Obliterating Myths About Minority Institutions

DOI: 10.1063/1.2117823

The shelves are full of public and private reports 1 – 3 that deal with the importance, in the US, of attracting more minorities to science and that propose a wide variety of solutions for achieving that goal. Countless conferences have been held and speeches made. But rhetoric and reality are vastly different, and despite substantial investments by a number of federal research agencies, shockingly little progress has been made. For example, an analysis conducted at our request by the American Institute of Physics showed that in the 31 academic years from 1973 to 2003, only 21 African Americans, 56 Hispanic Americans, and 11 Native Americans earned doctoral degrees in astronomy.

We believe the lack of significant progress to date arises at least in part from common myths that appear to underlie discussions about why certain racial and ethnic groups are underrepresented in the sciences. Although nobody likes to admit it, everyone has heard some of these myths: “They” are not interested, not qualified, not ready—perhaps even not capable of succeeding—in the sciences. Some people say that because federal agencies have spent many years (and a considerable amount of money) trying and failing to make any significant progress, nothing can be done. Others say that because they see a few minority faces here and there, the problem has already been solved. We say that all of these myths are wrong.

The evidence behind our position comes from nearly eight years of work that we led as officials at NASA headquarters under the auspices of the former NASA office of space science. We feel that the approach we took and the results we achieved are broadly applicable and should be more widely known and discussed.

Separate and unequal

As professional scientists and science managers, we believed that existing NASA programs aimed at bringing minority universities into NASA science were generally misguided. On the surface, the programs seemed to do the right things. They matched minority institution faculty members with scientific mentors, and they funded projects that seemed to fall within NASA’s scientific purview. However, on closer inspection, it became readily apparent there were many flaws. The mentors were often involved only superficially, and the projects frequently were set-aside projects managed by equal-opportunity personnel who were well meaning but essentially disconnected from the mainstream of the agency’s science programs and from the universities themselves. Research institutes were set up that had little connection to the host university’s academic program. Technology programs were established for NASA missions that had been canceled. And laboratories at minority institutions often did “piecework” for NASA centers.

We decided to do something fundamentally different. Working from inside the NASA office of space science, we made a commitment to devise a program that would break down barriers and bring minority institutions into the heart of the NASA space-science program. To develop our approach, we consulted extensively with administrators, faculty, and students at a wide variety of minority colleges and universities. The first thing we asked was whether they were even interested in having space-science programs at their institutions. Up to that point, we had been told another myth—that minority institutions were just not interested in something as esoteric as space science. Much to our surprise, the response to our question was a uniformly resounding and enthusiastic “yes.” When we then asked why such programs didn’t exist, the response was even more surprising. “No one,” they said, “has ever invited us.”

Invited? We usually do not think of space science as something into which one must be invited. But as in most sciences, entry into space science is controlled by what is essentially an apprenticeship system. Entry requires going to a “recognized” graduate school and having an adviser who is a “recognized” expert in the field. Minority universities are usually not “recognized” within this unofficial but highly influential “guild” system. As a result, their students have no obvious pathways into space science, and their administrators and faculty members have no obvious ways to develop such pathways.

We next asked, “What would it take to develop a successful space-science program at your institution?” The responses boiled down to three basic recommendations that went beyond just supplying money: Develop credibility with the institutions by issuing a serious invitation from NASA and the space-science community; establish the mechanisms for building real partnerships with major players in space-science research; and provide the flexibility to build programs that make sense for each individual institution.

The discussions that led to these recommendations were revealing. We learned that science faculty members and administrators at minority institutions were quietly aware of the failings of existing federal programs. A number of the individuals we consulted—many having doctoral degrees from “recognized” institutions—were, in fact, insulted by the treatment they had received. They were weary of being placed in nonproductive partnerships, of being steered into projects that did not lead to forefront science, and of dealing with programs that were prescriptive to the point of being stifling. Most significant, they were weary of being patronized and being regarded merely as sources of highly sought-after minority students while not being recognized as professional scientists in their own right. In short, they were tired of being placed in situations that made them both separate and unequal.

A new approach

We took the comments of faculty and administrators to heart. By combining their recommendations with the methods we normally used to solicit and fund NASA research programs, we developed a new approach to minority-institution involvement in space-science education and research, and launched the program that has subsequently come to be known as the NASA Minority University and College Education and Research Partnership Initiative (MUCERPI) in Space Science.

