In praise of flocking

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010239

Indian restaurants in 1970s Britain, especially those in the provinces, seemed to follow the same template. Menus were standardized around a few curries, among them mild creamy Korma, chili-red Rogan Josh, and formidably spiced Vindaloo. And on the walls, more often than not, you’d see red velvet flocked wallpaper.

Rolls of red velvet flocked wallpaper.

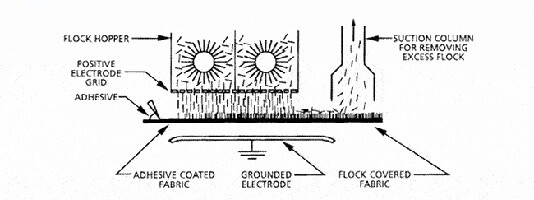

Flocking is a generic process for creating a tufted surface in which short fibers are affixed to a substrate. In the case of wallpaper, the flocked regions form an intricate repeating pattern that suggests opulence. Helpfully for a restaurant, the tufts also absorb sound.

Why am I telling you about vintage restaurant decor? Because earlier this year I made a promise to a fan of Physics Today‘s Facebook page

Fortunately, finding something to say about flocking and physics did not prove to be challenging. From the American Flock Association’s website

But the more interesting associations between flocking and physics—at least to me—are in the realm of nanotechnology.

For Physics Today’s September 2002 issue I wrote a news story

Her tool of choice was the atomic force microscope, which works by measuring the tiny deflections of a cantilever as it’s dragged delicately across an atomically bumpy surface.

In our knees and other joints, GAG molecules make up one component of an aqueous gel that occupies a collagen scaffold. To study their interactions, Ortiz created a carpet of tethered GAG molecules and soaked it in an aqueous solution. By attaching a GAG molecule to the tip of a cantilever, she and her colleagues could measure the GAG–GAG forces under a range of conditions.

Her conclusion: Electrostatic repulsion does indeed underlie cartilage’s ability to resist compression.

A miniature x-ray tube

p>More recently, I came across another paper that reminded me of flocking. Electron beams are typically produced in the same way as they were by J. J. Thomson in 1897 when he discovered the electron: By heating a metal cathode to “boil off” electrons, which are then pulled away and accelerated by an electric field.

But if you could make the cathode pointy enough, you wouldn’t need to heat it. Thanks to the field effect, the same electric field that accelerates the electrons can draw out the electrons from the cathode. Dispensing with heating not only saves energy, it also enables faster operation.

The tips of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are narrow enough to serve as field emitters. For the past decade, various research groups around the world have been investigating their use as field emitters in various applications, including x-ray tubes. As is the case in traditional x-ray tubes, x rays are produced through bremsstrahlung when accelerated electrons slam into a transition-metal anode.

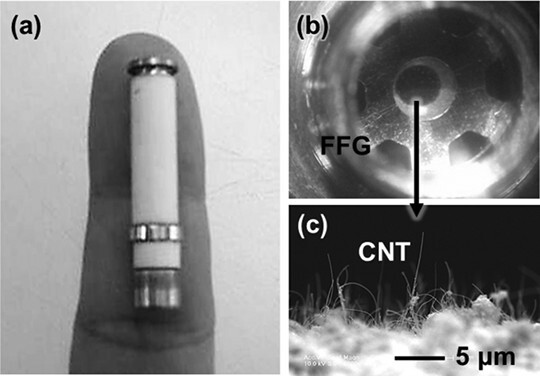

In a paper

The x-ray tube that Yoon-Ho Song and his colleagues made is small enough to fit on the tip of a finger. Panel b shows the CNT-covered cathode as viewed through the focusing functional gate (FFG). (From J.-W. Jeong et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 023504, 2013.)

As you can tell, the x-ray tube really is tiny—just 6 mm in diameter and 32 mm in length. Despite its size, the tube is fully functional. Yoon-Ho Song and his team used it to image the innards of a computer mouse. He envisions the tube could be used to deliver x-rays for brachytherapy, radiography, and spectroscopy. Because the field effect is controlled electrically, the x-rays can be turned on and off instantly; their flux can be metered precisely.

And in the scanning electron microscope image in panel c, the CNTs resemble the tufted surface of flocked wallpaper.