Why go offshore?

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.0633

The Cambridge University Energy Network’s annual conference in June gave engineers and economists fresh perspectives and updates on offshore wind energy. Peter Tavner, of Durham University’s School of Engineering and Computing Sciences

Moving from land to offshore

The UK uses some 400 terawatt (TW) hours of electricity each year. Whereas there is enough fossil fuel right now to sustain that level of consumption, there won’t be forever.

Enter wind turbines. Wind traveling at 6 m/s can generate 140 W/m2 of power. But according to Betz’s law, developed in 1919 by physicist and wind turbine pioneer Albert Betz, no turbine can capture more than 59.3% of wind’s kinetic energy. The actual power output of a wind farm is described by the capacity factor, or ratio of energy generated in a year to the product of turbine rating (measure based on peak power output in high wind) and number of hours in a year. The UK’s wind resource is potentially 1000 TW hr/year, says Richard McMahon of the Electricity, Power and Energy Conversion Group

Thus engineers and politicians are looking to the North Sea’s abundant wind as one sustainable source of power generation. Martin Elliot, of consultancy BVG Associates

Wind farms are much easier to build and repair on land than offshore. And because maintenance of offshore equipment requires good weather and calm sea conditions, the equipment must have excellent reliability. But Tavner and McMahon believe that the greater potential power of offshore wind farms outweighs their greater maintenance cost.

One suggestion for effectively moving wind farms offshore has been to build a connection with a high-voltage, direct current

‘In Europe, each company [builds turbines] its own way, so you need a very specific part for each turbine,’ adds McMahon. Chinese manufacturers, however, treat them as a commodity: ‘This leads to cheaper, generic parts, but are they as reliable?’

Reducing the cost

A critical way to reduce offshore power station costs is to minimize failure and the associated downtime which limits the availability of the power station. Only when a power station is up and running can it produce electricity and meet the cost needed to maintain it.

Tavner claims that 75% of turbine faults cause 5% of downtime, and 25% of turbine faults cause 95% of downtime. And although a station’s capacity to generate electricity increases in the winter due to increased wind, availablity drops because it’s harder to maintain the turbines.

Accurate detection of problems and mobilization of people, skills, and ships will help minimize downtime. Tavner says, ‘The big problem is that renewables are distributed and harder to organize, and an entire infrastructure is needed to support what is there.’ On land, it’s easy to load tools into a van and drive to carry out maintenance. But the ships and calm seas necessary for offshore repair are harder to come by.

Wind power stations, like aircraft or nuclear power plants, need to have high reliability, with the only down time limited to scheduled maintenance. And turbine monitoring systems need to be improved so that false alarms don’t create unnecessary downtime. The basic technology for transmitting power from turbine to power grid is already in place because of past work done onshore, but transferring this technology to an offshore environment is complicated.

Egmond aan Zee: A case study

Now in its fifth year of operation, the offshore wind farm Egmond aan Zee, located 10 km off the coast of the Netherlands, experienced 140 days of downtime in 2010 due to weather. The 36 Vestas turbines in that government-supported demonstration project (operated by Shell energy and petrochemical companies) improved their availability from 83% in 2009 to 94% in 2010. About 10% of downtime was due to gearbox faults, but downtime decreased to 0% over the course of the year.

Elke Delnooz, operation support manager for Shell Wind Energy

‘You have to go offshore to make [wind energy] work; there’s just not space onshore,’ says Delnooz, confirming McMahon’s comment that since wind farms can’t be put in urban or wild areas, the sea is a sensible option.

A work permit is required to enter the 500-m zone around the Egmond aan Zee wind farm. Annual servicing is planned during the low-wind season (April), with multiple teams visiting the offshore farms to do work. Everything is systematically checked over, including the ‘monopiles’ that are hammered into the ground on top of which the turbine is attached, the rocks built around the monopiles to protect them from scouring, and the subsea transmission cables.

Repairs so far have included systematic replacement of gearboxes and generators. The monopiles experienced significant vertical settling between the foundation pile and the transition piece connected to the turbine. The bottom of the foundation piles were filled with concrete until a better plan could be developed.

Currently, Egmond an Zee uses onshore rigs that have simply been installed offshore. But future turbines such as the Vesta 164 are designed specifically for offshore farms. Although Egmond aan Zee is a 20-year investment, Delnooz ‘can’t imagine we’d actually take it down then if it’s still running.’

But at that point, both licensing and funding will have to be renewed.

Financing offshore

Somebody has to pay for offshore wind farms, says Stephanie McGregor, director of offshore transmission for Ofgem, the Office of the Gas and Electricity Markets

Ofgem’s Offshore Transmission Owner (OFTO) opportunity creates an entity licensed to provide transmission services from an offshore wind turbine to an onshore station. An appointed OFTO is granted a license with a 20-year revenue stream and must develop and maintain transmission services. A competition accessible to debt and equity providers, pension providers, and others gives developers a chance to demonstrate their financial commitment and provide data to allow capital assessment. Once an OFTO is identified, Ofgem can transfer assets and grant a license.

The OFTO is required to comply with industry best-practice to minimize the effect and duration of transmission outages, provide written statements of compliance, and repair assets. Failure to provide those services can result in its license being revoked.

‘This is a relatively low risk asset class . . . a 20-year revenue stream with limited regulatory intervention,’ explains McGregor.

For the UK to meet its offshore wind power aspirations, McGregor says that upwards of £200 billion will be required over the next decade. She also notes that capital markets are fragile and investors crave certainty and stability. Ofgem’s commercial and regulatory structure is intended to create a transparent process accessible to different funding approaches and to also provide the requisite stability needed to attract investors.

The future

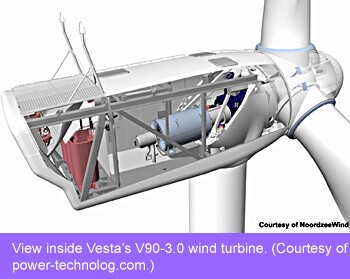

Elliott points out that until a few years ago, the offshore wind industry had only a few players. Now, although Vestas

As wind farms are built farther offshore, they face challenges associated with increasing water depths and longer transmission cables. But the benefits will be worth it. Whereas the average turbine rating is currently just under 4 MW, it will be 5–6 MW in 2015–18, Elliott says. The cost of energy should drop as drive trains and electrical systems improve and operation procedures are made more efficient.

‘Naysayers want to make [offshore wind] not succeed by comparing it to fossil fuel,’ says Tavner. But unlike fossil fuels, wind is abundant and available, and a new system is needed to support renewables such as wind and to extract energy at a high capacity. Engineers and policy makers are now asking questions about creating an infrastructure for long-term renewable energy options. The answer to many of those questions, my friend, is blowin’ in the [off-shore] wind.—Rachel Berkowitz