Establishing genuine partnerships was a critical element of our approach. At our request, the NASA associate administrator for space science sent a personal message to all NASA-funded space-science researchers asking them to actively participate as partners with minority institutions. It is a credit to the space-science community that investigators at major research institutions across the country responded to that request by serving as partners on proposed projects. In our opinion, they did so because the NASA office of space science was clearly serious about addressing the issue, and because the investigators sensed a genuine opportunity to do something new and meaningful.

From the minority institutions’ point of view, MUCERPI offered exactly what they had wanted. It came as a direct invitation from a science organization within NASA rather than from a niche organization that was not directly involved in the mainstream of NASA’s activities. It required genuine partnerships, and it provided pathways for securing them. It offered the flexibility to tailor projects according to individual institutional situations: Proposals could contain any combination of research capability development, academic program development, and public outreach program development. The only major restriction was that the proposals had to be clearly aligned with NASA’s space-science research objectives and with the proposing institution’s own long-term strategic plans. Faculty members we talked with were typically teaching physics or working in related disciplines, and they were anxious to engage in space science. Some had been trying for years to find ways to do so; others were anxious to jump at the new opportunity being offered.

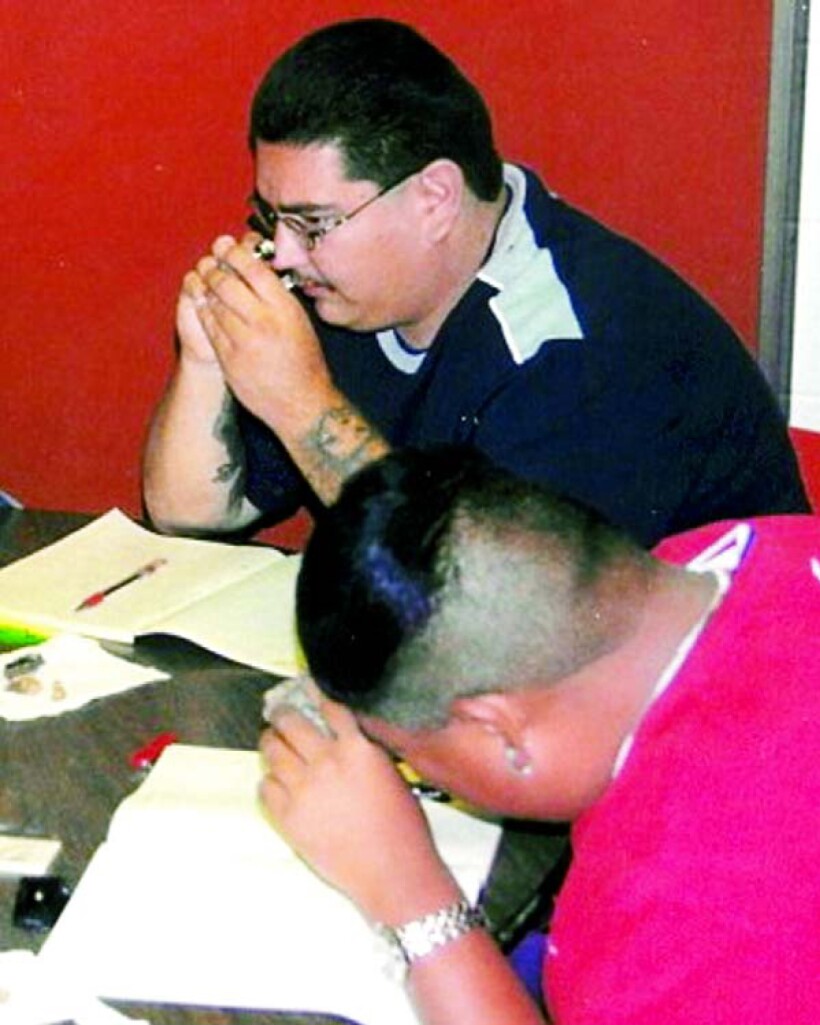

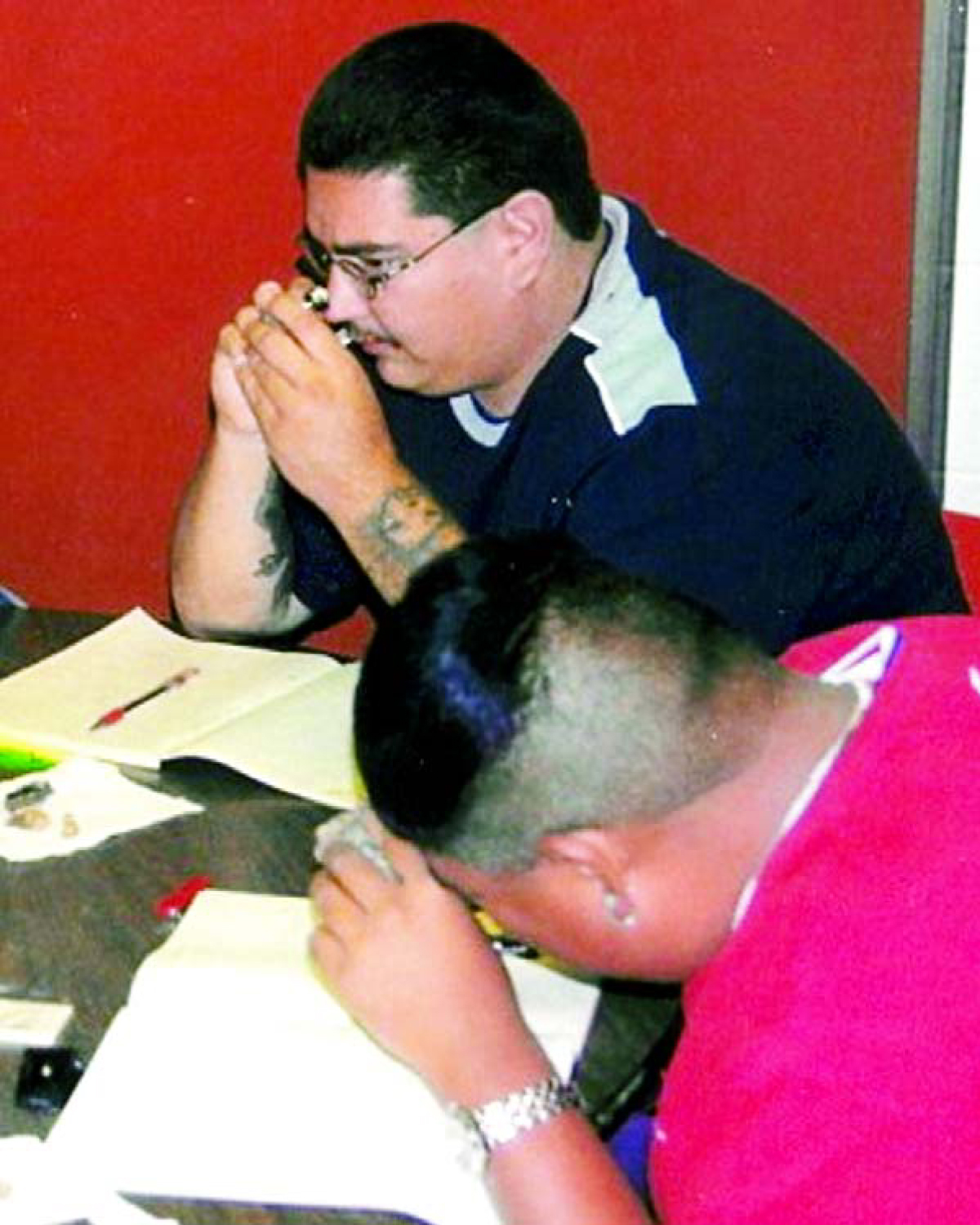

At Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute, a tribal college in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a new meteorite identification laboratory was established through a partnership with the University of New Mexico’s Institute of Meteoritics with support from NASA’s Minority University and College Education and Research Partnership Initiative. Students such as Robert Gakin (left) and Kevin Lewis (right) at first learned to identify the true meteorites among the many possible finds turned in to the laboratory for inspection. As the program progressed, the students became involved in planetary geology research with collaborators at UNM, the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, and the US Geological Survey.

JERRY SIMMONS

This first solicitation was vastly oversubscribed—which in itself was a significant measure of the interest generated. MUCERPI funded 15 projects with grants of up to $250 000 per year for three years (2001 through 2003). The program also provided the participants with ongoing post-selection support—regular conversations, meetings, and site visits—aimed at making the participants genuine members of the NASA space-science community. We kept them abreast of activities, programs, and plans emerging from the office of space science, and worked at identifying and immediately addressing issues that might be hindering any individual project.

