From the archives: SCIENCE and the War on...

DOI: 10.1063/1.2761802

Editor’s note: Fifty years ago, with the first International Geophysical Year (see the article by Fae Korsmo on

IN THE LAST FEW YEARS I have had more than usual opportunity to reflect on the aims, ambitions and purposes of science. Lack of real opportunity to engage in active scientific research and forced concentration on science administration has meant that I have been more concerned with policy decisions than the details of any particular project. This has been a valuable interlude because the horizons of science are necessarily broader than any single project could ever be.

Out of sheer necessity it has become important to compare the value of one activity with another, to decide which of two alternatives is more important. This is a very different kind of decision than one customarily must make in personal research programs.

It is a very curious fact that there is no such thing as a “philosophy of science” or a “scientific culture.” If such things existed they would provide a standard of values against which we could weigh our actions. Instead we have a kind of anarchy where every individual proclaims his importance at others’ expense.

In our own research projects we make our own decisions, set our own goals and choose our own standards. But concentration on a particular direction in a particular aspect of science can rapidly generate the feeling and belief that science is what I do, and this attitude in turn can lead to the belief that anything in which I become interested should be supported by the rest of society as a true scientific endeavor. It is a philosophy that is at the same time a comfort and a justification. It is, however, far from being the whole story.

Science is important to society principally because it is relevant. That which we call “modern science” is just about as old as the industrial revolution and in fact is contemporary with it. Scientific development and industrial development have progressed side by side for the last 200 years. As scientists we can easily delude ourselves into believing that we occupy the role of leaders in this progression. But history shows that this is not always so; for sometimes we are followers of the industrial progress.

Does science follow need?

19th century science was at the same time important and basic to scientific developments that followed, but it was also relevant to the industrial revolution that was occurring at the same time. Mostly, however, it was industry that was leading and science that was following. This sequence was true for most of the chemical industry, communications technology and thermodynamics. After all, steam engines were in use before the second law of thermodynamics was enunciated, and water was boiled long before the equation of state was ever written down. Of course there were many contrary examples in which science was leading and industry followed. This order was true of some chemical industries, and it has been particularly true in the last few decades of the electronics industry, semiconductors and, most important of all, nuclear energy. In this respect, science is just beginning to be ahead of the game: the scientist is leading and industry is following. Looking at the past 200 years, we might surmise that the two roles are about 50-50; that is, science can and does follow the needs of society as much as it leads those needs and causes the establishment of new industries.

This is very healthy owing to the great danger in being the perpetual leader. Under those circumstances, there is always a tendency not to look back. There always was and presumably always will be a need for the kind of scientific activity that is so far ahead of the field that it has no need to look back and nothing to gain in doing so. Unfortunately we have a tendency to glorify such activities and give them a special place in our scientific society. If we were to concentrate exclusively on such activities, we would probably endanger our own society. Such forms of extremism can easily become obsessions and lead to self-destruction. The prime example of this was the Mayan civilization whose intellectuals were also the leaders of society. They concentrated on astronomy to such an extent that they established the length of the year to incredible precision but failed to consider the needs of their own society even to the extent of not inventing the wheel. As a result, the society that supported them failed to maintain the pace and the total civilization disappeared.

Of course we are not in danger of destroying ourselves. But this possibility is the essential content of all the debates on the balance between basic and applied research. There is a great deal that the scientific community can do to accept the problems that face our own society and apply to them the same kind of scientific reasoning that we apply to problems which we choose ourselves. After all, the man in the street is more likely to accept our claims for supporting the luxury of basic science if we can also demonstrate that science is eminently practical and essentially relevant.

Nowadays the problems of society seem to occur as wars. This interpretation is perhaps only a recent popularization but it is revealing because a war implies a struggle. It also implies that someone will win. In recent years we have heard of the war on poverty, the war on slums, the war on pollution and the war on crime, the war on ignorance, on the population explosion and hunger. There is little doubt that all these problems are very significant—some in this country and some abroad. I would like to urge that we in the scientific community should investigate all these problems and recommend ways in which scientific knowledge, training and techniques could be of value in winning the wars. Perhaps it should be emphasized at the outset that this is not easy and that there are no existing channels of communication between scientists and those engaged in wars either as soldiers or as victims. In spite of the well established value of science to society, we have not succeeded in developing managerial techniques that seek the advice of the scientific community in such matters.

