Should we get excited about yet more exoplanets?

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010078

On my drive to work I pass the Washington Times‘s printing and distribution center on New York Avenue. This morning the large illuminated sign on the building alerted passing motorists about NASA’s latest discovery: extrasolar planets that occupy the “habitable” zone around their respective stars.

Earlier this week, I’d received press releases from NASA and the University of California, Santa Cruz, so I knew about the news. But as I drove past the Times sign, I wondered how other commuters would react. Would they be excited?

The first extrasolar planet orbiting a main-sequence star, 51 Pegasi b

The message on the Times sign was too brief to describe what I think is the full import of the latest exoplanet discovery: NASA’s Kepler mission is stunningly successful at finding extrasolar planets.

For nearly two years since its launch, Kepler has been staring at a patch of sky that includes the constellations of Cygnus, Draco, and Lyra. Of the stars within that field of view, 156 000 are monitored continuously for the telltale dips that occur when planets pass in front of them.

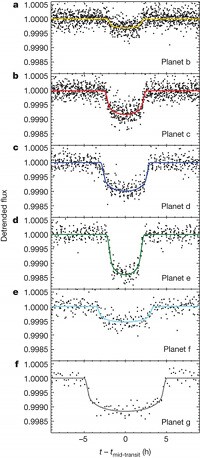

The figure on the right shows dips in the starlight from just one planetary system, Kepler-11. Each of the six dips arises from a different planet. The discovery of a six-planet system was remarkable enough that it merited its own paper in Nature

As for planets in the habitable zone—that is, the volume where starlight is strong enough to prevent water from permanently freezing and weak enough to prevent it from permanently vaporizing—t hey are among the 1235 possible planets found in the first publicly released set of Kepler data. To quote the NASA press release:

Of these, 68 are approximately Earth-size; 288 are super-Earth-size; 662 are Neptune-size; 165 are the size of Jupiter and 19 are larger than Jupiter.

Of the 54 new planet candidates found in the habitable zone, five are near Earth-sized. The remaining 49 habitable zone candidates range from super-Earth size—up to twice the size of Earth—to larger than Jupiter.

Should we get excited by those candidates? Yes!—but with a possible caveat. As an editorial

A truly Earth-like planet could harbor Earth-like life and could one day become a colony for humans. On the other hand, any of the planets that Kepler has found within habitable zones could turn out to support life not as we know it—which in my view would be more interesting than finding, say, extrasolar Escherichia coli.