As the program progressed, we were humbled by the achievements of the participants—achievements that obliterated any myths that underrepresented minorities and minority institutions were somehow not interested or not capable of succeeding in space science. After only three years, the 15 participating institutions had collectively created 68 new or revised space-science courses and 12 new or revised space-science degree programs. They had established 25 space-science faculty positions, the majority of which were tenure-track and were continued after the grant period was over. They participated in 50 collaborative space-science research projects with major research institutions and were involved in 10 NASA space-science flight missions or suborbital flight projects. They conducted a wide range of space-science teacher training and public outreach programs, and, in settings where space science had previously been essentially nonexistent, they brought students into the field (see, for instance, the

Space-science research at south carolina state university

Located in the small town of Orangeburg, South Carolina State University (SCSU) is a modestly sized historically black university of roughly 4000 students, most of them undergraduates. The vast majority of students, 95%, are African American, and 60% are women. SCSU offers bachelor’s degrees in basic science disciplines such as physics, chemistry, and biology, but until Don Walter joined the physical sciences faculty in 1994, SCSU had little to offer in the way of astronomy or space science.

Trained in observational astronomy at Rice University, Walter began introducing SCSU students to the world of astronomy. He engaged students in his research on gaseous nebulae and conducted astronomy education and outreach projects by piecing together resources from a continual stream of grants from NASA, NSF, and other funding agencies. Astronomy was alive at SCSU, but it depended heavily on the initiative of one faculty member.

NASA’s Minority University and College Education and Research Partnership Initiative offered Walter a chance to institutionalize astronomy. With MUCERPI as the incentive, the university made a long-term commitment to astronomy at SCSU, and it backed up that commitment by creating a new tenure-track faculty position in the discipline. By the second year of the MUCERPI award, Jennifer Cash had been hired to fill the new position, and several existing faculty positions had been redirected to focus on astronomy.

With that team in place, the program grew rapidly. A concentration in astrophysics was established for physics majors, and a minor in astronomy was offered for other majors. New courses in astrophysics and astrobiology were added to the curriculum, and existing courses for nonmajors were completely revised. A strong student response is clearly evident: Enrollments in space-science courses at SCSU now exceed 200 students per year.

Research collaborations grew as well. Walter began studying the infrared spectra of comets with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC). Cash began working on three-dimensional models of stars with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Another faculty member, James Payne, worked with LLNL scientists on the design of cryogenic photon-counting cameras. Students that Walter recruited, with MUCERPI support, from SCSU and other historically black colleges and universities were placed in internships at GSFC, LLNL, Kitt Peak National Observatory, and other research institutions around the country.

SCSU physics major Erica Lamar, shown here working on a new generation of astronomical CCD detectors at LLNL, was one of many students the SCSU MUCERPI program placed in research internships at major laboratories and observatories across the country. (Photo courtesy of the Advanced Detector Croup, LLNL.)

Having evolved from the initiative of one faculty member to a program that encompasses significant numbers of SCSU faculty, students, and external collaborators, space science at SCSU is now firmly woven into the fabric of the university.

Bolstered by these initial successes, we offered a second opportunity for new MUCERPI proposals. As was explicitly stated in the first program solicitation, MUCERPI was intended not to provide long-term institutional funding but to provide seed money for new activities whose support would then be picked up by each participating institution as part of its own mission. In accord with that philosophy, previously funded MUCERPI principal investigators (PIs) were eligible to reapply only if their new proposals represented major new directions or significant enhancements to their previous work.

The second solicitation was again heavily oversubscribed. The previous successes, coupled with the overall high quality of the new proposals, convinced NASA top management to increase program funding. The expanded MUCERPI included 16 projects, 6 of which were from new PIs, for the years 2004 through 2006. The projects’ annual budgets were increased to up to $275 000. In an interesting progression, many of the MUCERPI PIs who had concentrated on building academic capabilities during their first three years turned to developing research capabilities in their second three years. Boxes

Spreading the success

Are the successes reported here anomalies, or are they replicable? Certainly not every accepted project was successful, but the vast majority of projects managed to dazzle us with what they actually accomplished. Such successes can be replicated at other institutions and in other areas of science. To do so requires taking on the attitudes and levels of commitment displayed by those involved in successful MUCERPI projects. For scientists at major universities and research laboratories, it means believing that colleagues at minority institutions are exactly that: capable scientific colleagues. It means taking the initiative to meet minority-institution faculty members, to seek out those with related interests, and to invite them into genuine collaborations. It means asking—and listening to—potential partners at minority institutions about the situations on their own campuses, about what they would like to do as scientific partners, and about what they need to participate effectively. It means following up promises with continued support, shared resources, and inclusion in meetings, seminars, and conferences. While these may seem like challenging tasks, they are not that different from what one normally does with colleagues at “recognized” institutions.

