Rocks and bones

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010141

The availability of scientific papers online makes it easier not only to find the latest research but also to trace back through time a paper’s academic ancestry, which may or may not lie in the same field. That boon to the curious came to mind this morning when I encountered a paper in JASA Express Letters.

The paper

Cancellous bone, in case you didn’t know, is the spongy type of osseous tissue that constitutes the inside parts of long bones, especially at the ends, and of vertebrae. Cortical bone is the other type of osseous tissue. It provides cancellous bone with a solid casing and constitutes the inside and outside of small bones.

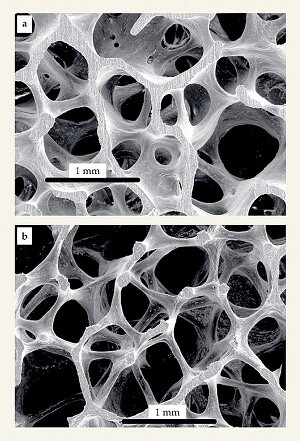

Both types osseous tissue regenerate at their surfaces, but because of its porous structure, cancellous bone is more readily weakened than is cortical bone when regeneration fails to keep up with wear and tear. The two images show samples of cancellous bone taken from vertebrae. The top one comes from a 21-year-old man; the bottom one comes from a 65-year-old woman.*

Mizuno and his colleagues are trying to develop an ultrasound-based method for assessing the condition of bones. Although doctors already have methods based on x rays at their disposal, an ultrasound diagnostic would likely be cheaper and more convenient.

Water-saturated rocks

Not knowing much about the propagation of ultrasound in bones, I was surprised to learn from the antecedents to Mizuno’s paper that his line of research springs, in part, from a paper about water-saturated rocks. In 1956 Maurice Biot published a theoretical description

At that time Biot worked for an oil company. I’m not sure whether his paper helped anyone to find oil deposits. It did, however, help to establish the field of poromechanics. It also predicted that porous, fluid-filled media support two distinct compressional waves: the normal shear wave and a so-called slow wave that arises from refraction and mode conversion at the solid–fluid boundaries.

Biot’s prediction was verified

Judging by the papers that Mizuno and his coauthors cite, it took another two decades before anyone recognized the relevance of Biot’s slow wave to bone tissue. In 1995 Atsushi Hosokawa and Takahiko Otani detected

Before Biot’s theory can be turned into an in vivo diagnostic, more research is needed into how ultrasound propagates in whole, intact bones, whose structure is not isotropic, as Biot’s theory presumes. Mizuno and his collaborators took a further step in that direction by examining a sample of cancellous bone that retained its casing of cortical bone.

Having learned something of Biot’s theory, I became curious about the man himself. If you are too, you can read about his distinguished career in his obituary

* The images come from “Plasticity and toughness in bone,” an article