Hydra, fruit flies, and stripy colonies of bacteria

DOI: 10.1063/PT.5.010147

In 1952, two years before his untimely death at the age of 41, the mathematician Alan Turing wrote an influential paper

Turing’s mechanism relies on the competition between a slow-diffusing chemical—a morphogen—that activates a reaction and a fast-diffusing chemical that inhibits the reaction. Nudging the reaction-diffusion system into a metastable state yields stable stripes, spots, and other patterns.

Judging by his paper’s abstract, Turing was inspired, in part, by Hydra, a genus of simple, water-dwelling animals whose body plan consists of a single sticky foot, a stem, and 1–12 thin, neurotoxin-charged tentacles. Although his mechanism presumes a continuous, two-dimensional system, its basic premise—that pattern development is controlled by the concentration-dependent diffusion and inhibition of signaling molecules—is observed in three-dimensional, multicellular systems, notably in biologists’ favorite fly, Drosophila melanogaster.

In common with other signaling molecules, morphogens initiate a complex chain of biochemical steps. For a flavor of that complexity, here’s how the University of Tokyo’s Testuya Tabata and Yuki Takei described the action of one Drosophila morphogen, Dpp, in a primer

The pathway that transduces the Dpp signal involves a combination of two types of serine/threonine kinase receptors, type I and type II. The activated type I receptor phosphorylates cytoplasmic transducers, so-called receptor-regulated Smads (named after the first-identified members of this family: Sma in C. elegans and Mad in Drosophila), which, upon phosphorylation, translocate into the nucleus and regulate the expression of target genes (Fig. 4A). In Drosophila wing development, Thickveins (Tkv) acts as a type I receptor; its constitutively active form (Tkv*), when ectopically expressed, can induce the expression of the target genes sal and omb (Fig. 4).

Each step in the Dpp pathway provides an opportunity for regulation, thereby helping to ensure that a larval fruit fly stays on course to develop properly functioning wings. Given the high biological stakes—a fly with malformed wings can’t feed or breed—the complexity of the Dpp pathway is understandable and evolutionarily inevitable.

A paper

The genetic engineering that underlay the pattern formation involved three basic steps:

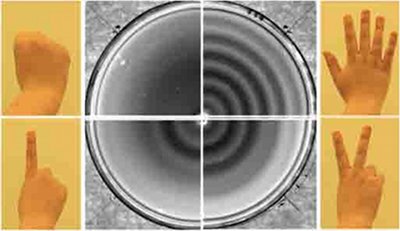

The stripes result from the bacteria’s density-dependent mobility. As a colony starts consuming nutrient and proliferating, the density of bacteria in the center rises and a front of low-density bacteria expands from the center into fresh nutrient. At the center, the proliferating bacteria cross the density threshold at which AHL, through the secretion of CI and the suppression of cheZ, deprives the bacteria of their swimming ability. Those central bacteria still eat and proliferate. As they do so, their density continues to rise until the nutrient is exhausted. The upshot is stable circular patch of high bacterial density.

The bacteria just beyond the central patch are still mobile. Some of them move inward and become trapped; others move outward, remain mobile, and create a second high-density region behind the still-expanding front. As before, when the nutrient runs out, a stable patch of high bacterial density is left behind—this time in the shape of ring. Between the two high-density regions lies a stable low-density region that marks the zone where inward- and outward- moving bacteria met different fates. The creation of ring-shaped stripes continues until the front reaches the edge of the dish and the nutrient runs out.

By formulating a mathematical model of stripe formation, the Huang–Hwa team could predict the conditions under which stripes form and whether they form at all. And by adding an extra genetic modification, one that allows the suppression of cheZ to be tuned, the researchers could test their model. It passed.

The Huang–Hwa team closes its paper by noting that the formation of stripy colonies of bacteria suggests that periodic structures can form autonomously in individual organisms without the intervention of a biological clock. To me, the stripy colonies suggest something else: That the complex pattern formation mechanisms in Drosophila and other higher organisms evolved from something akin to the genetically engineered mechanism in the bacteria.