Weighing exotic calcium isotopes

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2104

It’s long been known that certain “magic” numbers of protons or neutrons—for example, 8, 20, 28, and 50—give extra stability to nuclei. The nuclear shell model, formulated independently by Maria Goeppert Mayer and Hans Jensen in 1949, explains the magic numbers in terms of closed shells of proton and neutron orbits, much as closed shells of electron orbitals explain the stability of noble gas atoms.

But the strong interactions of nucleons are much more complex than the electromagnetic interactions of atomic electrons. So, whereas atomic shell structure is completely understood in terms of quantum electrodynamics, nuclear shell-model calculations have heretofore been able to derive the magic numbers only up to 20 in terms of fundamental interactions between nucleons. Predicting the properties of a nuclide from the shell model has, in general, been highly phenomenological. That is, it involves numerous free parameters that have to be fitted to measured binding energies and excitation spectra of nearby nuclides.

In the nuclide chart’s central “valley” of stable and long-lived species, where such measurements abound, phenomenological predictions describe well the variation of binding energy with proton number Z and neutron number N. However, on the fringes of the N,Z chart where ultrashort half-lives frustrate the requisite measurements, the predictions tend to diverge from one another.

But it’s important to know whether new magic numbers emerge in regions of extreme neutron excess—and not just for pure nuclear theory. Such extremely short-lived species are crucial intermediate stages in the supernova nucleosynthesis of elements heavier than iron (see Physics Today, August 2010, page 16

Nuclear binding energy, the roughly 1% deficit of a nuclide’s mass relative to the sum of the masses of its constituent nucleons, encodes information about shell structure. Extremely neutron-rich calcium isotopes represent an experimental and theoretical frontier. Stable 40Ca, the principal naturally occurring isotope, is doubly magic, with N = Z = 20. But known isotopes range from 35Ca to 58Ca. Beyond 52Ca, half-lives are quoted in milliseconds; so there have been no measurements of their masses. But theorists at the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany have recently been carrying out innovative shell-model calculations directly from two- and three-nucleon interactions, without free parameters, to predict binding energies from 41Ca to 54Ca.

Now a collaboration of experimenters at CERN’s ISOLDE radioactive-ion-beam facility has joined forces with the Darmstadt theory team to report 1 the first measurements of the 53Ca and 54Ca masses, compare them with the recent predictions, and extend the predictions out beyond 58Ca. The measurements confirm the emergence of a new magic number at N = 32.

Precision weighing

ISOLDE creates short-lived isotopes by bombarding a uranium carbide target with accelerated protons to induce fission reactions. The emerging fission products are roughly sorted by mass, and they can be formed into mono-energetic ion beams for prompt delivery to ISOLTRAP, the precision mass-spectrometer complex at which the new calcium weighings were carried out by a collaboration headed by Klaus Blaum (Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, Germany).

At ISOLTRAP, short-lived ions are usually weighed by measuring their cyclotron frequencies—inversely proportional to mass—in the magnetic fields of Penning traps. And indeed, the ISOLTRAP collaboration used the Penning traps to significantly improve earlier mass measurements of 51Ca and 52Ca, whose half-lives are of order 10 s. But the Penning traps couldn’t cope with 53Ca or 54Ca. More extremely neutron rich, they live only about 100 ms. And ISOLDE delivers them at much lower rates and with greater contamination from isobars (nuclei with different Z but the same Z + N) like chromium-53 and 54Cr.

