The confounding magnetic readings of Voyager 1

One of the Voyager probes drifts through interstellar space in this illustration.

NASA/JPL

In December 2012, a group of space scientists gathered in San Francisco to hold a vote. The lone issue on the ballot: Is Voyager 1 in, or is it out?

Throughout that year, the hardy spacecraft had beamed back tantalizing hints that it had left the heliosphere, the magnetic bubble inflated by the solar wind, and become the first human-made object to enter interstellar space. Yet mission scientists weren’t seeing what they had thought would be the unambiguous signature of Voyager‘s departure: a sudden shift in direction of the magnetic field. It seemed inconceivable that the probe could have left a river of charged particles flowing from the Sun for an ocean of interstellar plasma without drastic magnetic deviations. “That was truly a shock to all of us,” says Len Burlaga, coinvestigator of the magnetometer instrument. “We figured that in a completely different region [the field direction] wouldn’t be the same.”

Subsequent measurements from the probe’s other instruments ultimately provided enough evidence to convince most of the voters in San Francisco that Voyager 1 had crossed into interstellar space in August 2012, some 122 AU from the Sun (see Physics Today, November 2013, page 18

“Boundaries are simple when you learn about them in books,” says Merav Opher

The first hint of Voyager 1‘s heliopause crossing came on 28 July 2012, when galactic cosmic-ray intensity abruptly jumped, the concentration of solar particles plummeted, and the magnetic field intensity doubled, to about 0.4 nT. Four more inflection points occurred over the next month, marked by a fall in field intensity, then a jump, then a fall, and one last jump on 25 August, the currently accepted interstellar crossing date. Yet during those turbulent four weeks, the direction of the magnetic field barely budged. The big Science paper

Voyager 1 detected changes in magnetic field intensity (top graph) five separate times (B1–B5), presumably as it crossed the heliopause, in mid 2012. But the magnetic field direction, measured here in terms of azimuthal and elevation angle, remained steady.

L. F. Burlaga, N. F. Ness, and E. C. Stone, Science 2013

With the benefit of hindsight, Opher and several of her colleagues now say they shouldn’t have been surprised at the magnetic complexity relayed by the interstellar probe. After all, the heliopause is not a static boundary. Interstellar magnetic fields likely pile up and drape about the solar bubble, which could result in elevated field intensity and twists in field direction. Some of those field lines could break and reconnect in new orientations (see Physics Today, February 2019, page 20

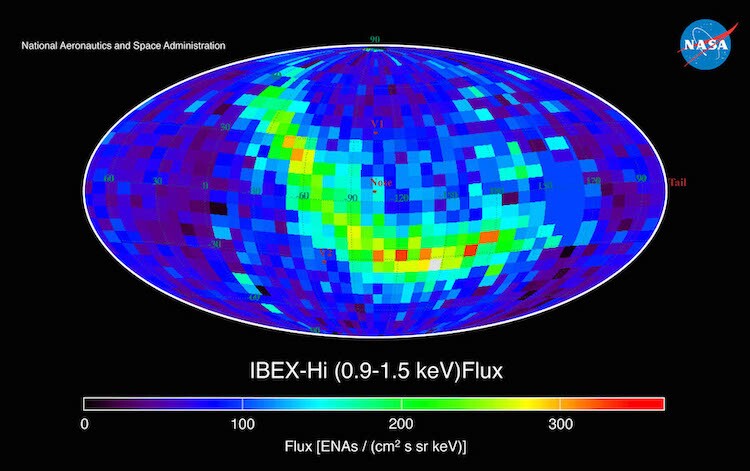

Another complication is that although the interstellar magnetic field direction almost certainly differs from the heliosphere’s, it’s unclear what that direction should be. Voyager 1 is humanity’s first beacon in interstellar waters—all other clues have come indirectly. One important line of evidence comes from the Interstellar Boundary Explorer

The Interstellar Boundary Explorer spacecraft detected a bright flux of neutral atoms in a ribbon shape near the nose of the heliosphere. The positions of the Voyager probes (V1 and V2) are shown in relation to that of the ribbon.

D. J. McComas et al., Science

Theorists are analyzing Voyager 1‘s measurements in attempts to combine all those hints and hypotheses into workable models. In late 2013, Opher and colleague James Drake ran magnetohydrodynamic simulations of the heliosphere environment and found that interstellar magnetic field lines twist

Nathan Schwadron

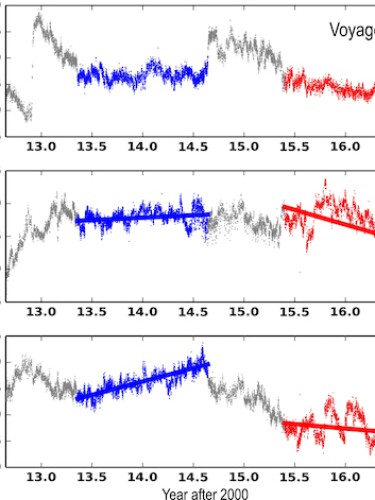

But by the time Schwadron’s paper

In mid 2013 Voyager 1 detected a shift in the magnetic field toward the IBEX ribbon (blue trend line). But in 2015 the direction changed (red).

N. A. Schwadron and D. J. McComas, Astrophys. J. 2017

Though most researchers are focused on adjusting their models to fit the new measurements, a small but vocal minority maintain that Voyager 1‘s magnetic readings demonstrate that the probe is still in the heliosphere. Voyager scientists George Gloeckler

After several years of scratching heads and tuning models, those who have been following the two Voyager spacecraft’s exploits are now focused solely on the first interstellar magnetic results for Voyager 2, which are expected to be released at next week’s conference in Pasadena. Opher and Schwadron expect little to no change in the field direction, just as with Voyager 1. Burlaga and McComas expect a more significant shift, based on the hypothesis that the draping of the interstellar field should be different in Voyager 2‘s neck of the woods.

Regardless of who’s right (an abstract

More about the authors

Andrew Grant, agrant@aip.org