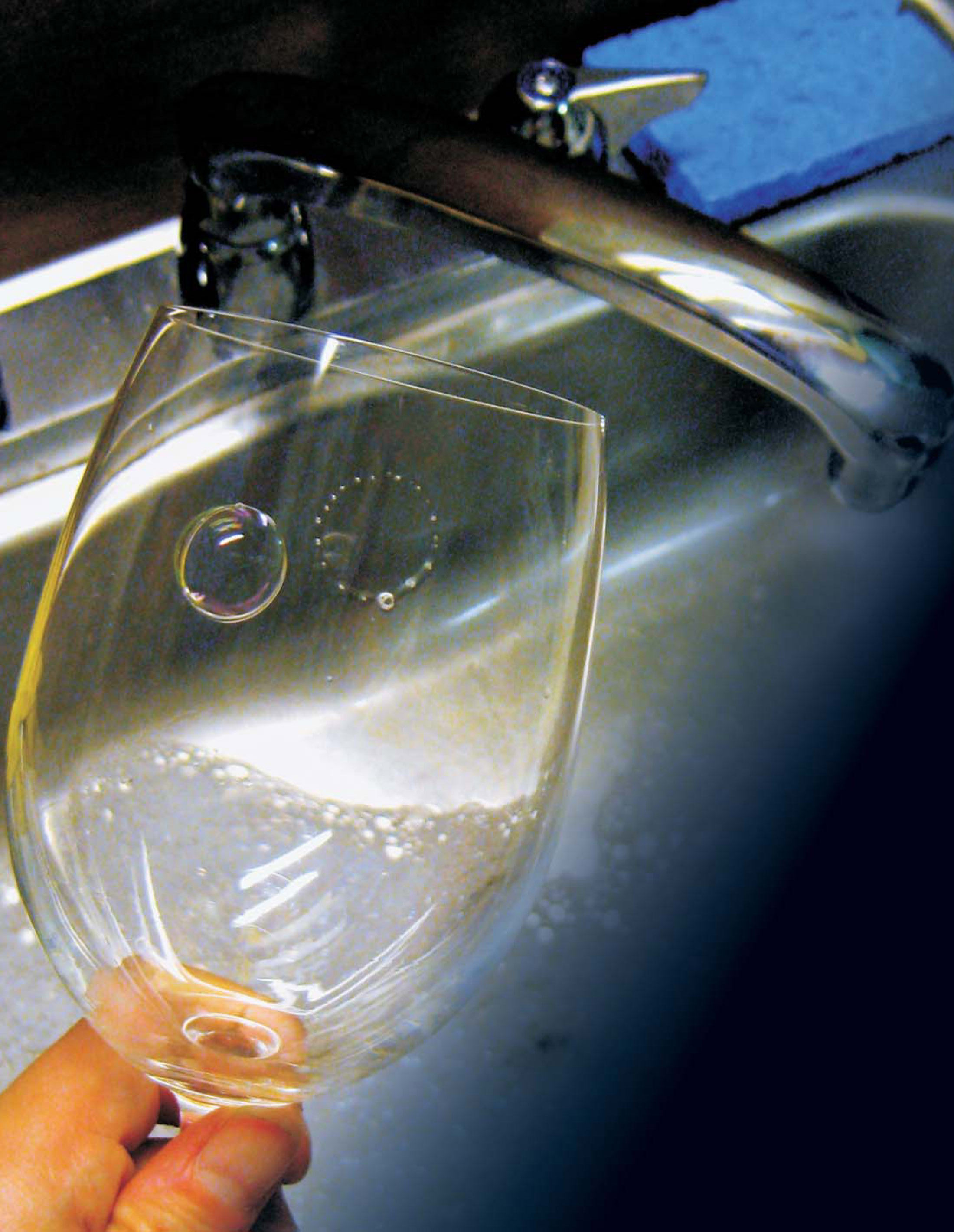

Bursting bubbles

DOI: 10.1063/1.3463637

When a bubble on a liquid or solid surface ruptures, it doesn’t always vanish as one might expect. It can sometimes form a ring of smaller bubbles. Those daughter bubbles can likewise decay in a bubble-bursting cascade. Such behavior can be seen in a broad range of everyday settings, from ocean froth to Jacuzzis. Here, two comparable bubbles of ordinary sudsy dishwater were blown on a wine glass with a straw; when the right bubble popped, it left a ring of smaller bubbles around its perimeter.

Through experiments, simulations, and theoretical analysis, James Bird (Harvard University), Laurent Courbin (University of Rennes), and colleagues have uncovered the origin of the cascading behavior. When a bubble’s curved top film ruptures, capillary and inertial forces cause the film to fold onto itself, trapping air in one and sometimes two toroidal pockets. Then, as with a dripping faucet, surface tension breaks up the air pockets into rings of smaller bubbles. The team found that the details of the rupture—and whether daughter bubbles are produced—depend quantitatively on the ratios of inertial to viscous effects (the Reynolds number) and of viscous to capillary effects (the capillary number). Bubble cascades are of much more than academic interest. Bursting bubbles send up aerosols, such as the fizz at the surface of carbonated beverages. In pools and hot tubs, such aerosols have been implicated in the spread of diseases. Worldwide, the 1018−1020 ocean bubbles that rupture each second transport dissolved gases, biological materials, and energy to the atmosphere. Moreover, bubbles can have detrimental effects on glassmaking and other industrial processes. (J. C. Bird et al., Nature 465 , 759, 2010 http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09069

To submit candidate images for Back Scatter, visit http://www.physicstoday.org/backscatter.html

Photo by J. C. Bird.