Molecules to materials

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010085

I was happy the other day to receive a thick, info-packed newsletter from Tohoku University’s Advanced Institute for Materials Research

The newsletter’s title, “Molecules to Materials,” succinctly and accurately describes one of AIMR’s aims. It also got me thinking.

The notion of making materials from molecules isn’t new. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Nottingham University’s Frederick Kipping developed a family of polymerized siloxanes, which he called silicone.

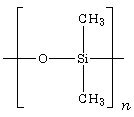

Silicone consists of crosslinked chains of alternating silicon and oxygen atoms. Attached to each silicon atom are two alkyl groups, such as methyl shown here.

The methyl groups mediate the crosslinking. By altering the length of the chains and the type of methyl group, Kipping and his successors have created a huge range of silicone materials—from free-flowing liquids to hard, stiff resins, all of which share siloxane’s resistance to UV degradation and corrosion, low toxicity, and low coefficient of friction. My wife has a silicone madeleine

Superhybrid materials

Following Kipping’s example, chemists, material scientists, and physicists at AIMR and elsewhere are trying to make molecular materials that have useful properties. In principle, molecules are versatile building blocks. Chemical substitutions can tailor both a molecule’s properties and how the molecule binds to other molecules.

Making molecular material that does what you want is tricky. The bonds that hold the molecules to each other can alter the molecules’ properties. And even if you can identify a molecular arrangement that yields the properties you want, there’s no guarantee that the resultant material is either robust or makable.

AIMR’s Tadafumi Adschiri has devised a clever way to fabricate molecular materials. Like other researchers, he assembles his materials from nanoparticles whose size and chemistry have been picked to yield a material with a particular set of properties. And as Kipping was, he’s interested in combining inorganic and organic molecules into hybrid polymeric materials.

To both make the nanoparticles and combine them with polymers, Adschiri uses supercritical fluids as solvents. Above its critical point—that is, the temperature and pressure at which liquid and gas phases coexist—a substance becomes a much better solvent. Supercritical carbon dioxide, for example, will readily dissolve caffeine, hence its use in the fanciest and most effective method of decaffeination.

Fluids that are immiscible below the critical point will readily mix when they’re both supercritical. Adschiri exploits that feature to combine inorganic nanoparticles, whose ingredients dissolve in subcritical water, with organic nanoparticles and polymers, whose ingredients dissolve in subcritical oil.

Among the “superhybrid materials” that Adschiri makes with his supercritical process is a film that conducts heat but not electricity and the flexible, high-refractive-index film shown here.

The info-backed newsletter that inspired me to write this post opens with a message from AIMR’s director, Yoshinori Yamamoto, entitled “Green Materials.” Yamamoto wants his institute to be in the forefront of developing new materials for energy harvesting, energy saving, and environmental cleanup.

Of course, it’s better if you don’t have to clean up the environment in the first place. By using supercritical water and oil, Adschiri greenly avoids using environmentally hostile organic solvents.