Waves, whales, and cosmic neutrinos

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010055

Waves appear early in most university physics courses. Richard Feynman introduced them halfway through the first volume of his Lectures on Physics. And if I remember correctly, my first term at Imperial College, London, included a course on waves given by a plasma physicist named H. J. Pain.

The ubiquity and importance of wave phenomena account for their early pedagogical debut. Diffraction, interference, and other wave concepts help us understand the propagation not only of light and sound, but also of electrons in metals and plasma in the Sun’s corona.

But even though I’ve written many times about different kinds of waves, big and small, in solids, liquids, and gases, I was surprised to receive a press release from CERN linking neutrino oscillations and whale songs.

Neutrinos come in three flavors, which, in order of increasing mass, are electron, muon, and tau. In 1957 Bruno Pontecorvo predicted that neutrinos could spontaneously swap back and forth from one flavor to another. Neutrino oscillations were presumed to account for an apparent deficit of neutrinos from the Sun. In 2001 detectors housed deep in an old Canadian nickel mine confirmed

It turns out that the wavelength of neutrino oscillations is about the same as the wavelength of whale songs. That fortunate cosmic coincidence has led to a collaboration between particle physicists and biophysicists. To quote the CERN press release:

European astroparticle physicists are developing together KM3NeT, a large undersea neutrino telescope in the Mediterranean, dedicated to tracking neutrinos from astronomical sources. The deployment of deep sea neutrino detection lines for current experiments such as Antares in France, Nemo in Italy and Nestor in Greece has opened up the possibility of also installing monitoring devices for the permanent study of the deep sea environment: studies of ocean currents, of bioluminescence, of fauna and of seismic activity.

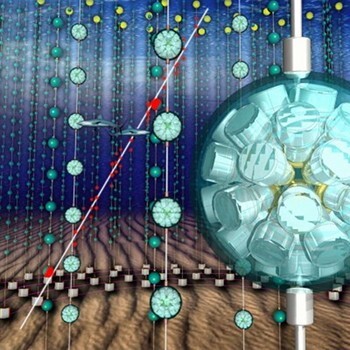

The accompanying cartoon shows what the KM3NeT detectors look like.

I couldn’t find any pictures of hydrophones, seismographs, and other instruments that will be deployed alongside the KM3NeT detectors, but hydrophones at a different undersea neutrino experiment

Wave phenomena are sufficiently rich and varied that professors who teach them don’t lack interesting, realworld examples. Still, it’s my recollection that Pain and most other lecturers relied on examples that were tried and true, rather than new and exciting. Now, 29 years after my freshman year, I know enough to find the connection between neutrinos and whales to be surprising. Then, back in Pain’s class, I’d have found it inspiring.