It is, of course, impossible to write about the scientific content of these various battles in any one discussion. Rather than go briefly and with great shallowness through all of them, I have chosen to discuss just two: the wars on pollution and on crime.

Air pollution

Like the weather, we all talk about pollution but do nothing about it. Air and water pollution are only two of the facets, but they are particularly serious and immediate problems in our large cities.

Cats and foxes bury their feces. Dogs do not, but keep their lairs clean. Man is among the very few who befouls his own habitat to the point of suicide.

Until recently pollution was a problem for the next generation. Because we are selfish animals and prone to procrastination, pollution could, therefore, be ignored. Indeed pollution was often a matter of pride. Those “dark Satanic mills” were a symbol of prosperity, not decay, and in my own home town of Bradford in the heart of industrial England the guiding phrase was, “Where there’s muck there’s money.”

Now, however, pollution has reached the point at which one man’s pollution is his own poison. My own automobile poisons me; my own sewage fouls my water supply, not my children’s. We therefore protest.

Almost daily one reads and hears of complaints and demands. Naturally the loudest noises occur on such occasions as the recent outbreak of smog in New York, and tend to disappear when the weather improves. Such public outcries serve to dramatize the situation, but we should respond calmly and rationally. A quick response to the fire alarm could produce a temporary improvement but it may also delay the ultimate solution. Outcries usually hinge on the legal component—“Why can’t they pass a law to stop… etc.” There is often a simple answer to such a question. If one passed a law preventing utilities from polluting the atmosphere, we would have little or no electrical power with which to conduct our daily lives. Nuclear power will help but we cannot wait. If one passed a law preventing our steel mills from polluting the air, they would either close down or move to a community that did not have such laws. The impact would be very serious—loss of employment and loss of taxes. Responsible communities carefully avoid such situations.

It is this kind of situation that indicates that pollution must be tackled on a national rather than a local basis. Industries will be more likely to respond if there are no local advantages and no special favors.

Air pollution is as much a scientific problem as it is a legal one. Pollution must be reduced. We cannot continue to use our atmosphere as a sewer; for we will commit suicide by drowning in the feces of our own industrial prosperity. But how far must we reduce the level of pollution? To set limits too low would penalize industry and raise the cost of production. To set limits too high may endanger the health or life of the people who breathe the air. Limits can only be established by understanding the total effects of the pollutant on the environment and on the affected organisms. We scientists can help by studying these problems carefully and searching for appropriate and economic solutions.

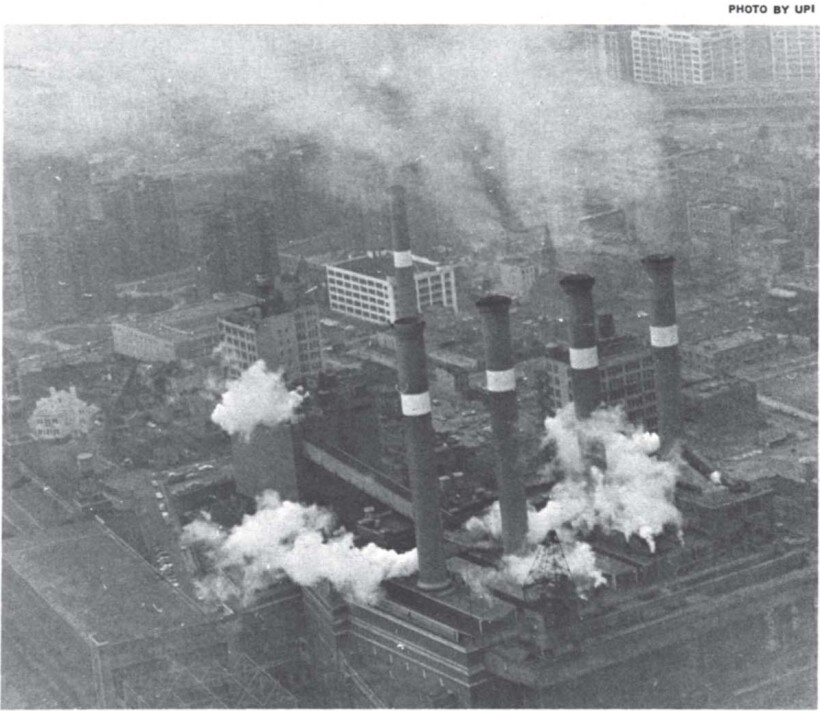

NEW YORK SMOG: “We cannot continue to use our atmosphere as a sewer; for we will [drown] in the feces of our own industrial prosperity.”

