When continents collide

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.2466

When slabs of continental lithosphere collide, interesting things happen. Most apparent is the uplift of a mountain range—like the Himalayas, where the Indo-Australian plate has been colliding with the Eurasian plate for millions of years. But less easily observable aspects of plate interactions also lead to some fascinating geophysical investigations.

The collision process begins as thin, dense, oceanic crust—the outermost part of Earth’s lithosphere that covers ocean basins and is made of basalt and other mafic rock—is slowly consumed beneath thick, buoyant continental crust, which is made of less dense rock, such as granite. Subduction involves both the crust and uppermost solid mantle, the dynamics of which are affected by the type of crust it carries.

Normal subduction continues as long as the oceanic crust is exposed, but eventually the continental crust supported by the downwelling slab arrives at the subduction zone. Entering the oceanic trench, the slab collides with the other overriding plate and folds upward into mountains (this Geocraft link

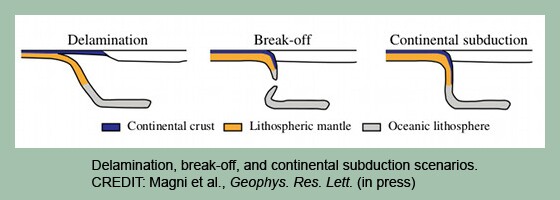

This transition from oceanic subduction to continental collision is complex and diverse, and the fate of continental and previously subducted oceanic lithosphere may lead to several different subsurface scenarios.

|

First, the continental material could continue subducting due to the pull by the previously subducted and still-attached oceanic lithosphere. Second, as Peter Bird proposed

Each pattern creates similar pre-continental collision dynamics: Oceanic subduction occurs and the downwelling slab rolls back, causing the trench to retreat. As continental collision occurs, the positive buoyancy of continental material resists subduction, so velocity decreases sharply.

But whether break-off or delamination happens next depends, among other factors, on lithosphere rheology. The widely recognized continental rheology model is the ‘jelly sandwich,’ in which a strong crust and strong mantle are separated by a weak ductile layer at the base of the crust. In a forthcoming paper

In the paper, Magni and her collaborators argue that a low lower-crust viscosity favors delamination because it eases mechanical decoupling between crust and lithospheric mantle. The slab continues to subduct, and the front where lithospheric mantle detaches from overlying crust retreats from the original suture zone. By contrast, high lower-crust viscosity—particularly when coupled with higher lithosphere viscosity—favors break-off: Thermal weakening and high tensile stress cause a break between the dense oceanic and buoyant continental material. But while the trench retreats during oceanic subduction, it migrates toward the overriding plate once continental material enters the subduction zone preceding a breakoff event.

Delamination means that, because a large portion of the dense lithospheric material is removed, the remaining material can rapidly uplift into mountain ranges. Slab break-off is associated with earthquakes and also with magmatism—thanks to upwelling from the asthenosphere, the layer just below the lithosphere. Further, a high lower-crustal viscosity is likely representative of an older continental plate, while lower viscosity may indicate a young plate more likely to undergo delamination.

Study of rheological effects and specific regions will provide more detailed models of relationships between continental collision scenario and surface observations.