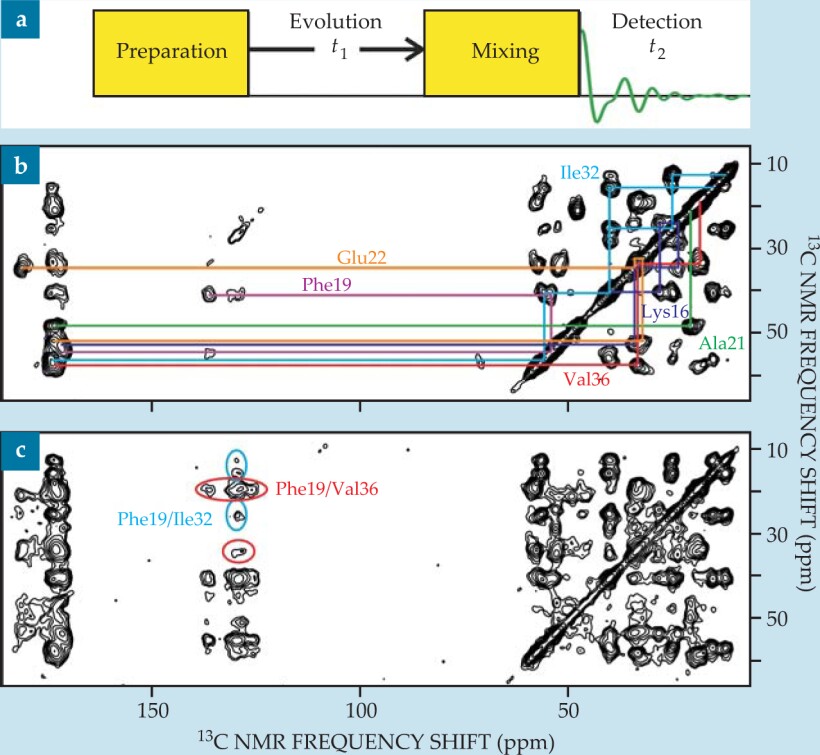

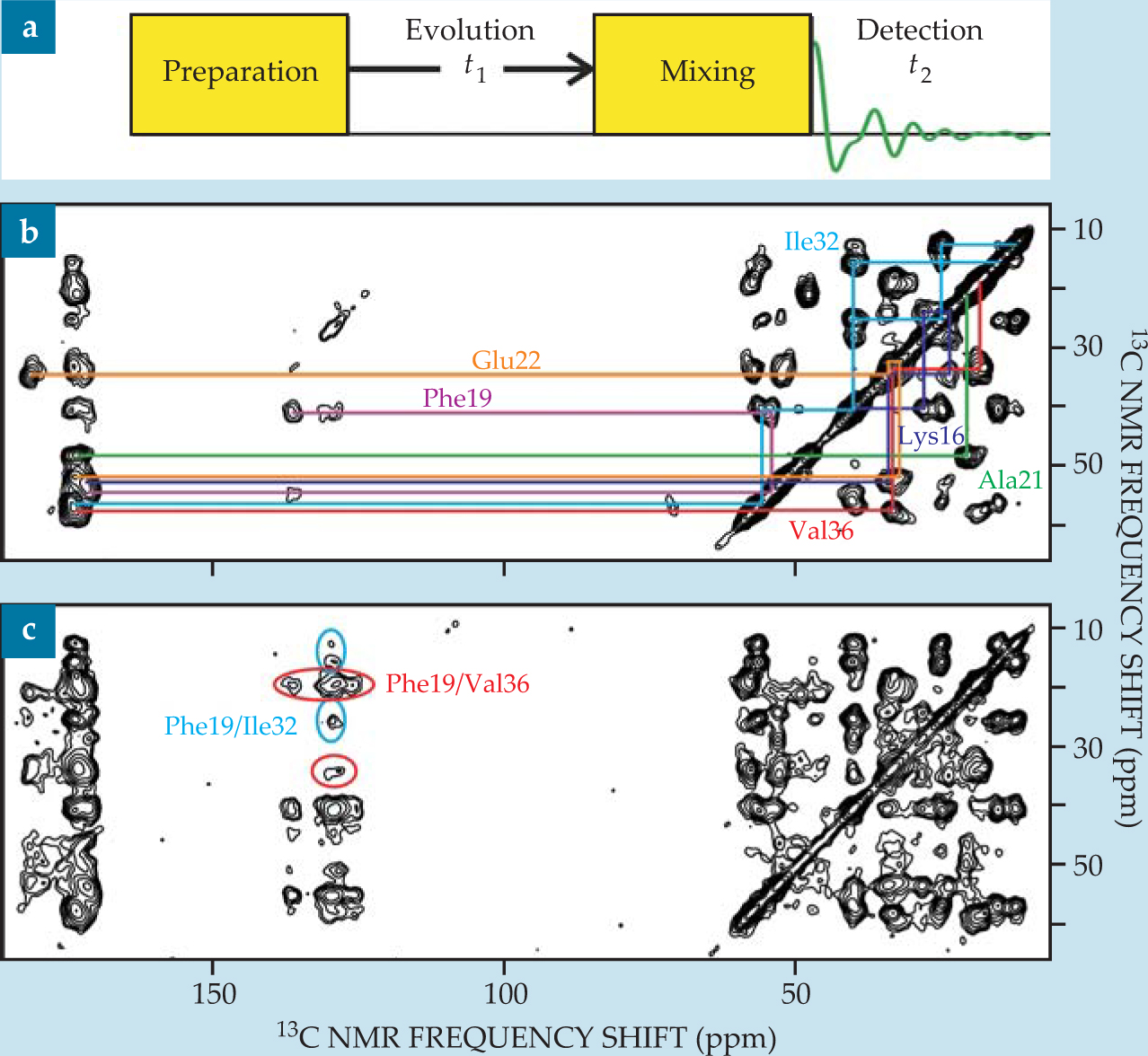

A 2D NMR spectrum is obtained using RF pulse sequences divided into four periods, called preparation, evolution (or t 1), mixing, and detection (or t 2), as shown in figure 4(a). The preparation and mixing periods have fixed durations and pulse structures. Free-induction decay signals are recorded during the detection period as a function of t 2, and the process is repeated for many values of t 1. The full data set, a function of two time variables, is Fourier transformed to yield a spectrum that is a function of two frequency variables. Higher-dimensional spectra are obtained by introducing additional evolution and mixing periods.

Figure 4. (a) Two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance measurements take a general form. Signals are recorded during the t 2 period, and t 1 is varied between successive scans. (b) A 2D carbon-13 NMR spectrum of Aβ40 fibrils (the same sample as in figure

Resonance assignments and structural constraints. If, during the mixing period, spin polarization is transferred between nuclei with NMR frequencies ω a and ω b , then the 2D spectrum exhibits off-diagonal peaks, or cross peaks, connecting ω a and ω b . By constructing the mixing period so that only pairs of nearby nuclei can exchange polarization—for example, by applying a dipolar recoupling sequence for a relatively short time—one obtains a pattern of cross peaks that facilitates the assignment of the NMR frequencies to specific atoms, as shown in figure