The New York City space science research alliance

With a doctoral degree in relativistic astrophysics and a dedication to serving the Harlem community in which he grew up, Leon Johnson dreamed of bringing the world of space science to his students at Brooklyn’s multiethnic Medgar Evers College. The Minority University and College Education and Research Partnership Initiative offered him the opportunity to do so.

Johnson gathered colleagues from colleges throughout the City University of New York (CUNY), added collaborators from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), and created the New York City Space Science Research Alliance. In its first three years under MUCERPI, the alliance emphasized the development of academic programs. Eighteen new or upgraded space-science courses enrolled 262 students from throughout the CUNY system, and an innovative system-wide space-science degree program was established. Students at any CUNY campus could major or minor in space science by taking cross-listed courses at colleges throughout the system.

In the second round of MUCERPI, Johnson launched a campaign to get the CUNY colleges more seriously involved in NASA space-science research. Twelve CUNY faculty members participated in Chicago 2004, a workshop sponsored by the NASA office of space science to seed new scientific partnerships between space scientists at major research institutions and minority or minority-university faculty members. A special program to assist junior CUNY faculty members in initiating space-science research projects was established, and more than 50 undergraduate students participated in research experiences. Research mentors from CUNY, GISS, AMNH, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory oversaw projects in astrophysics, atmospheric sciences, magnelospheric physics, and planetary studies. In a first step toward developing their own flight-project capabilities, Medgar Evers College faculty and students have begun to build and fly small experimental payloads on high-altitude balloons.

Thanks to MUCERPI and Johnson’s efforts, space science has blossomed throughout the CUNY system. But what is perhaps even more important, space science has also penetrated the streets of New York. Writing in the Village Voice newspaper, Eric Baard captured the essence of Johnson’s work:

In places like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Harlem, and the South Bronx, under a light-polluted sky cut to ribbons by grids of looming buildings, the stars till tug at young minds. “I am the ghetto child, / I am the dark baby. … And yet / I am my one sol self, / America seeking the stars,” wrote the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. Now the National Aeronautics and Space Administration wants a new generation of this city’s African American students not only to feel the cosmos through metaphor, but to know it in physics.

5

In places like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Harlem, and the South Bronx, under a light-polluted sky cut to ribbons by grids of looming buildings, the stars till tug at young minds. “I am the ghetto child, / I am the dark baby. … And yet / I am my one sol self, / America seeking the stars,” wrote the Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes. Now the National Aeronautics and Space Administration wants a new generation of this city’s African American students not only to feel the cosmos through metaphor, but to know it in physics. 5

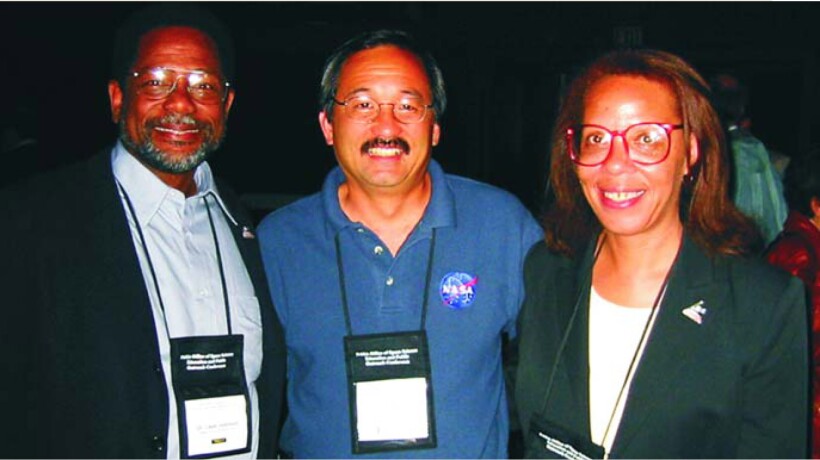

The photo shows Johnson, one of us (Sakimoto), and Medgar Evers computer scientist Shermane Austin at Chicago 2004.

For funding agencies, it means making the involvement of minority institutions part of an agency’s main line of business rather than dealing with them through a specialized organization detached from the real action. Minority-institution programs should be managed by the science organizations in an agency. Minority-institution program administrators should have the authority necessary to set policies and direct activities within the organization, to influence activities of scientists outside the organization, and to see that the outcomes of minority-institution programs directly contribute to the agency’s scientific objectives.

