Understanding how metal-nitride ferroelectrics switch their polarization

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.5286

Studied for more than a century, ferroelectric materials exhibit a spontaneous polarization in one or more directions along a crystal axis. Thermodynamically stable, the polarized states can be switched from one to the other by applying an electric field that exceeds what’s known as the coercive field Ec. That switchability provides the basis for the nonvolatile RAMs in computing. (See the article by Orlando Auciello, James F. Scott, and Ramamoorthy Ramesh, Physics Today, July 1998, page 22

Since the 1960s, electrical engineers have been designing memory elements based on conventional ferroelectrics such as the perovskite barium titanate. But manufacture is complicated by the challenge of integrating those materials with silicon-based semiconductors. What’s more, the memory elements are difficult to scale down to atomic dimensions for energy efficiency. Between 2019 and 2021, researchers discovered that crystalline films of alloyed aluminum nitride are ferroelectrics that could solve both problems. Boron-doped AlN, in particular, is easy to integrate, as it consists exclusively of elements common in silicon electronics.

The discovery was a surprise to most scientists. The films were well-known pyroelectric and piezoelectric crystals, but few believed they could be ferroelectric, because their coercive fields are just too perilously close to the field at which the materials experience dielectric breakdown. Apply a high enough electric field to switch the polarization and you risk destroying the material.

Pennsylvania State University materials scientists Jon-Paul Maria, Susan Trolier-McKinstry, and Ismaila Dabo, who had demonstrated ferroelectricity in B-doped AlN two years ago, 1 have now teamed up with Carnegie Mellon University materials scientists Sebastian Calderon and Elizabeth Dickey to address the dielectric-breakdown problem. 2 The collaborators realized that if they understood the mechanism by which the polarization switches at the atomic scale, they could manipulate it—for example, by straining the film, growing it thinner, or altering its dopant concentration.

Such tricks may dramatically lower the coercive field from roughly 4–6 MV/cm in metal nitrides down to levels approaching 1 MV/cm. That transformation would render the new ferroelectrics more practical for applications in memory, energy-harvesting, and high-speed and high-power circuits.

Double duty

Fortunately, there are a few ways to ensure that the coercive field is lower than the dielectric breakdown field. At elevated temperatures, the margin separating Ec and the breakdown field increases, for instance.

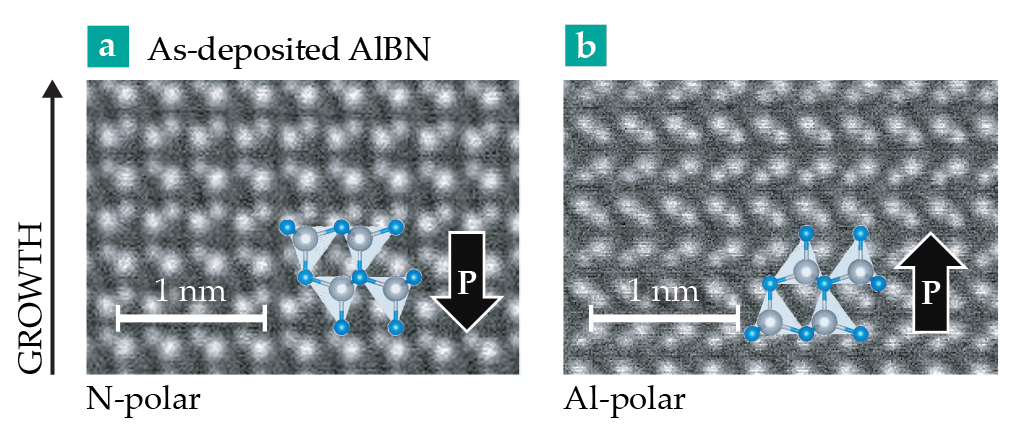

As deposited on a tungsten electrode, Al15/16B1/16N films grow with a polarization that points downward (into the substrate)—a configuration shown in figure

Figure 1.

