The triumphs and failures of astrometeorology

Medieval societies wanted more accurate weather forecasts than those offered by the classical meteorology passed down from ancient Greek and Roman scholars. Astrometeorology, which was accepted in Europe from about 1100 to 1700 CE, appeared to satisfy that demand. Texts and discoveries spread rapidly and widely across European and Middle Eastern political and cultural borders (see the article by Anne Lawrence-Mathers, Physics Today, April 2021, page 38

Classical meteorologists had noted the fundamental importance of phenomena such as winds and clouds and of their irregularity and variability. Early Christian philosophers had adopted Neoplatonic models for discussing meteorology and consequently described atmospheric phenomena in terms of theories of numerical patterns and proportions in nature. But none of those efforts provided satisfying models for analyzing weather events.

Astrometeorology popularized the belief that atmospheric phenomena and patterns of weather could be best understood and predicted through the collection and interpretation of observed data. But sadly, the underpinning theoretical basis was mistaken—namely, the belief that atmospheric changes were determined by planetary movements and the rays they supposedly emitted. Still, the fact that the model accounted for the complexity of actual weather underlies its extraordinary level of success.

Scientific and unscientific ideas

A notable characteristic of astrometeorological texts, as compared with those derived from classical literary sources, is the absence of personifications and anthropomorphic elements, such as winged men blowing air from their mouths. The system worked entirely in terms of observable, predictable planetary positions and movements whose “effects” on the atmosphere depended on accepted qualities of matter. Saturn, for example, was characterized as distant, slow-moving, and cold in color and was associated with cold, dry weather conditions.

Astrometeorology was entirely in harmony with monotheistic religious beliefs and with the idea of a mechanical universe whose patterns and laws could be observed, analyzed, and understood. Those characteristics closely linked astrometeorology to the broader developments in astronomy taking place at the same time. But the ability of astrometeorology to arguably deliver practical weather forecasts made it of more immediate interest to patrons and investors.

The complexity of the mathematical calculations required for astrometeorological forecasts, similar to those for astronomy, unintentionally contributed to the adoption of Hindu–Arabic numerals by European scholars. Shown in the picture below, the numerals make such calculations easier.

This page from Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci (The Book of Calculations) uses red Arabic numerals in the running text and in the list at the top right. The 1202 book introduced several Arabic mathematical conventions to Europeans.

Otfried Lieberknecht

A mixture of positive and negative factors can be seen in other aspects of astrometeorological theory and practice. For example, several astrometeorologists asserted that the Moon influenced all water, both in large quantities such as oceans and in small ones such as bodily fluids. Although they were wrong that the Moon affected bodily fluids and other small reservoirs of water, the detailed work done on ocean tides and their relationship to the position and phase of the Moon led to a considerable increase in accurate knowledge.

Bede, an eighth-century Anglo-Saxon monk, made important early contributions to the scientific understanding of tides. He read widely in the classical sources available to him but rejected their assertions that the tides rose and fell simultaneously everywhere. He was equally unconvinced by arguments that the supposed uniformity happened because of the movement of the Moon or the effects of subterranean watercourses and waterspouts, or because the sea was a creature that “breathed.”

Instead, Bede pointed out that as observed from a specific location, the Moon rises and sets each day 48 minutes later than on the previous day. In his book The Reckoning of Time, he linked that finding to his observation that the tides change each day “by almost exactly the same interval.” Moreover, by gathering information from people living at different places along the nearby coast, Bede established that, although the tides all followed the same rhythms, they rose and fell earlier north of his location and later to the south. Despite his careful observations, he falsely concluded that the variation was caused by a specific “bond” linking each place to the Moon.

Later, in the ninth century, the astrometeorologist al-Kindi—who probably lived and worked mostly in Baghdad—produced a wholly astrological theory of the relationship between the Moon and the tides that distinguished water flowing in rivers from ocean tides. For him, heat produced by planetary movement was responsible for the tides and atmospheric changes. He believed that the heating of the water, caused by the movement of the Moon and its closeness to Earth, expanded the water and caused tides to rise.

A related theory was expounded by the ninth-century scholar Abu MaʾShār, and both he and al-Kindi significantly influenced European astrometeorologists. Only in the 17th century did researchers begin to accurately understand that tides were caused by the Moon’s gravitational force on Earth’s oceans. Wholesale acceptance took time: Galileo Galilei, for example, rejected the gravitational explanation and thought incorrectly that the tides were caused by Earth’s rotation on its axis and revolution around the Sun.

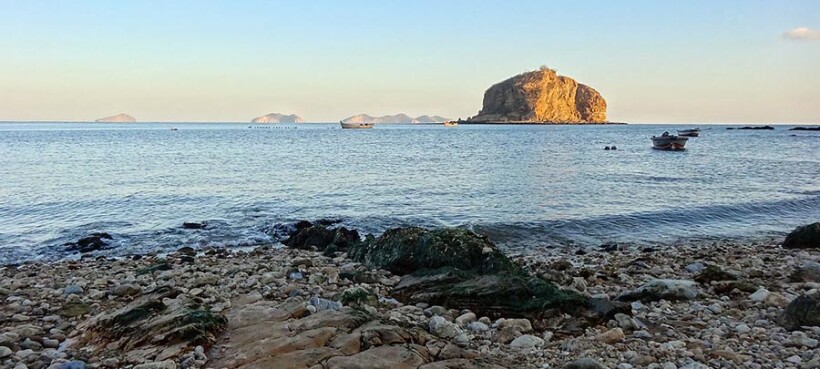

Low tide at Bangchuidao Island in Dalian, China.

JessieW900, CC BY-SA 4.0

Weather and human health

The same mixture of careful analysis and flawed assumptions can be seen in astrometeorology’s relationship to human health. The famous ancient Greek physician Hippocrates and his Greco-Roman successor Galen linked illness to variations in air quality, vapors, and bodily humors. Although physicians of the time thought that the supposed connections accounted for individual and local patterns in illness and health, they made no attempt to explain the atmospheric variations themselves.

Astrometeorology, however, did provide an explanation, albeit false, for the variations in air quality and for its effects. Various medical treatises were written after the devastating outbreaks of bubonic plague that arrived in Europe beginning in 1348. The medical faculty of the University of Paris concluded that the epidemic had been caused by a corruption of the air’s substance, which had itself been brought about by a destructive planetary configuration. Scholars also considered that the air could have been corrupted by local factors, such as decaying organic matter or prevailing winds, but the astrological cause appeared to offer a clearer explanation for the pandemic. Only in the 19th century did scientists isolate the bacterium responsible for the plague.

Astrometeorology’s correct and incorrect elements are difficult for historians to entirely separate. Despite some of the flawed theoretical assumptions of astrometeorology, it did contribute to scientific developments. And, on balance, those contributions were positive.