The theory of black hole formation shares the Nobel Prize in Physics

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4628

In a 1969 paper, Roger Penrose wrote, “I only wish to make a plea for black holes to be taken seriously and their consequences to be explored in full detail. For who is to say, without careful study, that they cannot play some important part in the shaping of observed phenomena?” 1 His success at getting researchers to consider black holes in earnest was acknowledged with half of this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics.

Roger Penrose

FESTIVAL DELLA SCIENZA/CC BY-SA 2.0

With decades of evidence, it may be hard to imagine that physicists ever doubted their existence. That evidence includes work by Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez, who received the other half of this year’s prize (see the story on page 17

In a three-page paper with few equations, Penrose showed in 1965 that black holes were not a mathematical oddity but a real-life inevitability, 2 and he introduced the mathematical framework of topology to general relativity for the first time. He is “unmatched by anyone since Einstein in his contribution to our understanding of gravity,” says astrophysicist Martin Rees.

The general idea

As early as the late 1700s, John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace had hypothesized about an object with an escape velocity faster than the speed of light, such that even particles of light couldn’t leave its gravitational field. Using Newtonian mechanics, Michell and Laplace each found that a spherical mass

That same radius would appear again more than 100 years later. In 1915 Albert Einstein published his theory of general relativity, which relied on unfamiliar and difficult mathematics that he could solve only approximately. Early in 1916, while serving in the German army in World War I, Karl Schwarzschild produced the first solution to Einstein’s field equations. A mathematical oddity appeared in his solution for the curved spacetime around spherically symmetric matter of mass

The so-called singularity at

Twenty years later, J. Robert Oppenheimer tried to make sense of gravitational singularities by analyzing the collapse of a spherical cloud of matter. He and his student Hartland Snyder were the first to realize the meaning of the second notable

Beyond that work, in the mid 1920s to mid 1950s, general relativity broadly was considered little more than a small correction to the Newtonian picture of gravitational interactions. 3 What’s more, the accuracy of general relativity compared with other proposed gravitational theories was still a matter of debate.

One prediction of Einstein’s theory, the bending of light by gravity, was confirmed by Arthur Eddington’s astronomical observations during the solar eclipse of 1919 (see the article by Daniel Kennefick, Physics Today, March 2009, page 37

Further experimental evidence for general relativity awaited advances in technology, and other unified field theories could explain gravitational light bending. Theoretical physicists instead turned their attention to quantum mechanics, which offered clear connections to experiments and plentiful potential applications.

Physics in the other renaissance

After World War II, what general relativity theorist Clifford Will called a “renaissance of general relativity” bloomed. 4 Physics had played a pivotal role in the war and in the Cold War that followed, and the result was that it enjoyed a boost in funding and an attraction of talent. The subsequent increase in postdoc positions helped transmit ideas in the previously small and geographically dispersed field of general relativity. The field eventually became well-defined, with regular conferences and publications devoted exclusively to it.

Recent high-precision instrumentation, such as lasers and atomic clocks, enabled tests of general relativity that hadn’t been feasible before. “As of the early 1960s the evidence supporting general relativity was thin at best,” says Will. “There was some, but it was pretty feeble.” With the ability to test aspects of gravitational theories, researchers regained interest.

After the discovery of quasars in the early 1960s, astronomers started to realize that general relativity might explain more than minor deviations from Newtonian theory. Quasars are apparently compact sources whose emissions change even on the scales of days or hours and are brighter than an entire galaxy. Their prodigious energy output couldn’t be accounted for in Newtonian gravity. Around the same time, Robert Pound and Glen Rebka’s gamma-ray experiments confirmed another prediction from general relativity: gravitational redshift.

On the theoretical front, mathematician Roy Kerr generalized Schwarzschild’s field-equation solution to a rotating body. And Martin Kruskal and David Finkelstein’s reexamination of the Schwarzschild result using different coordinates explained away the apparent singularity for a local observer at

Roger that

“Unlike most relativists, especially those in the US, Penrose came from a background in mathematics rather than physics,” says Rees. “That is why he had such distinctive influence in the 1960s.”

