Is weak measurement more than an experimental tool?

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010138

“You cannot measure a quantum particle without disturbing it. Or can you? Weird ‘weak measurements’ are opening new vistas in quantum physics.”

Thus reads the dek that tops Adrian Cho’s excellent news story

My first encounter with weak measurement came in 2008 when I wrote

The separation that Hosten and Kwiat sought was just 70 nm. To measure it, they adapted Vaidman, Aharonov, and Albert’s weak measurement approach, which I introduced in the following way:

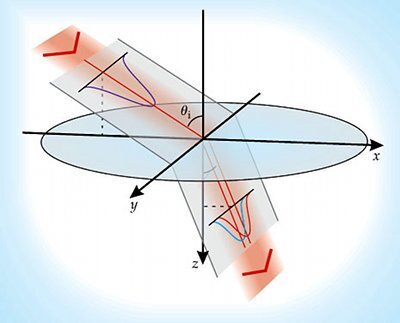

The three theorists considered the case of a Stern–Gerlach experiment whose beams and magnets are too weak to segregate up and down spins. Ordinarily, such a setup would yield not the two well-separated spots of Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach’s famous experiment but a peanut-shaped blob.

That unhappy situation would change, the three theorists argued, if you used two polarizing filters placed before and after the magnets. Orienting the filters’ axes at 90∞ would cut off all transmission, of course. But setting them just off perpendicular would have a surprising effect: The wavefunctions of those few atoms that made it through would interfere and boost the spin-dependent displacement by orders of magnitude.

Weak measurement does not provide a free lunch, however. In graphical terms, it pushes a peaked signal further away from the origin, making its displacement easier to determine. But the technique also reduces the peak’s amplitude, making it harder to see anything at all. If an experiment’s resolution is limited only by the statistics of photon counting, the two effects cancel. That was far from the case for Hosten and Kwiat’s experiment, in which systematic errors, not a paucity of photons, limited resolution.

My story was about the spin Hall effect of light, not weak measurement. Indeed, if Hosten and Kwiat had been able to overcome jitter in their laser’s pointing direction, wobbles in the optical table, and other sources of blur, they need not have used weak measurement at all. Moreover, the experiment can be analyzed using the 19th-century physics of Augustin-Jean Fresnel and James Clerk Maxwell.

But as Adrian recounts in his story, weak measurement could be more than just a useful tool for determining small values. By barely perturbing a particle’s wavefunction—at least during the weak interaction phase—weak measurement appears to provide a means of circumventing quantum mechanics’ prohibition on tracking individual particles as they fly through an interferometer.

What’s more, in a feature article

Not surprisingly, weak measurement as an interpretation of quantum mechanics has proven controversial. Aharonov, Popescu, and Tollaksen’s article provoked four letters

It’s difficult for a nonexpert like me to evaluate the broader claims of weak measurement. For one thing, Aharonov, Popescu, and Tollaksen assert that their interpretation is “completely equivalent to standard quantum mechanics in so far as their predictions are concerned.” And some of the arguments, pro and con, hinge on interpretation, rather than experimentally determined facts or unimpeachable mathematical analysis.

Aharonov, Popescu, and Tollaksen suggest that their time-symmetric formulation of quantum mechanics could readily accommodate new, as-yet undiscovered physics. Even if that doesn’t turn out to be the case, it’s beyond dispute that weak measurement has proven useful in the lab.