What’s old is new in DOE’s choice of fusion hopefuls

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5288

Among the eight fusion startup companies that will share $46 million in grants to help build commercial power plants are four that are pursuing approaches—stellarator, magnetic mirror, and Z pinch—that were once major programs in Department of Energy labs before being mostly abandoned in favor of tokamaks.

Awardees also include two companies that are pursuing differing approaches to inertial fusion. Two others are developing tokamaks.

DOE says the grants will assist the companies to develop their respective designs for commercial fusion pilot plants in 5–10 years. At least one recipient, the MIT spin-off Commonwealth Fusion Systems, has said it will begin constructing a pilot power plant within five years. It has raised more than $2 billion. The well-established Cambridge University spin-off Tokamak Energy has been working on its spherical tokamak design for more than a decade in the UK. Officially, its award went to a US subsidiary in West Virginia.

The 18-month grants are the first tranche of an anticipated $415 million in DOE support over five years. But awardees won’t receive any of the money unless they produce acceptable “pre-conceptual designs and technology roadmaps” for their power plants within the next year and a half. According to DOE a preconceptual design is similar to a conceptual design but at lower levels of fidelity and with greater uncertainties. A technology road map details the required critical-path R&D, including any intermediate test facilities, required for a particular pilot plant conceptual design.

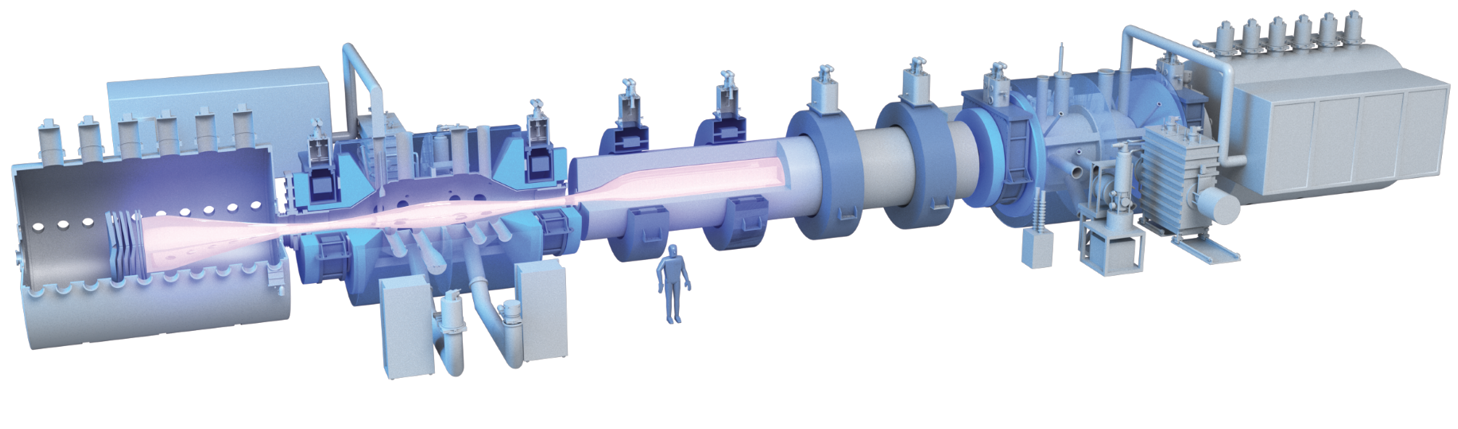

A rendering of Realta Fusion’s conceptual tandem-mirror reactor, consisting of two end cells on either side of a longer central cell in which most of the fusion will occur.

