My computational education

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010194

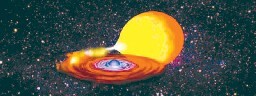

I peaked as a computational scientist in 1986. At that time, two years from finishing my PhD, I was trying to account for an aspect of the x-ray emission from a pulsar known as Hercules X-1, the first x-ray source discovered in the constellation Hercules. Hercules X-1 consists of a normal star and a rapidly spinning neutron star. So close are the two stars to each other that the neutron star’s gravity grabs material from the normal star’s outer atmosphere. By the time the purloined material reaches the neutron star, it’s a million-degree, x-ray-emitting plasma.

Every 1.7 days—a number I can’t forget!—the two stars orbit their mutual center of mass, and, if you’re watching from Earth, the neutron star is eclipsed by its companion. But just before and just after total eclipse, the neutron star’s x rays pass through the companion’s atmosphere. From a plot of x-ray emission versus time, you can probe and explain the atmosphere’s vertical structure—with the help of a computer model, that is.

Artist’s impression of an x-ray binary system from NASA’s Imagine the Universe!

Artist’s impression of an x-ray binary system from NASA’s Imagine the Universe!

And so, over several months, I created my longest-ever computer program. Excluding comments, it ran to more than 120 lines of Digital Equipment’s proprietary flavor of Fortran 77. Fortunately, I didn’t have to create a data analysis program from scratch—a postdoc had done that before me—but I did have to incorporate my model into his code. (See Dianne O’Leary’s “Computational software: Writing your legacy,” Computing in Science & Engineering, January/February 2006, page 78

How did I become a programmer? When I started graduate school I had no programming—or even computer—experience. To me, computers were toys for the uncool boys. But then my university offered its graduate students a course in scientific programming. And I took it.

The teacher, whose research was in the field of artificial intelligence, displayed impressive loyalty to a single ancient T-shirt. In class and around town, he’d pad about without shoes or socks like a hobbit. His course briefly touched on programming techniques, but only in the abstract. My real teachers were the postdocs in my group. They taught me a sprinkling of practical tricks and, perhaps more useful, some sound principles of programming practice.

Those learning experiences popped into my head when I read Francis Sullivan’s column about Sudoku (“Born to compute,” Computing in Science & Engineering, July/August 2006, page 88

Having solved the physics for my model, I had to implement it on a computer—which meant I had to read arcane computing manuals, swat the bugs I’d introduced into my program, and struggle with fussy compilers. Every now and again, amid the toil and frustration, would come flashes of inspiration and progress. In the end, I grew to like programming.

So if you teach computational science and your class includes compute-free students like me, give them an interesting science or engineering problem to solve. The poor things might be driven to program despite their genetic inheritance.

This essay by Charles Day first appeared