PHOTO BY UPI

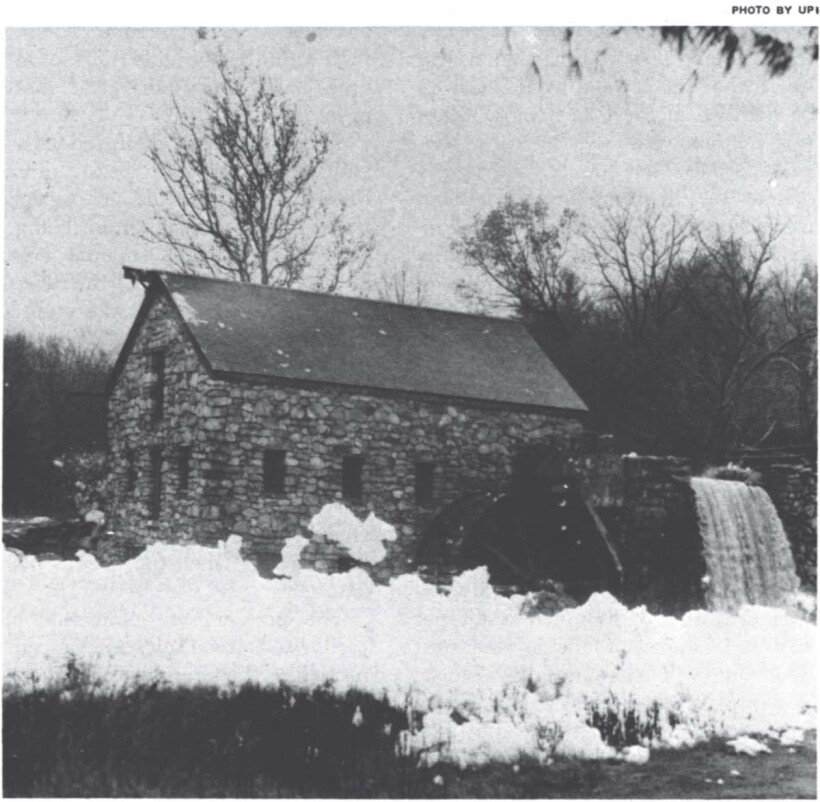

THAT’s NOT SNOW BUT SOAPSUDS burying the old grist mill as the sewerage overflow from the town of Marlboro, Mass. runs into Ford’s pond and then down the stream to the mill.

PHOTO BY UPI

The detection problem

This problem is, in many ways, analogous to the problem of radioactive fallout. From the earliest days of the use of radioactive materials we were aware of the dangers. Thousands of mice and guinea pigs have been used to study the effect of small amounts of radioactivity on living systems. Networks of information and decisionmaking bodies now exist on a national and international scale to set standards. Similar things could be done in the area of pollution.

Very sophisticated and extremely sensitive measuring devices can measure extremely small amounts of radioactivity. We have few if any instruments that can measure pollution. The definition of a noxious odor is still a subjective one that must be established in a court of law. Of course, for every witness who claims a noxious odor existed, one can find another who says he could smell nothing. If we cannot measure pollution we have no means of control because we can not tell when the situation improves.

Only on a gross level can we be sure of some facts. We put ten million tons of sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere every year! All the tetraethyl lead that is manufactured in this country is exhaled by our autos and is available for breathing! How do we make it economical and practical not to do those things? In many cases, the solution will not be the obvious one of designing or devising a machine for taking smoke out of flue gases. It may be the less obvious one of changing the basis of the chemical or physical system involved in the process. In any case, it is a systems problem. One should not clean up the air by dirtying the water or vice versa.

We have a supreme example of just such a bad situation in Chicago. The sanitary district treats sewage from the city but is left with a large amount of sludge on its hands. Apparently the only way they have devised to dispose of this sludge is to dry it in ovens. If anyone wants, literally, to have a taste of our air pollution problem in Chicago, I invite him to take a drive along the Stevenson Expressway towards Argonne when there is a north wind blowing. The stench is unbelievable and almost unbearable.

I have used Chicago here as an example only because I am familiar with this particular problem. However, every large city has similar difficulties; and if their plants are less modern than Chicago’s, it is quite conceivable that the situation would be even worse.

Of course, a principal contribution to air pollution is the automobile. It dumps a large number of contaminants into the atmosphere, but we do not know how much, and we do not know how harmful these pollutants are.

