Trump trails predecessors in appointing science agency administrators

France Córdova was sworn in as NSF director in 2014. She was kept on to lead the agency by President Trump.

Sandy Schaeffer

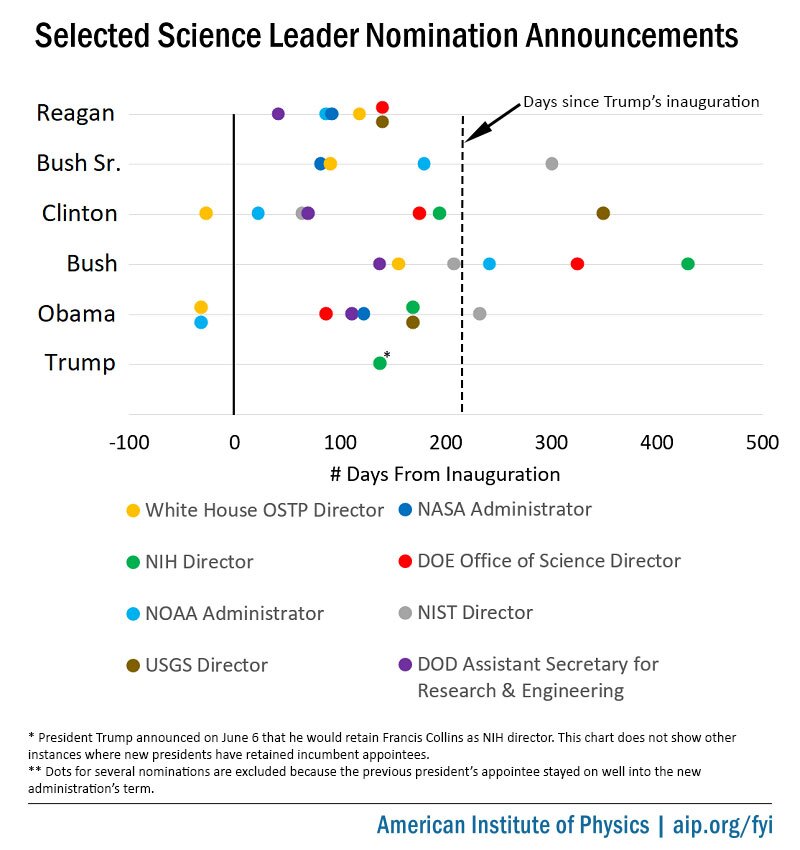

President Donald Trump has made appointments to leadership positions in federal agencies, including the science agencies, at a slower pace than his recent predecessors, which leaves most agencies with career employees in charge. Although those acting officials have the experience to perform their agencies’ essential administrative duties, they generally do not undertake major changes in policy.

Since Congress established the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy in 1976, new presidents have tended to move quickly to appoint a director, who also doubles as the president’s science adviser. Until now, the latest a new president announced his selection for OSTP director was President George W. Bush’s announcement of John Marburger on 25 June 2001. Trump interviewed two candidates in the early days of his administration but has so far made no selection.

The White House has also usually sought the advice of a body of independent experts in science and technology. President Ronald Reagan’s science adviser, Jay Keyworth, named a White House Science Council that reported to him in February 1982. In January 1990, President George H. W. Bush established the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), which reports directly to the president. President Bill Clinton did not announce his PCAST’s new membership until August 1994.

After Clinton, establishing a PCAST became a more routine part of a new administration’s work. George W. Bush named Floyd Kvamme as PCAST cochair in March 2001, three months before naming Marburger as science adviser. Bush waited until that December, though, to announce the full PCAST membership. President Barack Obama announced PCAST cochairs Harold Varmus and Eric Lander in December 2008, alongside his science adviser John Holdren. The full membership followed in April 2009. There has been no word on when, or even whether, Trump intends to establish a PCAST for his administration.

New presidents have generally made most of their key science agency appointments by their 200th day in office.

One of the few decisions the Trump administration has made in science leadership is to retain Francis Collins, an Obama appointee, as director of the National Institutes of Health.

Although it is now unusual for NIH directors to serve multiple presidents, until the 1980s it was common. Donald Fredrickson, originally appointed by President Gerald Ford, stayed through the Carter and Reagan transitions before resigning six months into Reagan’s first term. He later recalled he remained long enough to demonstrate NIH’s independence. The next two directors, James Wyngaarden and Bernadine Healy, were both surprised to learn that the George H. W. Bush and Clinton administrations expected to make their own appointments.

The next two directors, Varmus and Elias Zerhouni, stepped down before the end of the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, respectively, leaving the position open for the next president to fill. Bush did not appoint Zerhouni until March 2002.

Unlike the NIH director, the National Science Foundation director, who serves a six-year term, has remained essentially unaffected by turnover at the White House. In recent decades, only Walter Massey, who took a senior position at the University of California system in 1993, has stepped down at the beginning of a new administration. Trump has followed the general tradition, leaving in place France Córdova, whom Obama nominated in 2013.

As with the NIH director, some president-appointed positions at science agencies only began to turn over with new presidential administrations in recent decades. Those include the directors of the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the US Geological Survey. Other positions, such as the administrators of NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the heads of R&D at the Energy and Defense Departments, have always been subject to turnover with a new administration.

New presidents have occasionally chosen to leave in place appointments made by presidents of the opposing party. Clinton retained Daniel Goldin as NASA administrator, George W. Bush retained Charles Groat as USGS director, and now Trump has retained Collins as NIH director. Sometimes, though, incumbents’ hopes to stay on have been dashed. William Happer was dismissed as director of the Office of Energy Research after clashing with Vice President Al Gore over the issue of ozone depletion. USGS director Mark Myers hoped to stay on under Obama, but Obama chose to appoint his own director, Marcia McNutt, instead.

Non-scientist leadership

Separate from the question of the pace of Trump’s appointments is the issue of whether he is appointing individuals with sufficient scientific expertise. In particular, Trump appears to be reversing a trend in recent decades that raised the place of scientists within the Department of Energy.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 created a new position of under secretary for science, which has always been held by scientists until Trump’s appointment of Paul Dabbar this year. Dabbar, who is awaiting Senate confirmation, has an undergraduate degree in marine engineering but has spent most of his career in energy-sector finance.

Throughout the history of DOE, the energy secretary has traditionally come from a political rather than scientific background. In 2004 George W. Bush broke somewhat with that tradition in appointing Samuel Bodman, who has a PhD in chemical engineering but worked in finance and served as deputy secretary at the Treasury and Commerce Departments before moving to DOE. In 2009 Obama appointed Stanford University physicist Steven Chu energy secretary, and then appointed MIT nuclear physicist Ernest Moniz to the position in 2013. Trump’s selection of former Texas governor Rick Perry has returned the position to its political roots.

Trump’s selection of Sam Clovis as under secretary of agriculture for research, education, and economics—otherwise known as the Department of Agriculture’s chief scientist—has drawn severe criticism in large part because Clovis does not have a scientific background. Clovis has also come under fire for his rejection of the scientific consensus on climate change and for homophobic remarks he made as a talk radio show host. He has not yet had his Senate confirmation hearing.

Trump may make more science leadership selections in the coming months. Most notably, reports recently emerged that Trump has selected Representative Jim Bridenstine (R-OK) to serve as NASA administrator and that an announcement will come in September. Rumors have also circulated about other positions, such as that AccuWeather CEO Barry Myers will be selected as NOAA administrator.

This article is adapted from a 23 August