REALTA FUSION

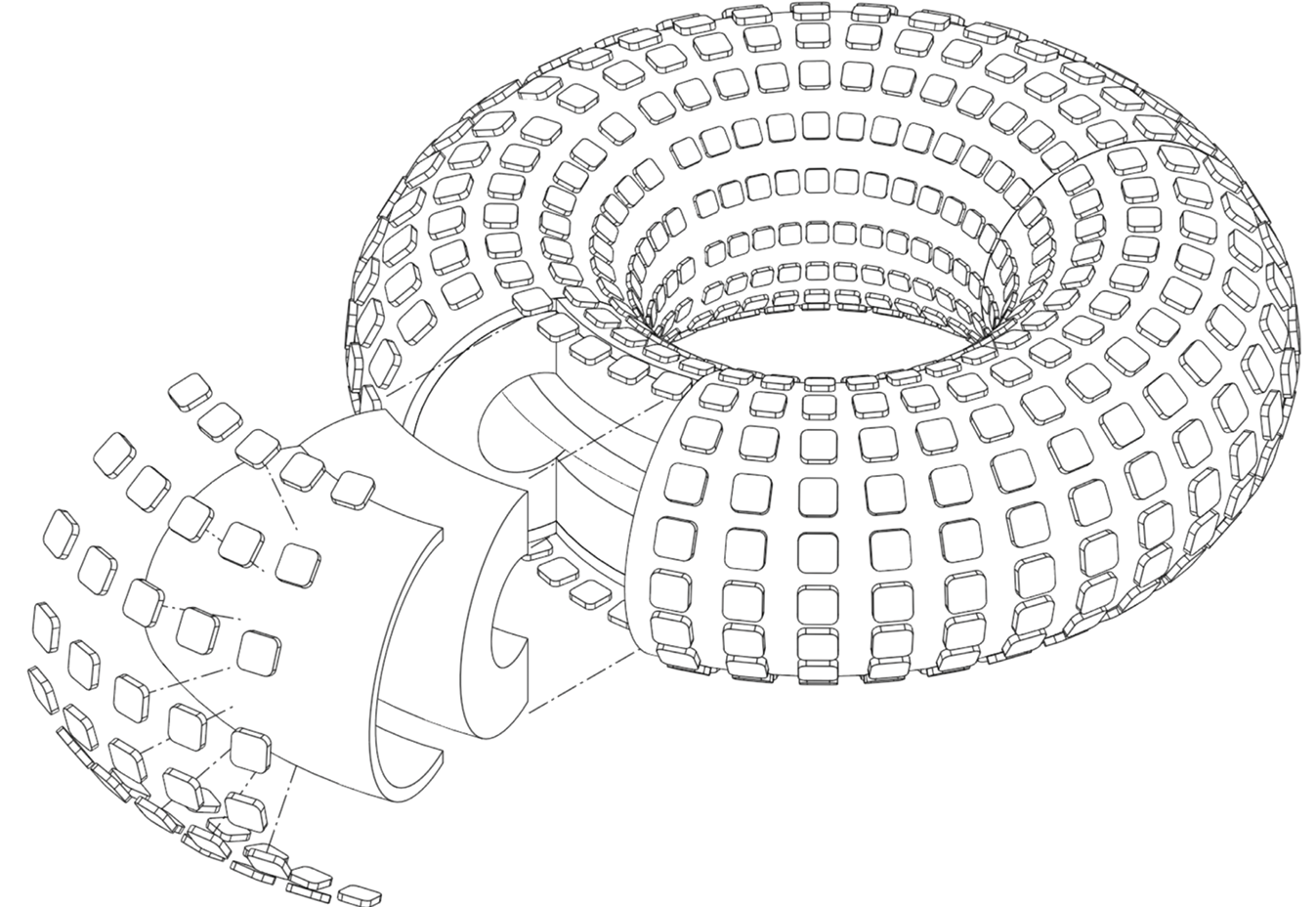

Thea Energy of New Jersey, and Type One Energy Group, based in Madison, Wisconsin, each are betting on stellarators, a magnetic-confinement concept that Lyman Spitzer pursued when he founded in the 1950s what would become the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. Like the tokamak, a stellarator creates a doughnut-shaped plasma, but it does so with a twist that requires a complex configuration of magnets to maintain.

Another Madison-based firm, Realta Fusion, is counting on magnetic mirrors, which was a major DOE program in the 1970s and early 1980s. In those cylindrical-shaped devices, charged plasma particles trapped in a magnetic field hit a point along the field line where they reverse direction. Some will collide with others and fuse as they bounce back and forth.

Zap Energy, in Everett, Washington, hopes to create commercial fusion using Z pinch, a technology that Los Alamos National Laboratory explored with its Perhapsatron machine in the 1950s. In a Z pinch, a thin line of plasma is magnetically confined and compressed by an electrical current running through the plasma. One version of Z pinch is the massive Z machine at Sandia National Laboratories, which is primarily used in support of nuclear weapons. By comparison, Zap’s reactor would fit on a tabletop.

In recent decades, DOE’s Fusion Energy Sciences program has focused nearly exclusively on tokamaks. But it has continued to support small-scale nonmainstream concepts. The Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy in particular has backed academic and privately funded research on non-tokamak approaches in recent years. In a news release, the agency boasted that the milestone awards validated its own technology choices.

Focused Energy, located in Austin, Texas, and Darmstadt, Germany, was another award recipient, as was Xcimer Energy, in Redwood City, California. They are pursuing different laser pathways to inertial fusion (see Physics Today, March 2023, page 25

Thea Energy’s stellarator design consists of arrays of small magnet coils, seen here as the outer layer of squares. Other stellarators have used thicker and more complex three-dimensional coils. The coils will be held in place by a support structure, which surrounds a thicker layer, called the blanket, encompassing the plasma.

THEA ENERGY

The awards provide an imprimatur of sorts from DOE. “The amount is less important than being part of the program,” says Benj Conway, CEO of Zap Energy, which stands to get $5 million. “Being selected as part of the program reflects our progress, the credibility of our approach, what we’ve managed to achieve, and the plan going forward.” Zap, which has raised over $200 million, has commissioned an experimental device that Conway says he expects to achieve breakeven—when fusion energy produced equals the input energy—within a year.

Assuming they meet their milestones, awardees will be eligible for follow-on grants for up to five years. The $415 million Congress has authorized for the program is subject to annual appropriations. The program’s success will depend on receiving the full out-year funding, says Conway. “That’s where it will make the real difference to us.”

Realta chief technology officer Cary Forest and Thea Energy CEO Brian Berzin say the advent of high-temperature, high-field superconducting magnets has been an important element in their respective development paths. Commonwealth Fusion Systems is supplying the high-temperature superconductor magnets for Realta’s next-generation mirror device.

More about the authors

David Kramer, dkramer@aip.org