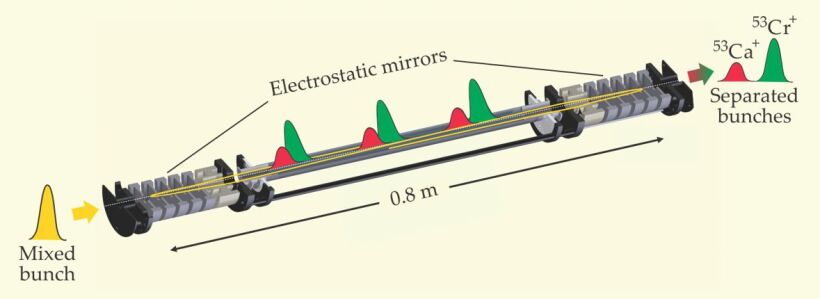

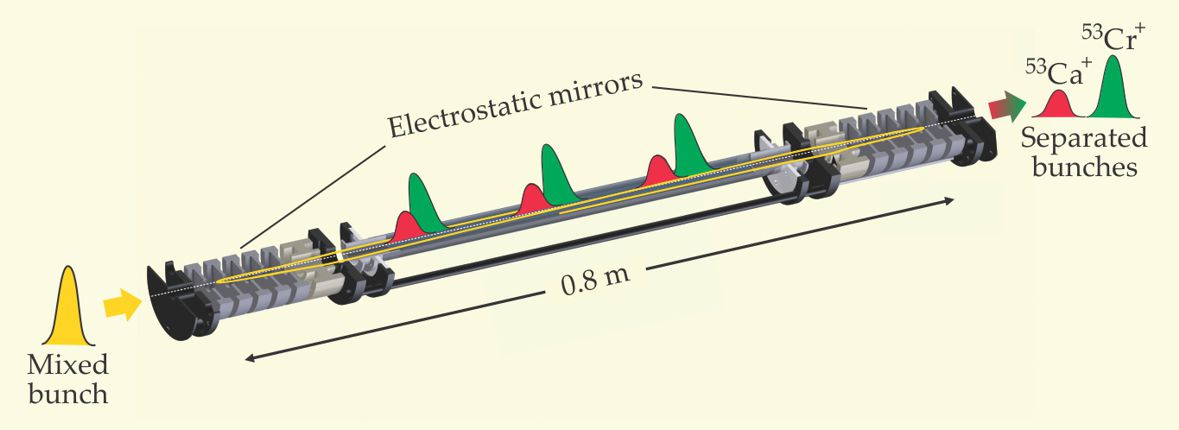

To achieve the new measurements, the collaboration replaced the Penning traps with an innovative multireflection time-of-flight mass spectrometer developed by ISOLTRAP’s contingent from the University of Greifswald on Germany’s Baltic coast. The tabletop device’s essential virtue is that repeated reflection of an incident mono-energetic ion beam by electrostatic mirrors at both ends provides kilometer-long flight paths for measuring the tiny mass differences between nuclear isobars by flight time.

In the example shown schematically in figure 1, the spectrometer receives a bunched 3-keV beam of 53Ca+ ions mixed with 53Cr+ ions of the same kinetic energy. Far from being a contaminant, the beam’s dominant 53Cr+ population serves here as the crucial calibrating reference. The mass of this stable chromium isotope is known with great precision. It’s about 0.06% lighter than its calcium isobar. So the 53Cr+ ions pull slowly but steadily ahead in repeated laps through the 0.8-m-long spectrometer.

Figure 1. The new multireflection time-of-flight mass spectrometer at CERN’s radioactive-ion-beam facility measures mass differences between nuclear isobars such as calcium-53 and chromium-53. Here a bunched beam containing 3-keV 53Ca+ and 53Cr+ ions bounces repeatedly between electrostatic end mirrors. As the flight path lengthens, the slightly lighter 53Cr+ ions forge ahead. Ejected after several hundred round trips, the two species have formed well-separated bunches whose flight-time difference yields a precision measurement of their mass difference. (Adapted from ref.

Extracted after a few hundred laps—roughly a millisecond—an initially mixed bunch has become two well-separated bunches, with the Cr bunch reaching the exit timer first by about a microsecond. From the time profiles of many such bunches, the collaboration derived an isobaric mass difference precise enough to yield a 53Ca binding energy of 441 524 ± 43 keV. For 54Ca, the spectrometer yielded a comparably precise result, in that case with stable 54Cr as the reference isobar.

Binding trends

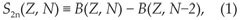

Nucleons, like electrons, are spin-1⁄2 fermions. So neutron orbitals also come in coupled opposite-spin pairs. Therefore, a useful descriptor of binding trends at high neutron excess is the two-neutron separation energy

where binding energy B is, by convention, positive.

