A stormy life in atmospheric science

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5159

When Joanne Simpson (1923–2010) was awarded the Carl-Gustaf Rossby Research Medal in 1983, she was the first woman to win the award. The American Meteorological Society praised her outstanding studies of tropical convective clouds and her decades-long research on hot towers and hurricanes, which had transformed scientists’ understanding of the global circulation of heat. But her mother was unimpressed. “Everyone wonders why, if you are so good,” she sniped, “that you have not yet been elected to the National Academy.” That tension animates James Rodger Fleming’s gripping biography, First Woman: Joanne Simpson and the Tropical Atmosphere. Simpson’s research took her to the top of meteorology, but it couldn’t make her mother love her.

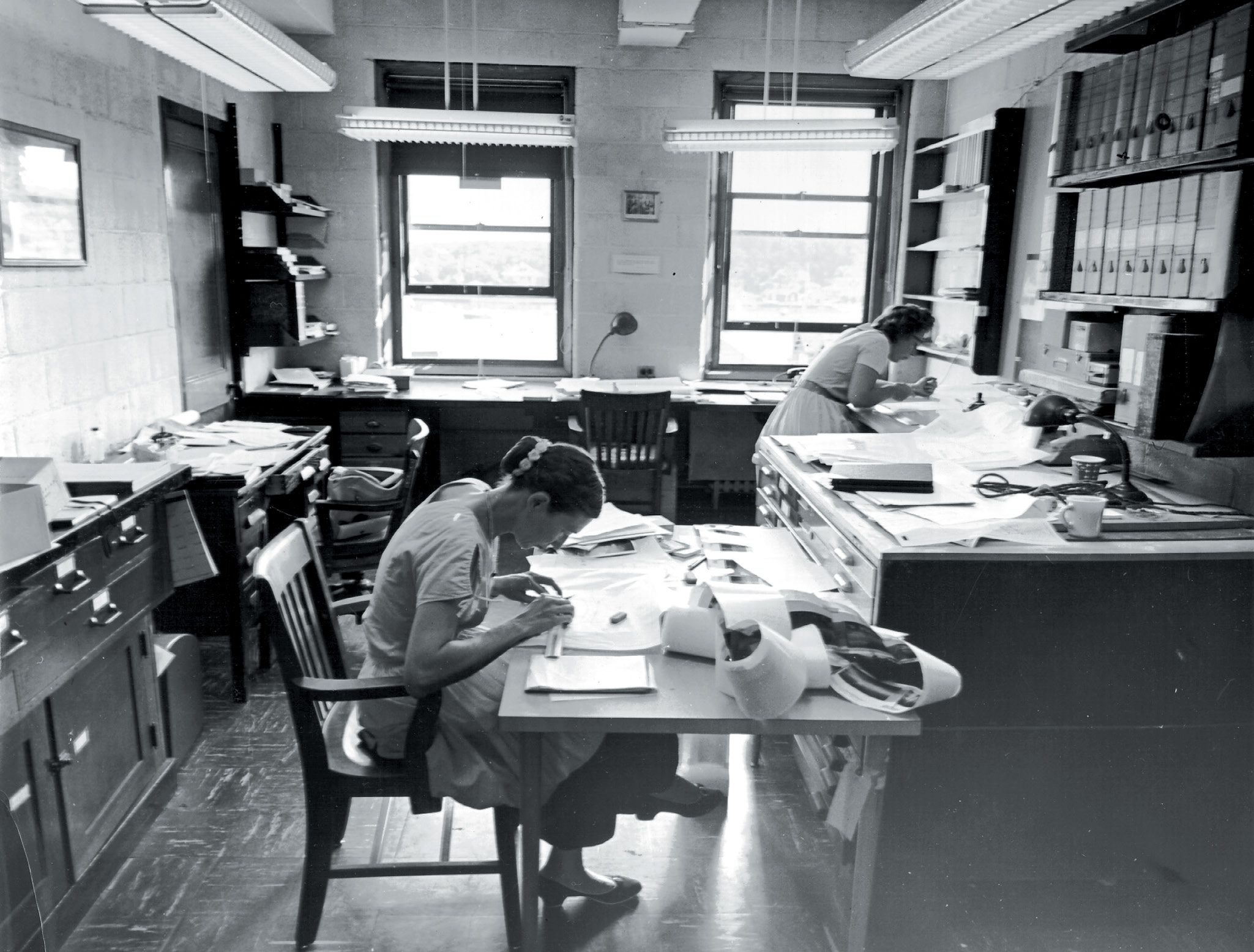

Joanne Simpson (foreground) in the 1950s examining images of clouds she took during flights over the Pacific Ocean.