Penrose earned a degree in mathematics from University College London, where his father was a professor of human genetics, and went on to receive a PhD at the University of Cambridge in 1957. As a student Penrose was geometrical in his thinking, even compared to his peers in mathematics; for example, he formulated pictures as an alternative way to write complicated mathematical expressions, such as tensors. At Cambridge he attended lectures outside his field, notably those on relativity by Hermann Bondi and quantum mechanics by Paul Dirac.

During Penrose’s university years, his interest in astronomy increased due to Fred Hoyle’s BBC radio talks that covered astronomy and cosmology, including steady-state theory, which asserts that the universe is the same at any time and place. (Getting the theory to work in an expanding universe requires the constant production of new matter; see the article by Geoffrey Burbidge, Fred Hoyle, and Jayant V. Narlikar, Physics Today, April 1999, page 38

As a graduate student, Penrose also stumbled on the work of artist M. C. Escher. He was inspired to try his hand at similar, mathematically inspired designs, and he and his father devised their own impossible objects, some of which were published in the British Journal of Psychology.

5

One example, known as Penrose stairs, is shown in figure

Figure 1.

Roger Penrose plays with dimensions in his impossible stairs and spacetime diagrams. (a) Penrose stairs are one of the impossible objects Penrose designed with his father. Although such an object cannot exist as it appears in the image, with stairs ascending in a loop, real objects can create the illusion with a carefully selected shape viewed from the right angle. (Adapted from ref.

“It’s clear that he not only thinks very deeply, but in a very unusual and specially geometric way,” says Rees. “His notebooks look like those of Leonardo da Vinci!”

Finite infinities

As advances in experimental technology opened new views of the universe, so did theoretical tools. Among them, Penrose diagrams, published in 1962, were particularly powerful. 6 The diagrams are a visual representation of all spacetime, and after Sciama’s graduate student Brandon Carter helped popularize the diagrams, they became ubiquitous in black hole physics of the 1960s. They remain a standard in general relativity education and research.

The diagrams are derived from Hermann Minkowski’s 1907 depictions of spacetime with time as the vertical axis, one spatial dimension as the horizontal axis, and light traveling at 45°. Because an observer can’t travel faster than light, the spacetime available to them is defined by a 45° cone. But the meaning and interpretations of those diagrams weren’t well understood or agreed upon.

Physicists often consider the behavior of fields at infinity, but a point or observer at infinity doesn’t exist. Penrose found a way to concretize infinity through conformal transformations—that is, angle-preserving ratios of distances—of Minkowski space. After that transformation, infinity becomes the boundary of a finite region. “You can literally draw a universe,” says historian of science Aaron Wright, “and that was just not physically possible before that new technique.”

The infinite past I−, spatial infinities I0, and infinite future I+ transform into the point at the bottom, the ring at the center, and the point at the top right in figure

Penrose diagrams are similar in spirit to the puzzles and impossible objects Penrose designed with his father. As your eye moves around the diagram, the spatial relationships between you and the page change. For the diagram, the distance scales near the infinite edges appear dramatically smaller than at the center.

The drawings had “the same impact in our field as Feynman diagrams had in particle physics,” says Will. They didn’t just visualize what’s happening. The drawings are formal mathematical objects that can be used to perform calculations and obtain quantitative results without pages of equations.

It’s a trap

Diagrammatic analysis would serve Penrose well. In 1964 John Wheeler started reconsidering gravitational collapse and discussed the matter with him. Penrose approached the problem without assuming spherical symmetry or other idealized assumptions, as had been done previously.

