Ultracold Gases of Fermionic Atoms Offer Another Path to Atom Interferometry

DOI: 10.1063/1.1801857

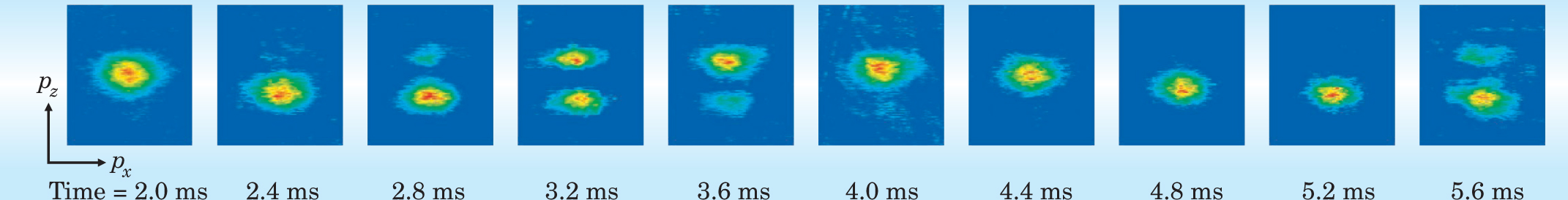

Early this year, when researchers at the University of Florence in Italy saw the oscillating pattern shown in the figure below, with a peak in intensity appearing first at one value of momentum and then at another, they knew that ultracold fermionic atoms were viable candidates for atom interferometry. 1

Fermions are somewhat surprising candidates for this application. Most attention to date has focused on Bose–Einstein condensates (BECs), which look especially promising for precision atom interferometry because all the atoms are in the same ground state and the macroscopic wavefunction can interfere with itself. As David Pritchard (MIT) puts it, BECs are to matter-wave interferometry what lasers are to optical interferometry: a coherent, single-mode, and brilliant source.

In the case of fermions, however, the Pauli principle prevents two atoms from simultaneously sharing the same state; thus there is no macroscopic coherence. What the Florence group, led by Massimo Inguscio, has now shown is that one can still get interference effects from fermions. The interference stems from single particle wavefunctions.

It has long been known that the waves associated with single electrons and neutrons can interfere with each other. In 1991, several groups demonstrated matter-wave interference in atoms as well (see Physics Today, July 1991, page 17

Researchers have used atom interferometry as a tool for sensing acceleration and rotation, for monitoring quantum decoherence, and for precision measurements of such quantities as the acceleration of gravity or the ratio of Planck’s constant to the mass of an atom. A key advantage of quantum degenerate fermions for atom interferometry is that they do not have the kind of collisions that can quickly destroy or shift an interference pattern. Pierre Meystre (University of Arizona) points out that they also offer the atomic equivalent of white-light interferometry. The downside is the difficulty in cooling the fermions.

In 1998 at Yale University, Brian Anderson and Mark Kasevich (now at the University of Arizona and Stanford University, respectively) demonstrated the macroscopic quantum interference one can get in a BEC by putting a gas of rubidium-87 atoms in a one-dimensional, vertical optical lattice. 2 The optical lattice—a standing wave created by counterpropagating laser beams—essentially provided “shelves” of different heights on which one could stack slices of the condensate. When the lattice was removed, the atoms tunneled down out of the BEC from different shelves and produced the predicted interference.

At Florence, Inguscio, Giovanni Modugno, and their colleagues tried a similar experiment, but with ultracold fermions in a magnetic trap. They cooled potassium-40 atoms to 100 nK, well below the Fermi temperature at which the fermions fill in all the lowest energy levels. Once they had cooled the atoms and placed them in a vertical lattice, the experimenters turned off the magnetic field and let the atoms evolve for different lengths of time in the combined gravitational and optical potentials. To detect the momenta of the atoms, the Florence team turned off the optical lattice and let the cloud expand freely. By imaging the positions of atoms in the expanded cloud, the group essentially determined their momentum distribution.

Unfortunately, each such measurement destroys the atom cloud, so that every photo in the figure below was taken with a different atomic cloud. Nevertheless, the sequence does still represent the time evolution of a single cloud.

The images in the figure show the vertical momentum as a function of the time the atoms are held in the optical and gravitational trap. Notice that the peak in the momentum distribution of the atomic cloud moves smoothly toward a lowest value and then starts again. This pattern is known as a Bloch oscillation, and the Florence group was able to observe the oscillations over a remarkable 110 cycles.

To understand why the system should oscillate between two values of momenta, consider the initial state in which atoms occupy each of many cells in the optical lattice, all the while subject to the uniform gravitational field. The situation is much like that of electrons in the periodic potential of a crystal to which one has applied a constant electrical field.

The energy spectrum of the combined optical and gravitational potential is known as a Wannier–Stark ladder of states. A constant energy difference of mgλ/2 separates successive rungs of the ladder (λ is the wavelength of the optical lattice). Each of the corresponding sets of Wannier–Stark wavefunctions is centered over one of the lattice sites but typically extends over about 10 lattice sites. The individual atoms are superpositions of such wavefunctions.

Each Wannier–Stark state has a different energy from its neighbors and consequently evolves at a different rate. The phase difference Δϕ = ΔEt/ℏ is a function of time, so that the interference pattern is also a function of time.

In analogy with the case of atoms in a crystal, one can define a Bragg momentum q B as proportional to the inverse of the spatial period of the lattice: q B = h/λ. The momentum distribution of a single Wannier–Stark state completely fills the Brillouin zone between −q B and q B in momentum space. Interference between several states, however, gives narrow momentum peaks separated by 2q B. Only one or two of these peaks appears at the same time in the first Brillouin zone. The momentum distribution thus oscillates between q B and q B.

A semiclassical way to think about this interference pattern is to picture the entire atom cloud as a single wavepacket moving uniformly in momentum space under the influence of gravity. Each time it reaches the band edge (where its momentum is –q B), it is reflected—that is, its momentum changes sign—and the cycle starts over.

Inguscio, Modugno, and their collaborators repeated their experiment, this time with bosons. They found constructive interference and Bloch oscillations. Those oscillations were much shorter lived, however, because bosons, unlike fermions, have interactions that destroy the coherence. Kasevich comments that such a comparison is hardly fair to bosons because one can optimize the conditions for bosons in various ways to get the advantage of their long coherence lengths.

Inguscio and his coworkers used the experiment with fermions to get an estimate of the acceleration of gravity, g. The period of oscillation should equal the expected Bloch oscillation period of T B = 2h/mgλ. By measuring this period, the Florence group determined g to one part in 104, compared to precision of one in 1012 sought by those interested in extremely precise gravimeters. Inguscio points out, however, that a fermion interferometer offers high spatial resolution, on the order of micrometers. With an improvement in precision of only one or two orders of magnitude, such an instrument could be used to investigate forces at short distances, such as the Casimir force.

Atoms oscillate between two values of momentum in this time sequence of photos. Each photo shows the density of an ultracold cloud of fermionic atoms as a function of horizontal (p x ) and vertical (p z ) momentum. The times indicate how long the atomic cloud was held in a combined optical and gravitational potential. In a semiclassical picture, the momentum of the atomic cloud moves uniformly from one value to another in momentum space and periodically reflects back to the first value.

(Figure adapted from ref. 1.)

References

1. G. Roati, E. de Mirandes, F. Ferlaino, H. Ott, G. Modugno, M. Inguscio, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 230402 (2004).

2. B. P. Anderson, M. A. Kasevich, Science 282, 1686 (1998).