Physics in the Great Depression

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010315

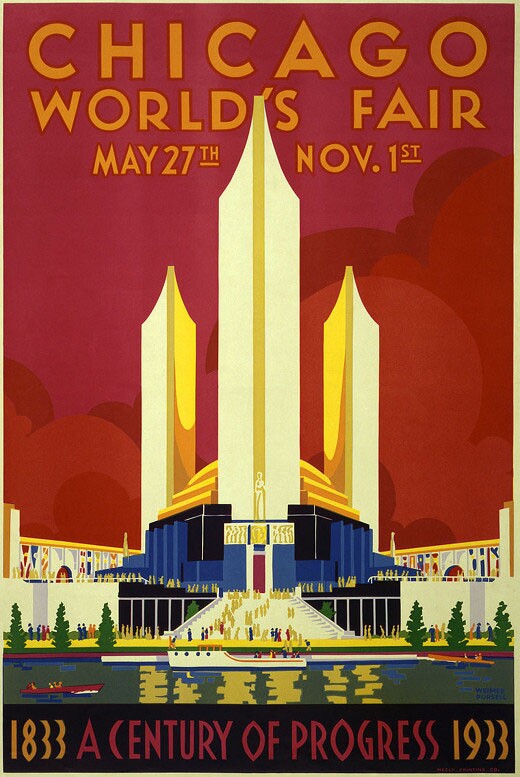

In 1933, during one of the worst years of the Great Depression, the city of Chicago celebrated its first 100 years by hosting the World’s Fair. One of the fair’s attractions was the Hall of Science. In a speech dedicating the hall, the head of Bell Labs, Frank Jewett, broke from the festive mood to sound this note of alarm:

In some quarters a senseless fear of science seems to have taken hold. We hear the cry that there should be a holiday in scientific research and in the new applications of science, or that there should be a forced stoppage in the extension of old usages by mandatory legislation.

Jewett’s foreboding was likely unsurprising to his audience, but it shocked me when I encountered it in the pages of Physics Today. The quote appears in Charles Weiner’s October 1970 feature article “Physics in the Great Depression

Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1931, Weiner was a historian of science, whose research focused on science’s political, social, and ethical dimensions. At the time he wrote the Physics Today article, he directed the Center for History of Physics

In the article, Weiner recounted the optimism of US physicists in the 1920s. Thanks to the National Research Fellowships program, which was set up in 1919, young researchers could study at Cambridge, Göttingen, and other major European centers of physics. Irving Langmuir, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Edward Condon were among the beneficiaries. Private foundations, notably the Rockefeller-supported General Education Board, donated millions of dollars to develop science departments at US universities.

Weiner Pursell designed this silkscreen print for Neely Printing Co of Chicago.

CREDIT: Library of Congress

The Great Depression hit US physicists hard. Salaries were cut, research funding withered, and newly graduated PhDs could barely find work that took full advantage of their education. In his report for the academic year 1934–35, the head of the physics department at the University of Illinois, F. Wheeler Loomis recorded the following:

It is almost impossible to convey an adequate idea of the extent to which our work, both in teaching and research, has been hampered and made inefficient and how all progress has been blocked by the inability to buy necessary articles.

If physicists and other scientists were suffering along with the general population, where did the antiscience sentiment that Jewett decried spring from?

Modern unease with science did not begin with the Great Depression. Poison gas, machine guns, submarines, and the other technological weapons of World War I stoked a “stop science” movement in 1920s Britain, which, in Weiner’s words, “found increased social resonance in the US in the 1930’s.”

Aware of the antiscience threat, the US physics establishment promoted the role of science and technology in economic progress. But given that scientific progress had evidently failed to forestall the Depression, the public was unconvinced. Worse, as Weiner put it, “scientists did not respond adequately to the public’s fear that uncontrolled and misapplied technology caused human misery.”

Weiner began his article by tying the Depression of the 1930s to what he called the “soul-searching seventies.” According to his diagnosis, the US physics community of the 1970s faced a “long-range threat of reduced research funds, slackening employment opportunities, and lower public esteem for physics.” As the US continues its slow recovery from the Great Recession, what lessons can we draw from the Great Depression?

Worth defending

To answer my own question, I think physicists should not follow the example of their 1930s predecessors and oversell the case that funding basic research is a path to economic prosperity. For one thing, the payoffs of basic research are uncertain and often distant. The first clinically useful magnetic resonance image was obtained by John Mallard of the University of Aberdeen in 1980, 36 years after I. I. Rabi’s discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance. Peter Kapitsa, John Allen, and Don Misener discovered superfluidity in 1937. The phenomenon awaits its first commercial application.

And even when basic research begets useful technology sooner, researchers and their employers may not be the ones to reap the largest financial rewards. Giant magnetoresistance was discovered in 1988 by Albert Fert in France and, independently, by Peter Grünberg in West Germany. Nine years later, the first GMR-based read heads for disk drives were brought to market by IBM, a US company.

Lastly, there’s the weak link between a country’s investment in R&D

Physicists should still proudly point to transistors, lasers, LEDs, and other fruits of their basic research when they speak to the public and to politicians. But they should, as astronomers do, also emphasize the cultural benefits of basic research. The physics of superfluidity is worth funding because it is rich, complex, and fascinating.

In 1969 the director of Fermilab, Robert Wilson, testified before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy of the US Congress. Asked by Senator John Pastore (D-RI) what Fermilab’s Tevatron collider might contribute to US security, Wilson’s first reply was “Nothing at all.” When Pastore pressed him further and asked if the collider might help the US compete with the Soviet Union, he replied:

Only from a long-range point of view, of a developing technology. Otherwise, it has to do with: Are we good painters, good sculptors, great poets? I mean all the things we really venerate and honor in our country and are patriotic about. In that sense, it has nothing to do directly with defending our country, except to make it worth defending.

The exchange between Pastore and Wilson is quoted at greater length in the obituary