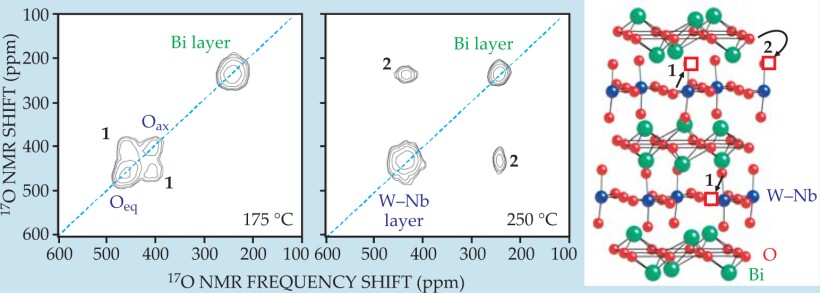

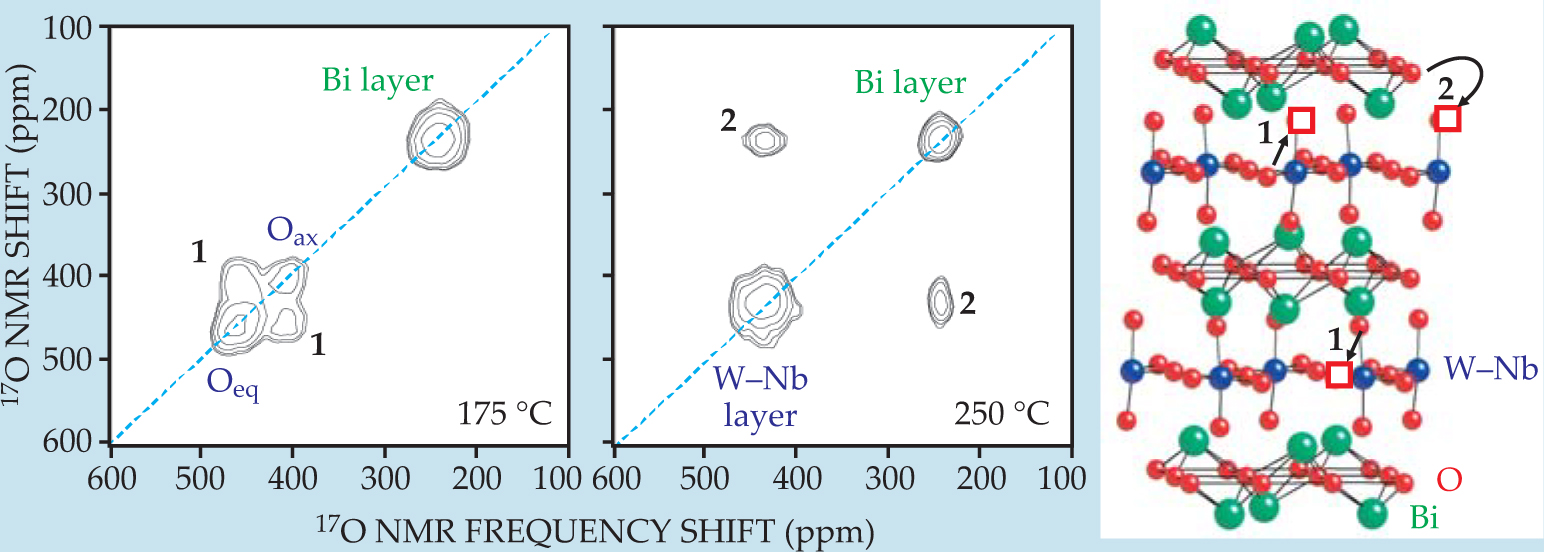

Internal motions. If, during the mixing period, atoms move between inequivalent sites in a crystal or molecules change their conformation, then NMR frequencies associated with those atoms or molecules can change significantly between the t 1 and t 2 periods—another source of cross peaks in the 2D spectrum. The cross peaks’ frequencies, amplitudes, and temperature dependencies provide information about the mechanisms and kinetics of the internal motion that produced them. For example, figure 5 shows 2D 17O NMR spectra of niobium-doped Bi2WO6. Two different types of oxideion migration are revealed, with the faster one occurring within the tungsten–niobium layers and the slower one occurring between the W–Nb layers and the bismuth layers. 13 Similar experiments can be used to probe molecular motions in biological materials.

Figure 5. Two-dimensional oxygen-17 nuclear magnetic resonance spectra and structure of Bi2W0.9Nb0.1O5.95, with oxide vacancies indicated by red squares. The material is a candidate for use in membranes for separating oxygen and nitrogen, since oxide ions O2- can migrate through it but N atoms or ions cannot. At 175 °C, atomic motion on the 5-ms time scale of the mixing period only involves hops between the two oxide environments in the tungsten–niobium layers. That motion (process 1) produces cross peaks between the 17O resonances of axial (Oax) and equatorial (Oeq) oxide ions. At 250 °C, process 1 is so fast that the axial and equatorial 17O frequencies average to a single value. Process 2, involving hops between the bismuth and W–Nb layers, produces cross peaks between those environments’ resonances.

(Adapted from ref. 13.)

