The hunt for supersolidity

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010118

Superconductivity was discovered in 1911 when Heike Kamerlingh Onnes chilled a piece of solid mercury to 4.2 K and witnessed the resistivity of his sample vanish. Superfluidity was discovered in 1937 when Peter Kapitza and, independently, John Allen and Don Misener chilled helium-4 to 2.17 K and witnessed the viscosity of their respective samples vanish.

Both superconductivity and superfluidity owe their wondrous properties to the abrupt onset of a single collective ground state, a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC). Bosonic helium-4 atoms form a BEC directly. Electrons, being fermions, must first pair up.

Although Satyendra Bose’s and Albert Einstein’s BEC papers appeared 12 years before superfluidity was discovered, the state wasn’t anticipated by theorists—at least as far as I can tell. That’s not the case for the third and still-elusive superstate, supersolidity.

In 1970 Geoffrey Chester speculated

Because of their low mass and feeble interatomic interactions, helium atoms are so frisky at 0 K that low temperature alone is not enough to induce them to crystallize. Pressure must be applied, too. Even under pressure, helium-4 atoms might fail to line up to form a perfect solid. If that’s the case, Chester reasoned, the residual vacancies could form a BEC.

Four months after Chester’s paper appeared, Tony Leggett published a paper

Leggett’s analysis also identified a critical angular velocity ωc above which the BEC, though still mobile, would start to dissipate energy.

In 1981 David Bishop, Mikko Paalanen, and John Reppy implemented

The first hints of supersolidity

The hunt for what has become known as supersolidity got a boost in 2004 when Moses Chan and Eun-Seong Kim performed

Why Vycor? Chan and Kim thought that the pores’ extra surface area would promote the formation of defects and therefore increase the fraction of helium-4 atoms in the mobile BEC phase.

Chan and Kim detected a seemingly abrupt change in their vessel’s oscillating frequency at a temperature of 175 mK. The experiment did not, however, constitute the discovery of supersolidity. A change in frequency could indeed arise because of the appearance of a superfluid, although not necessarily of the kind envisioned by Chester. It could also arise because the crystal gains access to structural excitations that don’t move in lockstep with the bulk.

Those structural excitations would leave a telltale fingerprint—ωτ = 1 behavior—in the torsion oscillator data. The behavior is hardly super. Even Jello exhibits ωτ = 1 behavior. If the gelatin–water mixture is hot, a spoon passes through it easily, whereas if it’s cold, the spoon sticks to the surrounding Jello. Neither case presents much friction. But at some intermediate temperature, the mobile proteins, which embody Jello’s structural excitations, have a natural reaction time τ that perfectly balances the stirring frequency ω. The resulting resonance briefly makes stirring the Jello much harder.

Chan and Kim repeated their experiment on bulk helium-4 without the Vycor and found more or less the same result. Other groups confirmed that some sort of structural loosening takes place in solid helium-4, but the evidence did not converge on a single explanation, let alone on a BEC supersolid.

Indeed, helium-4’s apparent and partial loss of solidity at low temperature was looking less like the other BEC superstates, superconductivity and superfluidity, and more like a phenomenon, such as conductivity, which is caused by contaminants, dislocations, grain boundaries, phonons, and other features of crystalline materials.

In 2006 John Beamish and James Day performed

A SQUID and a magnet

The latest development in the hunt for supersolidity came last week in the form of a paper

They also hoped to find a single consistent explanation for Chan and Kim’s rotational anomaly, Beamish and Day’s shear modulus anomaly, and ωτ = 1 behavior.

Mapping the oscillator’s resonant frequency with enough accuracy to characterize the onset of NCRI required boosting experimental sensitivity. Chan and Kim had measured their oscillator’s change in resonant frequency Δf using a capacitive method. Each twist of their oscillator brought one plate of a capacitor close to the other plate, changing its capacitance as a function of time.

Davis and his team used a magnetic method. Each twist of their oscillator brought a samarium–cobalt magnet close to a SQUID magnetometer, which measured the resulting change in magnetic field. SQUIDs are exquisitely sensitive. Davis and his team could determine the oscillator’s rotational characteristics with four orders of magnitude more precision (per unit time) than Chan and Kim could.

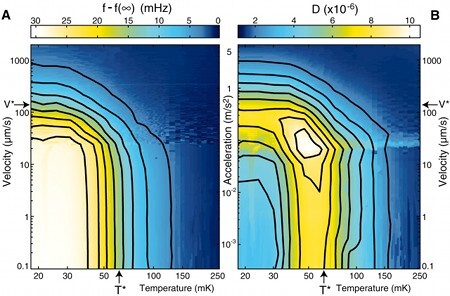

These figures taken from Davis’s Science paper show Δf and the dissipation factor D as functions of the speed of the cylindrical vessel and its temperature. Each figure is made up of 98 smoothly interpolated curves derived at different values of temperature. Two things stand out.

The findings of Davis and his team rule out a BEC as the source of NCRI. Instead, they demonstrate that crystal defects that display ωτ = 1 can provide a single explanation for rotational and shear anomalies. But, as Davis is careful to point out, the findings don’t exclude the possibility that a BEC supersolid could form. Moreover, although the findings constrain theories for what causes NCRI, they don’t identify its microscopic cause.

Superconductivity and superfluidity are dramatic effects that were discovered by people who weren’t looking for them. Having calculated that the fraction of superfluid BEC in a supersolid is small, Leggett concluded his 1970 paper by observing

it seems highly unlikely that these effects would have been discovered by accident even if “superfluid solids” do exist at attained temperatures.

After three decades, supersolidity remains undiscovered, by accident or otherwise.