Turkey and Bose-Einstein condensates

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010053

Fred Dylla, the CEO of the American Institute of Physics, advocates roasting your Thanksgiving turkey at 533 K (500 °F, 260 °C). Charlie Burke, a food writer for the Heart of New England

High heat roasting (500 degrees) intensifies flavors and considerably shortens cooking time so there is less time for the white meat to dry out while the dark meat reaches proper temperature. We have found that fresh local turkey cooks in a surprisingly short time and has superior taste, although commercial turkeys are quite consistent in quality. It is important that the oven be clean, because excess smoke will be caused by any residue in the oven.

High-temperature roasting also makes sense physically. The higher the temperature, the steeper the temperature gradient is between the air inside the oven and the meat inside the turkey. Heat enters the turkey more effectively than at lower temperatures.

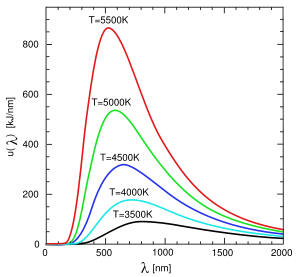

To the extent that an oven is like a blackbody radiator, high-temperature roasting brings another advantage. As the figure above shows, as you raise the temperature, you increase the number of photons available to cook the turkey.

Although it’s good for roasting turkeys, the blackbody spectrum’s dependence on temperature is bad for making a Bose–E instein condensate. As the archetypal bosons, blackbody photons should form a BEC. The trouble is, as Martin Weitz of the University of Bonn puts it in a paper

In such systems photons have a vanishing chemical potential, meaning that their number is not conserved when the temperature of the photon gas is varied; at low temperatures, photons disappear in the cavity walls instead of occupying the cavity ground state.

Weitz and his colleagues Jan Klaers, Julian Schmitt, and Frank Vewinger overcame that problem in an ingenious way. Their photon gas is not generated by an ovenlike cavity. Rather, they place a dye solution between two closely spaced concave mirrors and illuminate it with a laser.

Photons resonant with the mirrors’ separation bounce back and forth, but only after undergoing multiple scatterings off the dye molecules. The scatterings, which occur when the dye molecules are in an excited, laser-pumped state, are crucial because they ensure that photons interact weakly, not strongly, with each other, thereby satisfying a prerequisite for condensation.

The trapped photons have such a low effective mass that they condense at room temperature in the mirrors’ lowest accessible resonance. Weitz and his team bring about condensation when they increase the laser intensity, and therefore the density of scattered photons, above the critical value.

The left panel shows the photons just before the onset of condensation; the right panel shows a condensed central spot of photons condensed into a single macroscopic state (the mirrors’ TEM00 mode, to be precise).

I’m not sure whether Weitz, Klaers, Schmitt, and Vewinger ate Thanksgiving turkey today, hot-roasted or otherwise. But their coup de recherche is certainly cause for celebration. In the acknowledgments section of their paper they thank Jean Dalibard and Yvan Castin for discussions, the German Research Foundation for funding, and the Kastler Brossel Laboratory in Paris for hospitality.