Before and after polarization reversal. These transmission electron microscopy images are on-edge views of a boron-doped aluminum nitride film—a mere 6 nm thick—that show the projections of N, Al, and B atoms through the lattice. (a) In AlBN as it’s deposited on tungsten, the polarization orientation P is down, or N-polar. (b) After the surface expels enough charge to exceed the coercive field, the polarization flips upward (Al-polar) and the angles between the N atoms and the Al or B atoms change their relative orientation. (Adapted from ref.

To experimentally study the films’ local structure and polarization, the researchers used scanning transmission electron microscopy (TEM). And in a standard imaging mode known as differential phase contrast, the microscope images the sublattices of the heavier (Al) and lighter (N) atoms at the same time. The atomic columns appear as distinct projections through the lattice.

The TEM beam also can trigger a polarization switch: As electrons scatter in the film, they ionize local Al, B, and N atoms. Electrons are ejected, and the sample becomes positively charged. When a local electric field exceeds Ec, the film’s polarization switches upward (figure

Imaging the configuration of atoms during the switching process takes about seven minutes. But that time is largely spent charging the sample to the coercive field. And the TEM affords researchers the luxury of imaging continually while the charging takes place. In practice, actual ferroelectric devices flip their polarization far faster—on time scales of about a nanosecond.

Inversion through a flattened plane

When they joined the project, Maria and Dickey initially imagined that each metal atom in a tetrahedron would break one of its N bonds. The Al or B atom would then move into the plane of the three remaining N atoms before protruding to the other side, where it would then bond with another N atom. That would be the simplest, most intuitive way to switch the polarization.

But for it to work, they realized, B atoms would be needed to flatten the tetrahedra. Like graphite, BN crystallizes in a planar hexagonal lattice, and B is energetically more likely to adopt a three-fold coordination in covalently bonded sheets than to adopt a four-fold one.

