Inspiring the next generation of Hispanic American physicists

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010119

Attracting Hispanic voters is a challenge for both major political parties in the US. Republican candidates struggle because of the anti-immigrant positions taken by some of their party’s most prominent members, including the governors of Arizona and Georgia. Democratic candidates worry that low turnout at elections will nullify the advantage their party currently enjoys among Hispanic voters.

Despite the challenges, you can be sure that political strategists will not ignore Hispanic voters. The US Census Bureau predicts that the percentage of Hispanics in the US population will grow from the 15.5% it is now to 20.1% in 2030 and to 24.4% in 2050. During the last presidential election campaign, Barack Obama and John McCain both ran Spanish-language TV ads.

According to the Statistical Research Center of the American Institute of Physics, the percentage of physics bachelor’s degrees awarded to Hispanic Americans has been stuck around 3.5% since 2001. Given the size of the US Hispanic population, that small fraction corresponds to an embarrassingly large number of schoolchildren who, for one reason or another, are choosing not to pursue physics.

Why aren’t more Hispanic children attracted to physics? One possible answer appeared in Physics Today‘s September 1991 issue. Having recently watched the grisly movie The Silence of the Lambs, C. J. Salgado of Los Alamos, New Mexico, wrote a letter

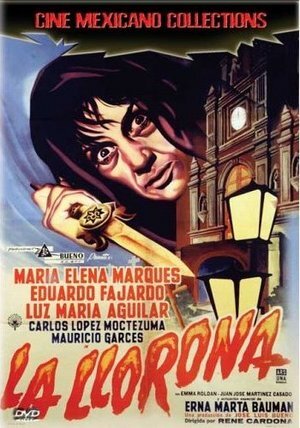

In his letter, Salgado evocatively described scenes from his East Los Angeles childhood and from the summer he spent at his grandfather’s ranch, Xaratanga, in Western Mexico. He also recalled being warned by his grandmother not to wander off at night lest he be abducted by La Llorona

For Salgado, La Llorona symbolized a culture of superstition and ignorance:

When our children ask about our world, they are misled, ignored or told to be silent. Why so much fear? Is it based on reality, or are we hiding from spirits? Science has got to come out into the open in our homes if our children are to partake of its opportunities for happiness and success.

I couldn’t tell from Salgado’s letter whether he taught physics or engaged in public outreach. He ends his letter not with a detailed prescription, but with a call to action:

Let’s be strong and face up to our fears of the unknown. Let’s talk. The night is not so forbidden. Any child will tell you that there are things to see in the dark, for children have curiosity and imagination that light their way like the moonbeams of Xaratanga. We can all learn from them. The cover-up must end—else our children will remain like the lamb, quiet and still.