“WE ARE … not in the position of the ostrich and cannot bury our heads until [beer cans] disappear.”

Each one of us is suffering from lead poisoning from inhalation of gasoline fumes. It is nonsense to protest that it is harmless; we just don’t know and it is a difficult scientific problem to find out. In only a few years no human being will be free from lead poisoning; that is, we will no longer have a standard of reference. In addition oil companies are now experimenting with nickel and other additives. What damage, if any, these new additives will do no one knows. We can be sure, however, that the Food and Drug Administration would not allow such additives in food without some evidence as to their effect on life.

The automobile is also responsible for another surprising air pollutant-asbestos fibers. Again each of us has a considerable amount of asbestos in our systems, and we have no idea as to its effect. Two scientific problems exist here: the effect of asbestos poisoning and the search for a reasonable alternative.

Of course, one of the main methods of reducing air pollution would be to develop a more efficient electrical storage battery so that we can have electric automobiles. This is a difficult scientific problem whose solution will not be appreciated by the oil companies and which may not even be possible.

If it is ever going to happen, we will need more radical new ideas on energy-conversion techniques to reduce the mass of the total system.

Water pollution

Water pollution is an almost universal phenomenon. Industrial pollution may be a necessary consequence of an industrial economy and sewage is certainly a natural consequence of civilization, but there is no reason why we should be content with the amount of contamination. To take the example of sewage, we are using a system of treatment that is centuries old and consists, basically, of doing nothing at all.

Our own system here in Chicago is an interesting example. It is a very large plant, reputedly the largest in the world, and it requires huge amounts of water to operate; for the effluent must be diluted to an acceptable level. The reader may be aware of the legal difficulties involved in drawing water from Lake Michigan. In fact only a short time ago it was stated that the sewage would have to be dumped in the lake if more water was not allowed.

Apparently no one has devised a system for treating sewage without using huge amounts of water. Processes undoubtedly exist that could be applied: fluidized bed techniques, for example, or even direct distillation using nuclear heat. Plant size is about the same as that being discussed for applications in nuclear desalination. Various groups in the country are considering an enormous nuclear desalination plant to take the salt out of a billion gallons of sea water per day and provide electric power as a sideline. At these sizes, the plant may be economical. In Chicago, the sanitary district uses about this much water per day and happens to be located next door to a Commonwealth Edison power plant along the canal. Therefore collaboration may be possible. After all, the problem of taking sewage out of water is not more difficult, and may be much easier, than that of taking salt out of sea water.

A scientific systems approach to the problem of water pollution could have very significant economic effects. For example, those communities along the coast could consider using sea water for the treatment of sewage—particularly states like California where fresh water is expensive. Such a system is under test in England and has obvious advantages. In situations like this where drinking water is expensive, it seems ridiculous to use it to dilute sewage effluent. The cost of developing a sea water plant may be less than the cost of providing new pipelines for fresh water.

Need for standards

We need ways to measure industrial water pollution. We need information on which to base standards, and we need ways to reduce it even if reducing it means changing the chemical or physical basis of operation for the whole process.

As with air pollution, the difficulties of setting acceptable standards of water cleanliness are formidable and should not be treated in an arbitrary way. It is attractive to think that all our streams and rivers may be once again filled with potable water and such a thing may be feasible. On the other hand, society may find the cost prohibitive.

So far we have discussed only air and water pollution, and although these are the most obvious aspects of pollution, they are far from being the total problem. For example, most of us are painfully aware of the difficulty with beer cans. The old steel beer cans were bad enough. But even they are not as bad as the aluminum ones because the aluminum ones do not rust and have a lifetime that is virtually infinite. We are, therefore, not in the position of the ostrich and cannot bury our heads until they disappear. One obviously needs a beer can that disintegrates when the beer is poured out.

The problem of automobile junkyards needs to be solved. A recent report from the President’s Science Advisory Committee panel on environmental pollution has noted, “Scrap iron and steel are generated at a rate of 12 to 15 million tons a year, of which about a third consists of derelict automobiles. The fraction recovered for use has declined substantially.”

