Progress in superconductivity

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4138

One hundred years or so from now, humanity could be enjoying the benefits of room-temperature superconductivity with lossless transmission of electric currents and high-efficiency transport. A historian of physics of that time would undoubtedly be curious about how we came to fully comprehend the origins of that mysterious phenomenon in which dissipation-free motion of electrons in macroscopic systems is routinely achieved.

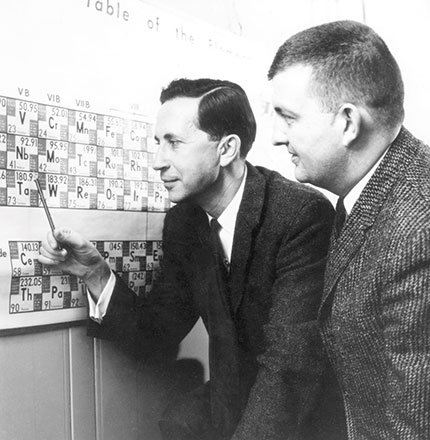

Bernd Matthias (1918–80) discovered hundreds of superconducting alloys and compounds. Here Matthias indicates niobium, a component of the superconducting compound Nb3Sn, which he discovered together with Ted Geballe in 1954. Also pictured is Eugene Kunzler, who used Nb3Sn to make the first high-field superconducting electromagnet. (Courtesy of the AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection, Berlincourt Collection.)

A natural place to start such a study would be with review papers that have been highly cited and were recognized in their day as providing thorough status reports and insightful suggestions for future research. Articles about superconductivity published in Reviews of Modern Physics (RMP) would certainly qualify. RMP is the world’s premier physics review journal with the highest impact factor. Many of its articles have garnered thousands of citations within 10 years of publication.

RMP reviews are rigorously refereed. By their very nature, they establish accepted timelines for the evolution of a field. The 1911 discovery of the zero-resistance state in distilled mercury by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes was a serendipitous event made possible by his 1908 landmark demonstration of liquefied helium. It wasn’t until 1933 that the expulsion of magnetic fields from a superconductor during its transition to the superconducting state—the Meissner–Ochsenfeld effect—was recognized, along with the earlier discovered zero resistance, to uniquely define the superconducting state. The ensuing phenomenological theory of superconductivity generated reviews of concepts critical to the development of high-field superconducting magnets 1 (work by Eugene Kunzler, shown in the photo, and others) and theories of flux-flow dissipation 2 associated with thermal activation of vortices (Alexei Abrikosov’s quantized flux lines) past or over pinning centers.

Phenomenological treatments of superconductivity converged with the trail-blazing publication of the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory, 3 which took into account the quantum mechanical nature of bound aligned pairs, or Cooper pairs, of interacting electrons embedded in a collective state of composite bosons. Because the bosons are immune to the influence of other electrons, charge moves without resistance. The analogous condensation of pairs of helium-3 atoms into superfluid phases of composite bosons has spawned a still incomplete but fascinating understanding of unconventional, non-BCS superconductivity in other materials—namely, in heavy-fermion systems 4 and high-Tc cuprates. 5 Multicomponent order parameters, 6 experimental schemes to determine order-parameter symmetry, 7 proximity coupling of superconductors to ferromagnets, 8 and the surprising occurrence of high-Tc superconductivity in the layered iron pnictides 9 , 10 all add to the breadth of phenomena associated with unconventional superconductivity.

As Bernd Matthias (

Our future historian of physics would certainly want to complement their survey of reviews of superconductivity by looking at compendia, collections, and tutorials from other sources. Such publications are not necessarily reviews. Rather, they identify in detail the highlights of a landscape from which reviews have already nucleated or might soon emerge. In that category, a particularly useful compendium on superconducting materials classes ranging from conventional to unconventional 13 presents a juxtaposition of 32 materials classes by 32 sets of authors with 32 unique perspectives and opinions.

In reporting to colleagues, our historian would carry the message that authors of RMP reviews of superconductivity had collectively acted like what might be called superconductors. Like a conductor in an orchestra pit, they tried to organize the fascinating and diverse phenomenology surrounding them. To recognize where the score is heading, it is necessary to identify the hot areas emerging from established reviews—for example, on topological superconductors 14 or graphene. 15 Specific recent examples might include the occurrence of interfacial superconductivity in two-dimensional crystalline materials 16 or the emergence of unexpected high-Tc superconducting phases at extreme pressures. 17 The ubiquity and promise of superconductivity in the worldly sphere discussed here and even out to the stars 18 guarantees that reviews on the subject area will not only monitor but will also be essential for progress.

References

1. C. P. Bean, Rev. Mod. Phys. 36, 31 (1964). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.36.31

2. P. W. Anderson, Y. B. Kim, Rev. Mod. Phys. 36, 39 (1964). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.36.39

3. J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, J. R. Schrieffer, Phys. Rev. 108, 1175 (1957). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175

4. G. R. Stewart, Rev. Mod. Phys. 56, 755 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.56.755

5. P. A. Lee, N. Nagaosa, X.-G. Wen, Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.78.17

6. M. Sigrist, K. Ueda, Rev. Mod. Phys. 63, 239 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.63.239

7. C. C. Tsuei, J. R. Kirtley, Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 969 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.72.969

8. A. I. Buzdin, Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 935 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.77.935

9. D. C. Johnston, Adv. Phys. 59, 803 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/00018732.2010.513480

10. G. R. Stewart, Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1589 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1589

11. M. K. Wu et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 908 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.908

12. T. H. Geballe et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 8, 313 (1962). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.8.313

13. J. E. Hirsch, M. B. Maple, F. Marsiglio, Physica C 514, 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physc.2015.03.002

14. X.-L. Qi, S.-C. Zhang, Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1057

15. A. H. Castro Neto et al., Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.81.109

16. Y. Saito, T. Nojima, Y. Iwasa, Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16094 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.94

17. L. P. Gor’kov, V. Z. Kresin, Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 011001 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.011001

18. M. G. Alford et al., Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1455 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1455

More about the authors

Art Hebard and Greg Stewart are professors of physics at the University of Florida in Gainesville.