Informing decisions, dispelling skeptics

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010166

Yesterday afternoon I visited the Marian Koshland Science Museum

“Exhibit” might suggest objects. In fact, Life Lab consists solely of large electronic touch screens. As visitors progress through the exhibit, they interact with the screens. In the process, they learn about the biology of aging. One big screen, coupled to a motion sensor, displays a butterfly-catching game. When you move your arms, your avatar does too. Your goal is to catch animated butterflies that flit by. As you play through the game’s three rounds, your avatar ages—that is, her limbs become less agile and her reflexes less sharp. You catch fewer butterflies.

Other screens take you on a self-guided tour of the brain as viewed by magnetic resonance imaging and fluorescently tagged proteins. Another screen teaches you, through a game-like interface, how your genetic inheritance, your economic situation, and your lifestyle choices affect your brain’s development and health. One of the exhibit’s aims is to teach healthy habits.

Using screens to convey information is effective—and appropriate. After all, the end product of scientific investigations is knowledge. On the other hand, the lack of tangible objects left me wondering whether the exhibit needed a physical home at all. Turning it into an iPad app seemed like an obvious next step. Indeed, Erika Shugart, the exhibit’s project manager and the museum’s deputy director, told me that creating an app is at least a hope, if not a goal.

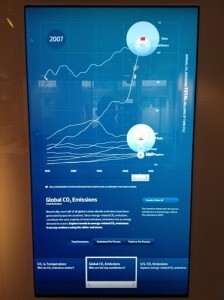

After my encounter with Life Lab, I spent some time exploring another Koshland exhibit, Earth Lab: Degrees of Change. Like Life Lab, the global warming exhibit features touch screens. On one of them (shown here) I could watch the carbon emissions of the US, China, Russia, and other countries rise through recent history. Another screen challenges you to meet a carbon emissions target by applying various priorities and implementing various policies.

I asked Johann Yurgen, the museum’s operations and visitor services manager, if climate change deniers ever tour the global warming exhibit. “Yes,” he said. And then he recounted the visit of a man from Denver who was so outraged by the exhibit that he demanded the return of his $7 admission fee. “It’s lies!” the Denverite declared.

Yurgen offered to walk the man through the exhibit. What struck the visitor the most on that personal tour—and what changed his mind about climate change—was one of the exhibit’s few artifacts: a section of the trunk of a 500-year-old tree. Embodied in the changing width of the trunk’s rings was a physical record of Earth’s changing climate.

Given our limited lifespans and the natural interannual fluctuations in Earth’s climate, climate change is not perceptible to most people. It’s therefore easy to dismiss as a theory. But as global temperatures steadily rise, the world’s collection of physical evidence—the retreating glaciers, the rising seas, and so on—grows too.

Eventually, the evidence in favor of anthropogenic global warming will become overwhelming. Whether humans intervene to mitigate climate change before that point is reached will depend, in part, on the efforts of the Koshland Museum and other bodies that inform the public about the science of climate change.