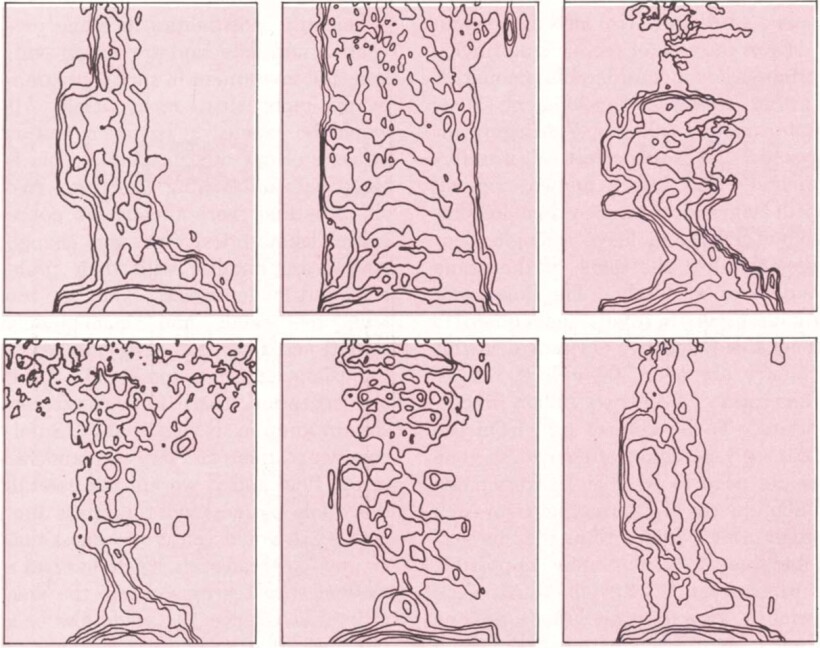

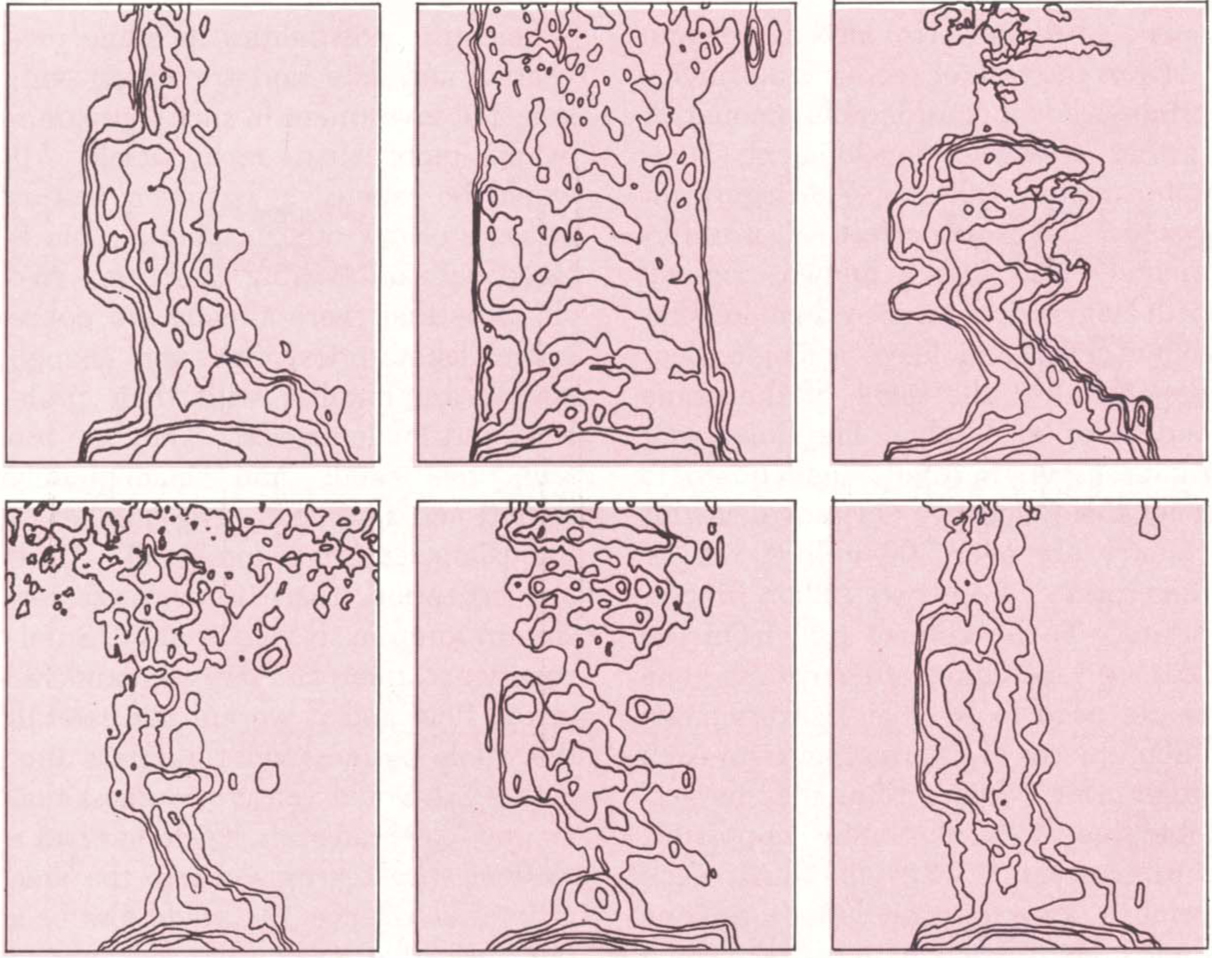

VOICEPRINTS of speakers saying “you.” Time dimension is along horizontal axis, frequency along vertical and loudness levels in contours. Upper left and lower right prints are of same person.

The problem is partially an administrative one in making it economical to retrieve the materials from these scrap heaps, and it is partially a scientific problem to produce an economical method for separating the many different kinds of materials. The whole process is analogous to the second law of thermodynamics; for the steel in automobiles is taken out of the ground in a convenient form, iron ore. It is used for a while and then dumped back into the ground in a much more inconvenient form. Even when allowed to rust, the final product is much more difficult to use than was the initial material.

The scientific and technological content of the pollution problem is very high indeed, and one should not begin the war on pollution without involving modern science. Indeed this problem could be one of the biggest that science and technology ever attempted to solve because in searching for a solution one must study the population of the world as users. We must look at each individual as an organism that accepts materials in one form and passes them on in another. We should do this with food and drink, automobiles, clothes, appliances and so on. Everything that we use in everyday life merely comes to us in one form and leaves us in another. When it leaves, it becomes pollution. We must devise ways of recycling the raw materials and making it economical to do so. This system analysis will obviously become an infinite process.

Even if we ever catch up with today’s problems there is always tomorrow. Products change all the time and need to be integrated into the system. As an example, I once received in the mail a sample of a paper substitute that was supposed to be virtually indestructible. It is difficult to imagine a more frightening prospect than that.

Crime problem

Another problem that has attracted much attention is crime, and once again there is much that science can do to help. The growth of criminal activity is too well known to need explanation.

Perhaps, however, some statements that appear in a recent report by the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice would help to dramatize the situation.