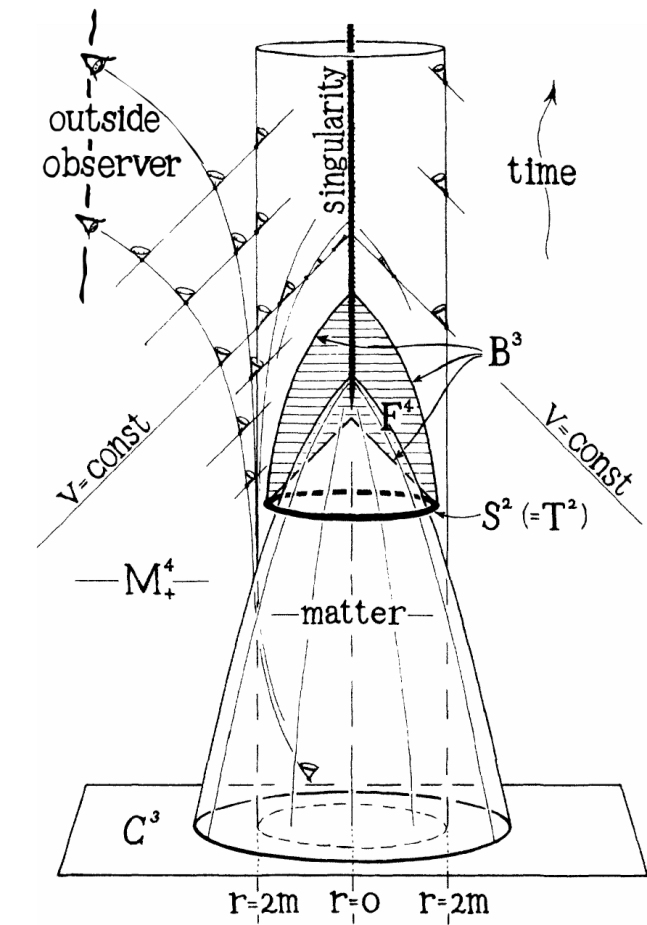

Penrose’s key insights, published in 1965, are summarized in figure

Figure 2.

Matter collapses into a black hole. As the radius

Penrose identified a point of no return—the formation of what he called a trapped surface—after which the collapse into a singularity, or black hole, is inevitable and unavoidable. From the collapsing matter’s perspective, once it is past the event horizon, it is surrounded by empty space, which hosts the trapped surface. In that bubble of spacetime, space and time dimensions swap properties: Space becomes timelike, and trajectories can move in only one direction. The existence of a trapped surface thus leads inevitably to a singularity.

A trapped surface forms even if the matter distribution lacks a sharp boundary, is asymmetric, or rotates. In fact, Penrose’s discussion of star collapse relies on few assumptions included in Einstein’s field equations; using a leading competitor gravitational theory of the time, posited by Carl Brans and Robert Dicke based on work by Pascual Jordan, wouldn’t qualitatively change his argument. Once enough mass occupies a given volume, pressure can’t counteract the gravity, and a black hole will form.

Causal effects

After Penrose’s analysis of gravitational collapse, black holes became the prevailing explanation for quasars. His research helped turn scientific opinion on black holes from unlikely theoretical entities to a plausible explanation of quasars, blazars, and other active galactic nuclei (for more, see the article by Neil Gehrels and Jacques Paul, Physics Today, February 1998, page 26

Penrose proceeded to elucidate the structure, dynamics, and nature of black holes. For example, in 1971 he realized that a black hole’s rotational energy could be physically extracted from the black hole. For any rotating mass, spacetime swirls around it. For the case of a rotating black hole, any observer cannot avoid rotating with that swirling spacetime. If a projectile swirling with spacetime splits in two such that one part escapes the black hole, the escaping part can have energy higher than the original projectile because of the black hole’s rotational energy.

Penrose also went on to collaborate with Stephen Hawking, a student of Sciama’s, and their application of similar trapped-surface reasoning to cosmological singularities supported the existence of a past singularity—the Big Bang.

“I think the Nobel Prize is long, long overdue” for Penrose and for general relativity, says theoretical physicist Lee Smolin. (Even Einstein won for the photoelectric effect, not general relativity.) Smolin emphasizes the influence Penrose has had on the mathematics used in general relativity, such as conformal structure.

With the recent high-profile results related to general relativity, such as the observation of gravitational waves (subject of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics; see Physics Today, December 2017, page 16

References

1. R. Penrose, Riv. Nuovo Cimento 1, 252 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02752493

2. R. Penrose, Phys. Rev. Lett. 14, 57 (1965). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.57

3. A. Blum, D. Giulini, R. Lalli, J. Renn, Eur. Phys. J. H 42, 95 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjh/e2017-80023-3

4. C. M. Will, Was Einstein Right? Putting General Relativity to the Test, Basic Books (1986).

5. L. S. Penrose, R. Penrose, Br. J. Psychol. 49, 31 (1958). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1958.tb00634.x

6. R. Penrose, Phys. Rev. Lett. 10, 66 (1963); https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.10.66

A. Wright, Hist. Stud. Nat. Sci. 44, 99 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1525/hsns.2014.44.2.99