Solicitations should be open to meeting the broad needs of all types of minority institutions while ensuring that those institutions can become genuinely involved in the work of the agency. Just sending money doesn’t do the job. The agencies also must actively work with the institutions following selection. The communities of scientists regularly funded by the agencies must be motivated and mobilized to serve as mentors and colleagues to newcomers from minority institutions, and they must be willing to become substantially involved. Carrying out these mandates may entail significant changes in the agencies’ ways of doing business, but standard procedures have not been very successful to date. The myths are wrong. Actions can replace rhetoric. Positive results speak for themselves. Something different is possible. We hope that our experience will make the road a little easier for those who follow.

Salish Kootenai College

On the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, nestled at the foot of Glacier National Park, lies Salish Kootenai College, a tribal college established to serve members of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. As is typical at many tribal colleges, SKC science programs emphasize practical life areas such as environmental science, information technology, and nursing.

Under previous grants from NASA and other sources, SKC developed a variety of precollege outreach programs and, under NSF’s Alliance for Minority Participation Program, led a consortium of tribal colleges in improving undergraduate enrollment and performance in the sciences. They worked hard and successfully at filling the science pipeline with Native American students.

With support from NASA’s Minority University and College Education and Research Partnership Initiative, physics instructor Timothy Olson brought SKC into the world of space science. His initial MUCERPI project was a very modest experiment in sampling student interests. He developed four basic courses in astronomy, and through them he found strong student interest in space science. By the end of the three-year award period, 26 students had enrolled and many of them had conducted student research projects as part of their class work.

In the second round of MUCERPI awards, Olson took a bold step. He forged an alliance with the Montana Stale University (MSU) space science and engineering laboratory, and SKC faculty and students became collaborators in several solar-physics research projects. They set to work on such tasks as devising procedures for unpacking the overlapping solar spectral images obtained by MSU’s multi-order solar EUV [extreme ultraviolet] spectrograph (MOSES) sounding rocket project.

Then serendipity struck. Kenneth Edgett of Malin Space Science Systems was preparing to compete for an instrument slot on NASA’s 2009 Mars Science Laboratory (MSL). Looking for partners to fill out his proposal team, he learned about the work that Olson and his students had been doing. After a series of discussions, he invited Olson to be a co-investigator on his Mars hand lens imager (MAHLI) proposal. Late last year, NASA selected MAHLI to fly onboard MSL. The small color camera will provide high-resolution, close-up images of Martian rocks and fines. Olson and SKC students will contribute to developing, testing, and performing data-analysis procedures for MAHLI, such as compressing vertically stacked series of images before transmission to Earth.

In 2009, a tribal college is going to Mars.

Carrying 11 scientific instruments, including the Mars hand lens imager on which Salish Kootenai College is a collaborator, the Mars Science Laboratory, shown here in an artist’s rendering, will collect Martian soil samples and rock cores and analyze them for organic compounds and environmental conditions that could have supported microbial life now or in the past.

NASA/JPL

We are deeply indebted to Edward J. Weiler, NASA associate administrator for space science during most of the period that MUCERPI was being planned and implemented, for his whole-hearted and unwavering support of our efforts.

References

1. Interagency Working Group on the US Scientific, Technical, and Engineering Workforce of the Future, Ensuring a Strong U.S. Scientific, Technical, and Engineering Workforce in the 21st Century, National Science and Technology Council, Washington, DC (April 2000).

2. The US Commission on National Security/21st Century, Road Map for National Security: Imperative for Change; The Phase III Report of the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, Washington, DC (February 2001).

3. Building Engineering and Science Talent (BEST), A Bridge for All: Higher Education Design Principles to Broaden Participation in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics, BEST, San Diego, CA (February 2004).

4. P. Sakimoto, ed., National Aeronautics and Space Administration Space Science Education and Public Outreach Annual Report, fiscal year 2003, NASA Office of Space Science, Washington, DC (June 2004).

5. E. Baard,Village Voice, 23 April 2002, p. 37.

More about the authors

Philip Sakimoto, now on the physics faculty at the University of Notre Dame, was previously at NASA headquarters as program manager for NASA space science education, public outreach, and diversity initiatives.

Philip J. Sakimoto, 1 University of Notre Dame, US .

Jeffrey D. Rosendhal, 2 NASA, US .