There are about 10 000 homicides per year in the US but less than 100 convictions; over two million burglaries and 500 000 automobile thefts. There are about 5 000 000 arrests for index crimes every year, and so the average probability of any person being arrested is around 2.5% per year.

It is almost impossible to calculate the cost of crime to society, but a figure of $20 billion per year would be reasonable.

This is only part of the story, however, for the truly alarming aspect is the extremely rapid growth rate. As the size of the cities increases, we can expect the crime rate to rise as a high power of the population density. In the first place, there are a greater number of people with criminal instincts within the city, and there are a greater number of opportunities for crime. As a minimal figure, I would tend to take as a guide the number of people multiplied by the interaction rate, that is, the number of people that any one individual can interact with in the course of the day. Minimally, then, the crime rate would be expected to rise as the square of the population.

Perhaps, too, frustration plays a part by increasing the amount of criminal instincts per person with an increase of population density. I must say I am not convinced that increasing crime is entirely a matter of frustration. I prefer to look at the matter as a statistical one.

As with pollution, the crime rate is now so high that it has a direct impact on every one of us. We take precautions like locking our car doors and discouraging our wives and children from walking at night.

Again, as with pollution, the usual reaction is “Why don’t they pass a law…?” or “Why don’t they enforce the law…?” These are reasonable questions, but a world where the number of new laws is rising rapidly is just as uncomfortable as one in which lawbreaking is rising—and perhaps these facts go together in any case. On the other hand, if all existing laws were strictly enforced, civilized life would cease.

Science could help in the war on crime. There are many modern techniques and methods that could be developed as crime detectors and deterrents.

Every reader of Physics Today can think of devices and systems that could be applied to police work. We all deal with sophisticated measuring, analysis and mathematical techniques that are sorely needed by the law enforcement agencies. These techniques would span the range from neutron activation to gas chromatography and from information retrieval to system analysis.