SCHLESINGER LIBRARY/PUBLIC DOMAIN

“You have to be lovable to be loved,” her mother told Simpson as a child. That desire to be loved propelled Simpson through a painful life. She experienced sexual harassment at work and abusive relationships at home during her first two marriages before finding domestic peace in an enduring marriage to the hurricane expert Robert “Bob” Simpson. (She changed her name with each marriage, so Fleming refers to her as Joanne throughout the book.) She struggled with depression and migraines and was once fired midsemester when her department chair found out she was a woman. Through it all, she pursued meteorology with a fierce intensity. “Her work became a retreat from and recompense for all her personal problems,” Fleming writes.

And what significant work it was! During World War II, Simpson learned meteorology and then taught it to aviation cadets at the University of Chicago. Pursuing a PhD, she persevered despite being discouraged by most of the faculty until she took Herbert Riehl’s course on tropical meteorology. With Riehl as her graduate adviser, she developed a mathematical theory of entrainment in cumulus clouds and became the first woman to earn a doctorate in meteorology from a US university.

Simpson’s research took off, literally, at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution during the 1950s. Supported by the Office of Naval Research and later the National Hurricane Research Project, she began to fly on heavily instrumented aircraft through tropical clouds. The observations led her and Riehl to develop the concept of “hot towers,” or giant complexes of cumulonimbus clouds that provide the energy to power hurricanes and drive the tropical atmosphere.

Simpson’s studies of cloud dynamics and hurricanes led to her involvement with weather control experiments during the 1960s. Resigning from a full professorship at UCLA that she had held for only three years, Simpson went to work for the bureaucracy that would soon become NOAA. She and Bob eventually became leaders in Project Stormfury, a substantial effort by the US Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) and the US Navy to understand hurricanes and attempt to control them with cloud seeding. While that put them at the center of hurricane research, their desire to understand the storms meshed uncomfortably with the navy’s aspiration to control them for military advantage.

A much happier research environment came when Simpson became head of the Severe Storms Branch at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in 1979. There she improved cloud models and mentored young researchers. Her signature achievement was serving as project scientist for the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, a satellite that provided crucial data to understand climate change.

Because First Woman is primarily based on Simpson’s remarkable collection of personal papers, which are held at Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, she is the author of many of the words in the book. Fleming quotes at length from her personal journals, which contain intimate details about her scientific work and marital issues. He argues that Simpson chose not to place any restrictions on those diaries because of “her desire to be understood beyond her professional résumé.”

Fleming also uses two oral history interviews: one conducted by Simpson’s scientific colleague Margaret LeMone in 1989 and the other done by Kristine Harper, a historian of science, in 2000. The latter contains descriptions of what would now be recognized as extensive sexual harassment. For example, Simpson recalled that Riehl “tried to make a pass whenever he could, but I managed to resist just enough to keep him interested. And oh, we got to be really good friends and colleagues.”

Fleming uses biography to illuminate the broader history of tropical meteorology. Simpson’s career stretched from World War II into the 2000s, and her story sheds light on a field that Fleming argues has been neglected by historians in comparison to polar and temperate-latitude meteorology.

One inevitable cost to writing a concise book tightly focused on Simpson is that Fleming doesn’t compare her with peers, such as the radar meteorologist Pauline Morrow Austin and the atmospheric physicist Florence van Straten, who also had successful research careers. But neither woman was as celebrated as Simpson nor had her life as well documented. The continuing work of understanding women’s contributions to atmospheric science will certainly build on Fleming’s scholarship.

More about the authors

Roger Turner is the curator of instruments and artifacts at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia. His scholarly work focuses on the history of 20th-century atmospheric science.

Roger Turner, Science History Institute, Philadelphia.