Additional applications and future directions

The power and flexibility of solid-state NMR ensures that its uses will continue to expand. Well-established applications in materials physics—such as characterization of heterogeneous catalysts, glasses, and polymers—and some of the newer applications described above will be increasingly performed in situ, so that materials properties can be probed under conditions that closely mimic those of the real devices or processes. In biological systems, solid-state NMR is now being applied to integral membrane proteins that function as hormone receptors, ion channels, and energy transducers. Systems being explored include intact viruses and viral components, bacterial cell walls, proteins involved in biomineralization, and unfolded states of proteins. As exemplified by studies of amyloid fibrils, results from solid-state NMR not only contribute to the basic understanding of molecular biophysics but can also have important biomedical implications.

Our discussion of solid-state NMR techniques is far from exhaustive. For materials applications, novel techniques for obtaining high-resolution NMR spectra of nuclei with spins greater than 1/2, such as aluminum-27, oxygen-17, boron-11, and sodium-23, are especially important. 14 Those techniques overcome the severe line-broadening induced by electric quadrupole couplings (which are averaged out to first order by MAS, but for which second-order effects can produce widths of 10 kHz or larger) and have proven to be especially valuable in studies of zeolite catalysts, organic electronic materials, inorganic glasses, and ceramics.

Structural studies of proteins embedded in biological membranes often employ techniques designed specifically for oriented systems, since the membranes can be oriented either magnetically or by deposition on planar substrates. 16 In oriented systems, nuclear spin interactions such as magnetic dipole–dipole couplings and anisotropic chemical shifts provide constraints on the directions of chemical bonds relative to the magnetic field. With enough of those constraints, full molecular structural models can be developed. Experiments on oriented systems exploit AHT and multidimensional spectroscopy, although usually not MAS.

Techniques for enhancing the sensitivity of solid-state NMR measurements are always important. In applications to biological systems, it is often difficult to prepare adequate quantities of isotopically labeled proteins or other biopolymers, and realistic samples often have inherently low concentrations. In situ studies of technologically relevant processes and studies of thin films are similarly restricted by sensitivity considerations. Recent progress in dynamic nuclear polarization—a phenomenon in which nuclear spin polarizations are greatly enhanced through interactions with electron spins 17 —and in low-temperature MAS technology 18 will encourage further expansion of the range of applications for solid-state NMR methods by making those methods applicable to nanomole and subnanomole sample quantities.

References

1. E. M. Purcell, H. C. Torrey, R. V. Pound, Phys. Rev. 69, 37 (1946). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.69.37

2. F. Bloch, W. W. Hansen, M. Packard, Phys. Rev. 69, 127 (1946). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.69.127

3. R. Tycko, Q. Rev. Biophys. 39, 1 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033583506004173

4. F. Chiti C. M. Dobson, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 333 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901

5. C. P. Grey N. Dupré, Chem. Rev. 104, 4493 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020734p

6. K. S. Kang et al., Science 311, 977 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1122152

7. U. Haeberlen J. S. Waugh, Phys. Rev. 175, 453 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.175.453

8. T. Gullion J. Schaefer, J. Magn. Reson. 81, 196 (1989).

9. R. Tycko G. Dabbagh, Chem. Phys. Lett. 173, 461 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(90)87235-J

10. M. A. Alla, E. I. Kundla, E. T. Lippmaa, JETP Lett. 27, 194 (1978).

11. T. L.S. Benzinger et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13407 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.23.13407

12. A. K. Paravastu et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18349 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0806270105

13. N. Kim, R.-N. Vannier, C. P. Grey, Chem. Mater. 17, 1952 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1021/cm048388a

14. A. Samoson, E. Lippmaa, A. Pines, Mol. Phys. 65, 1013 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1080/00268978800101571

15. A. Medek, J. S. Harwood, L. Frydman, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 12779 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00156a015

16. S. J. Opella F. M. Marassi, Chem. Rev. 104, 3587 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0304121

17. T. Maly et al., J. Chem. Phys. 128, 052211 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2833582

18. K. R. Thurber R. Tycko, J. Magn. Reson. 195, 179 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2008.09.015

More about the authors

Clare Grey is a professor of chemistry at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, New York, and at Cambridge University in Cambridge, UK. Robert Tycko is a senior investigator in the laboratory of chemical physics of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Clare P. Grey, 1 Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, US .

Robert Tycko, 2 National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, US .