We know that these things would be of value in the war on crime, but we also know that no local police department can afford to pay this price. Nuclear reactors and large computers are too expensive for the local tax burden.

In addition these techniques would need to be adapted to their new purpose, and new research and development programs would have to be undertaken. Who is going to do this important work?

Methods against crime

The identification of samples of hair by neutron activation is a particular case in point. Work is going on already in this country on that problem, but it is not an easy one and even when solved will not be easily applied in all parts of the country. Other measuring equipment can also be very expensive and may require considerable development and adaptation to police purposes.

Many physicists are working in some aspect of pattern recognition. The high-energy physicist must recognize the characteristics of his bubble chamber pictures. The biophysicist must be able to recognize objects under his microscope. The electron microscopist must be able to understand the pictures that he takes. In very many areas of science a picture is the final product of the available equipment, and the picture must then be interpreted. Several groups of people are working to build machines that can recognize these pictures and patterns and convert them into numbers for computer processing. It would be quite conceivable to develop pattern-recognition devices for police purposes. They could, for example, be taught to discriminate among photographs of faces. If we could store millions of photographs of faces in a computer and select the right one from this store, we would give our police a very powerful kind of weapon.

Even the task of recognizing fingerprints needs a considerable amount of further scientific development. It is unfortunately true that the fingerprint system is far from perfect. It is unfortunately true that a known criminal with fingerprints on record could commit a crime and leave a single clear fingerprint at the scene of the crime and never be caught. The fingerprint filing system is totally inadequate to meet this demand. On record in this country are over 200 million sets of fingerprints, over two billion fingerprints. To be able to pull from the files a matching fingerprint, one would need to be able to extract two billion pieces of information from each fingerprint. Such a thing may be possible but it is absolutely impossible with current systems in which each print is assigned one letter and one digit. Here again pattern-recognition devices and computer memories could be a great help and are probably the only hope.

Other devices could be developed or are being developed. Voiceprints, for example, have shown some successes and could be developed further. It appears from preliminary studies that a voiceprint may be as personal as a fingerprint.

In crime prevention there is again much that science could conceivably do. New communications systems for the police that would provide additional strength to the individual policeman would help. Improved communications systems from the pedestrian in the street to the police could help to reduce crime on the streets. Science and technology could be used to perform system analysis studies of many facets of our everyday life to determine whether the total system could be changed to reduce the crime rate. Our particular way of using money is a good example. Combining the telephone and police call system is another. Perhaps a better example is the vicious circle we are in on the matter of petty gambling. For the law which was originally designed to protect the poor has now become a law which persecutes them. It is at least conceivable that rewriting the law could in itself eliminate much of the difficulty and associated crimes of the numbers racket.

Scientific possibilities in crime prevention and detection are almost end-less, and investment in such a program would more than repay itself. It would be expensive, however, and as in some of our other examples, one is faced with an existing structure. We all know that there already are police crime laboratories, but not enough people are familiar with their problems and inadequacies. They are too few, too small and inadequately staffed and supplied. The number of forensic scientists is too small. With one exception, there is no professor-ship in forensic science at any US university and there are very few students in the field and if we are not careful, the whole business will disappear altogether. I would venture to guess that no one who reads this article has had a student who has moved into the area of forensic science. It would also be a fair guess that no one has encouraged any student to consider the study of forensic science.

Responsibility of science

In concluding I would like to note once more that society is faced with a large number of problems of varying degrees of importance and urgency. Each of these problems has some technological or scientific content if we are willing to look for it. The new science and the new technology that are involved can be as exciting and interesting as many of the projects in which we are now employed. It certainly could be a more rewarding form of endeavor.

It is up to the scientific community to point out where they can help. Our existing governmental structure cannot be expected to seek our advice and help because they are much more accustomed to solving problems by new legislation or new appropriations. Until we have a more perfect arrangement (from our point of view), we will simply have to employ our own initiative.

Perhaps we will eventually have a system of National Crime Laboratories or National Pollution Laboratories just as we now have Argonne and Brook-haven. Perhaps better solutions exist, but until we can make ourselves heard, the scientific content of these problems is in danger of being grossly underestimated.▪

More about the authors

The author, born in England and educated at the University of Liverpool, has headed Argonne National Laboratory since 1961. This article is based on a speech delivered at the APS 1967 meeting in Chicago.