The solar cycle and the Sun’s shape

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.0442

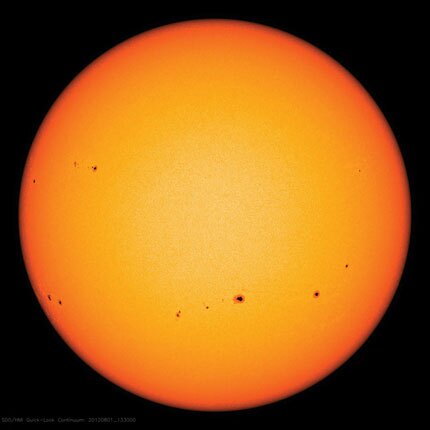

Like all spinning, fluid celestial bodies, the Sun is oblate. But its equatorial radius is just a few parts per million longer than its polar radius, which makes the solar oblateness very difficult to measure. Robert Dicke and coworkers tried hard half a century ago, hoping to find a departure from spherical symmetry large enough to reconcile Dicke’s alternative theory of gravity with the known precession of Mercury’s orbit. Later measurements made it clear that the Sun’s oblateness was much smaller than Dicke’s theory required. But inconsistency among the later measurements hinted at a variation of the oblateness that might be correlated with the 11-year cycle of sunspot abundance and other solar variables. Now a team led by Dicke’s former student Jeffrey Kuhn has used NASA’s orbiting Solar Dynamics Observatory