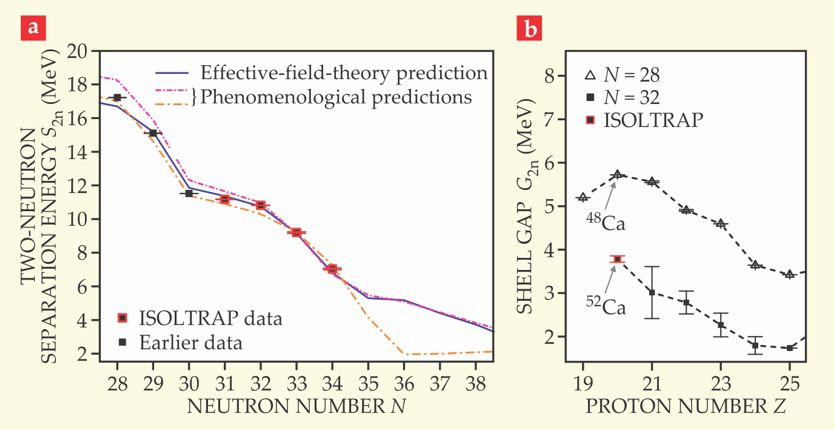

Figure 2a shows the measured falloff of S2n for calcium isotopes from the almost stable, doubly magic 48Ca through the new ISOLTRAP measurements. The steep drop after N = 32 (52Ca) looks much like the drop after the known magic number N = 28 (48Ca).

Figure 2. Binding-energy trends. (a) The measured two-neutron separation energies S2n (defined in terms of binding energies by equation 1) of neutron-rich calcium isotopes are plotted against neutron number N. The data are compared with predictions from an effective field theory based on quantum chromodynamics

“Unambiguously, we’re seeing N = 32 emerge as a new magic number in this region of extreme neutron excess,” says Jason Holt, one of the Darmstadt theorists. The new magic neutron number had earlier been hinted at by gamma-spectroscopy measurements of excited states of the 52Ca nucleus.

The strength of the neutron-shell closure at N = 32 can be evaluated from the variation of the two-neutron shell gap G2n, which compares a nuclide’s binding energy with the mean of two flanking isotopes:

Figure 2b plots the measured shell gaps at N = 28 and N = 32 for calcium and nearby elements. The falloff with increasing Z after 52Ca is as steep as the falloff after 48Ca, whose doubly magic character has long been established.

“Finding a pronounced structural effect at so great a neutron excess challenges the prejudice that such effects must smear out near the limits of nuclear binding,” says ISOLTRAP collaboration member Vladimir Manea (Université Paris–Sud).

Predictions

In figure 2a, the S2n data are compared with two representative phenomenological predictions based on older measurements of binding energy up to 50Ca and nuclear excitations up to 52Ca. Those predictions agree reasonably well with the ISOLTRAP binding energies. But they diverge badly beyond 54Ca. Furthermore, the phenomenological predictions of nuclear excitations (not shown) disagree with each other beyond 52Ca.

Figure 2a also shows the Darmstadt theory team’s latest predictions, out to 58Ca. Since 2010, Holt and Achim Schwenk, leader of the Darmstadt team, have been spearheading attempts to produce reliable shell-model predictions for neutron-rich nuclides by considering only two- and three-nucleon interactions derived from low-energy approximations to fundamental particle theory. The results reproduce well all the measured Ca binding energies and excitation energies. Yet they involve no empirical nuclear inputs except for the binding energy of the triton (3H) and the charge radius of the alpha particle (4He).

The team’s approach seeks to describe the interactions of individual valence neutrons—beyond the last closed shell—in terms of an effective field theory (EFT) that approximates quantum chromodynamics, the fundamental theory of the quarks and gluons, at the low energies appropriate to nuclear physics. Thus the EFT ignores quark degrees of freedom and describes nucleon interactions by the exchanges of virtual pions rather than gluons.

Beyond two-nucleon interactions due to pion exchange, the theory team includes three-nucleon interactions that involve, for example, the simultaneous exchange of pions between one neutron and two others. It’s the three-nucleon interactions that, in the EFT approximation, require the empirical triton and alpha-particle inputs.

”The inclusion of three-nucleon interactions turns out to be essential for correctly predicting the newly measured masses,” says Schwenk. Without them, one can’t even reproduce the 48Ca mass. “As experimenters impressively advance our understanding of extreme nuclei,” he says, “we look forward to comparing our predictions beyond 54Ca with measurements still to come.”

References

1. F. Wienholtz et al., Nature 498, 346 (2013).https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12226