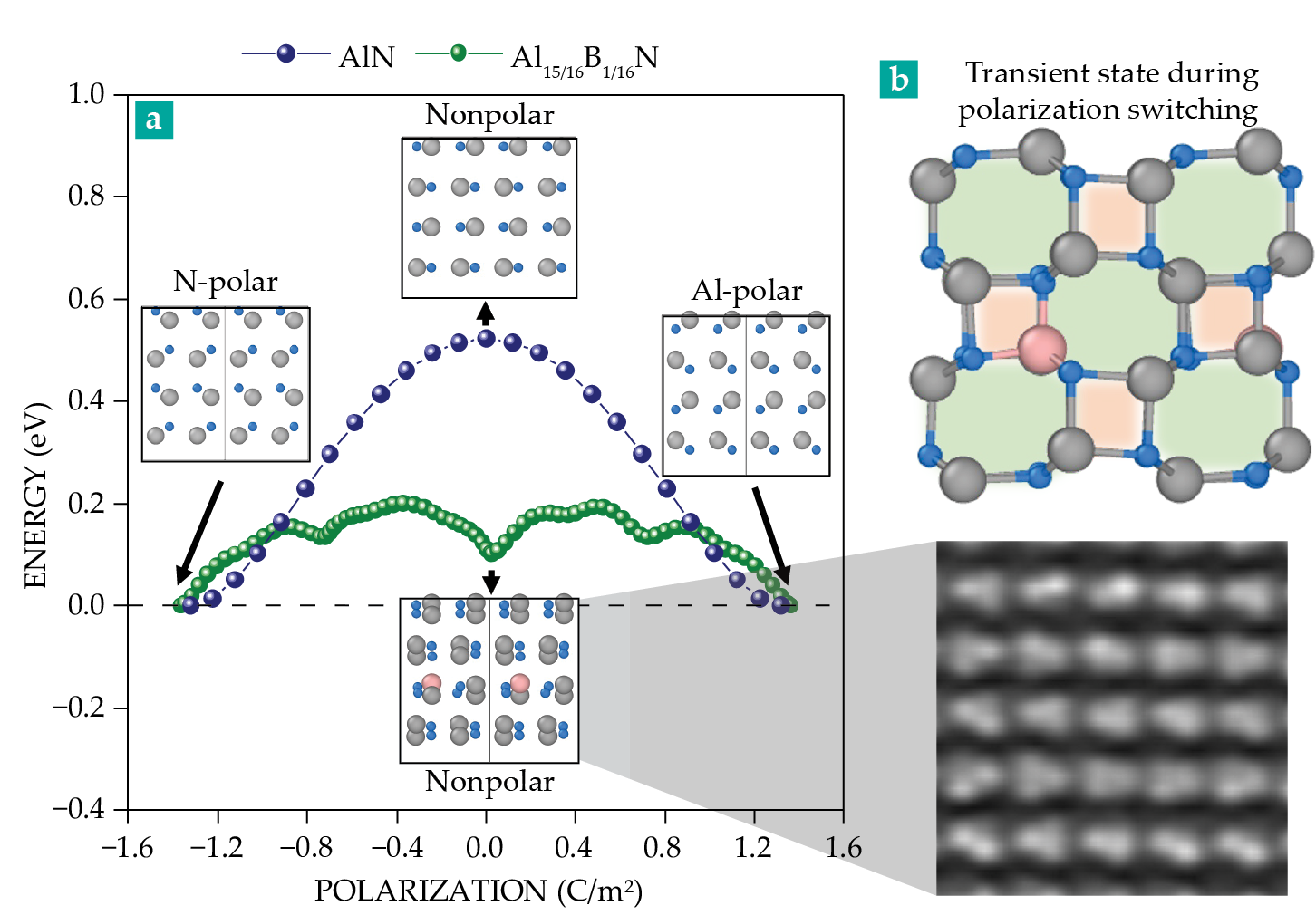

By passing through an intermediate stage in which the AlN tetrahedra flatten, the Al–N dipoles were expected to cancel and the polarization to drop to zero. In the collaboration’s new work, first-principles calculations by graduate student Steven Baksa from the Dabo group bore out that imagined scenario (the blue curve in figure

Figure 2.

A first-principles calculation. Researchers move aluminum and nitrogen atoms in a film of aluminum nitride to determine the minimum energy pathway required to switch its polarization from N-polar to Al-polar. (a) Along one proposed path (blue), Al (gray) and N (light blue) atoms in each tetrahedron of a pure AlN film adopt a nonpolar, linear configuration midway. But that configuration, which has a 0.5 eV energy barrier, is never observed by transmission electron microscopy. Along an alternative path (green), the atoms switch polarization in multiple stages. (b) The green path’s intermediate structure was confirmed (bottom) in an experiment and predicted (top) in a nearly 30-year-old simulation to include area defects in the form of four- and eight-membered rings.

When the researchers introduced a single B atom into the calculation, a more complicated atomic structure emerged instead—one that includes substantial local bonding and structural distortions. Both N-polar and Al-polar bonding configurations appear in the transient atomic structure, combining both upward and downward polarizations in a doubled unit cell. The B-doped AlN calculation revealed that the lowest energy path to switch the polarization is not the smooth parabolic one, but rather one with local minima (green curve in figure

Reassuringly, the collaboration’s TEM image of the B-doped film (figure

The formation energy of those intermediate states—just 0.2 eV—is small enough that making them is achievable with an electric field that doesn’t destroy the material. Is there an even better switching pathway that would lower the coercive field while retaining the temperature-stable polarization? The researchers don’t yet know, but Trolier-McKinstry expresses hopeful enthusiasm: “We’re really looking forward to finding out. For starters, we will be exploring compositional modifications that could result in lower local energies for the reversal process.”

References

1. J. Hayden et al., Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 04412 (2021).

2. S. Calderon V et al., Science 380, 1034 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh7670

3. J. E. Northrup, J. Neugebauer, L. T. Romano, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 103 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.103