Photoreceptors, carburetors, and intelligent design

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010035

A paper

Now you might think, as I did before reading the paper, that the problem had already been solved. Our retinas contain three types of photoreceptive neuron that are maximally sensitive to red, green, or blue light. When, say, the blue photoreceptors fire, we see blue, right? Wrong.

It turns out that neuroscientists have known for some time that our brains don’t receive direct signals from the R, G, and B photoreceptors. That’s in part because the photoreceptors’ spectral responses overlap. A dim red light would elicit the same level of response in an R photoreceptor as a bright red light would elicit in a G photoreceptor.

Our eyes rely instead on “opponency.” The signals that run from our retinas to our brains correspond to two opposing combinations: B − (R + G) and R − G. The combinations are calculated by specialized neurons called ganglions that receive input from mixed groups of photoreceptors.

Chichilnisky and his team connected hundreds of ganglion cells in vitro to electrodes. They then recorded the cells’ response to a spectrally varying light field whose spatial resolution was fine enough to trigger responses in individual photoreceptors.

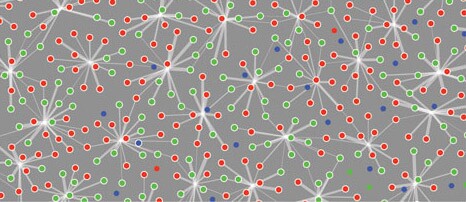

The figure shows schematically how the photoreceptors (colored dots) are grouped to feed data to individual ganglions (at the focal points of the white lines). In principle, the grouping of randomly distributed photoreceptors could account for the retina’s sensitivity to color. But Chichilnisky found that an extra ingredient is needed: The photoreceptors closest to the focal points are weighted more heavily than those farther out.

Sensing color with randomly distributed and simply connected R, G, and B photoreceptors seems elegant, but if you look under the hood at the proteins responsible, you see a baroque edifice of bizarre complexity. Here, for you to skip, skim, or scrutinize, is how the Wikipedia entry on photoreceptors

Evolution and the limits of what can be achieved within cells with proteins are behind the rather involved transduction chain. To achieve its current performance, the primate eye has made use of a succession of incremental changes that began in the Cambrian era 540 million years ago.

Human engineers aren’t limited to making only incremental changes. My first car, a 1977 Chevrolet Malibu

The fuel injector didn’t evolve from the carburetor, nor did the transistor evolve from the thermionic valve. Both innovations, which are simpler and more effective than their predecessors, resulted from leaps of engineering and scientific imagination—which brings me, at last, to my main point.

The devices in our bodies are intricate and complex, but they’re too fussy to be the work of an intelligent designer.