Infrared neural stimulation at Photonics West

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010159

In 2005 Vanderbilt University’s Anita Mahadevan-Jansen and her colleagues made a remarkable discovery: Pulsed IR light triggers a tightly localized response in mammalian peripheral nerves. What’s more, the pulse energy needed is far below the threshold for damaging tissue.

Mahadevan-Jansen’s team had found, to quote from the abstract of the discovery paper

The mechanism behind INS is thermal. In a series of experiments published

Unlike electrical stimulation, which requires electrodes to be inserted to tissue, INS can be delivered without contact. Given the compact size of solid-state light sources, INS-based cochlear implants, pace makers, and other medical devices are conceivable—at least in principle.

From PNS to CNS

At this year’s SPIE Photonics West

The focus of Roe’s talk was on her team’s use of both functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and optical imaging to map the cerebral cortex of macaque and squirrel monkeys. The cerebral cortex, which forms the outer part of the mammalian brain, is important for several high-level functions including attention, memory, and language. Research has shown that specific functions are controlled by clusters of nerves that occupy distinct domains about 200 μm across.

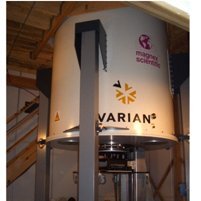

The fMRI scans can pinpoint which regions of the brain become active in response to a stimulus, such as a blinking light, a burst of noise, or even—in the case of human subjects—a verbal suggestion. The technique works because brain cells, when called into action, require energy, which they obtain, in part, from a sudden inrush of oxygenated blood. Oxygenated hemoglobin, being less magnetic than deoxygenated hemoglobin, shows up in fMRI. Roe’s lab is one of the few in he world that has an MRI scanner (shown here) whose bore is of a suitable size and orientation for monkey studies.

Oxygenated hemoglobin is also redder and brighter than deoxygenated hemoglobin. The sudden inrush of blood to a region of the brain is also visible—literally—if the region under investigation is exposed and close to the surface. The difference in red brightness is not difficult to detect. Roe’s lab uses a red laser and a commercial CCD camera.

It’s more difficult to expose an area of the monkey’s cerebral cortex to visualize those changes in oxygenation. To meet that goal, Roe and her collaborators surgically implanted an optical window in the monkey’s skull, a procedure involving replacement of a section of the skull and native dura (the protective membrane surrounding the brain) with a circular chamber and a biocompatible transparent, artificial dura. Besides providing a way to view the cerebral cortex, the window also allows an INS signal to be delivered.

At this stage of their research, Roe and her team have succeeded in associating some brain functions, like attention, with cortical domains. They have observed the telltale reddening of the domains when the monkeys are called on to perform a task. And they have confirmed, as her colleague Mahadevan-Jansen has done for the peripheral nervous system, that INS does not cause visible, lasting damage to tissue.

What remains to be demonstrated is whether INS can potentially be used to achieve therapeutic effects in the central nervous system. Enhancing or restoring lost function is one possibility. At the end of her talk, Roe speculated that some symptoms of autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder might one day be treatable with INS.