The physicist who took on Putin

Boris Nemtsov appears at a Moscow courthouse in 2014.

Ilya Schurov, CC BY 2.0

On 27 February 2015, Boris Nemtsov, the prominent Russian opposition figure, was in Moscow publicizing an upcoming rally against President Vladimir Putin’s maneuvering in Ukraine. After a late-night dinner, Nemtsov and his girlfriend were walking toward the city’s Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge when a car pulled up behind them. Nemtsov was shot four times and killed.

The assassination was especially shocking in the West because Nemtsov had been viewed as possible head-of-state material since the Boris Yeltsin years of the 1990s. Nemtsov’s political star had dimmed after Yeltsin brought in Putin to the top governing circle, yet he remained a dedicated democrat and emerged as a vocal and unintimidated critic of Putin. Earlier this month, the Washington, DC, city council voted to rename a street in front of the district’s Russian embassy after Nemtsov.

Little known outside of Russia is that Nemtsov was also a physicist, one who published an impressive 60 papers during a decade of research prior to his turn to politics. He came from a unique place for physics, Nizhny Novgorod (officially known as Gorky until 1990), the capital of the Volga Federal District in southeast Russia. Best known in the West as the place of exile for Russian physicist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Andrei Sakharov, Nizhny Novgorod also has a distinct history as a radiophysics center that evolved to become a crucible for nonlinear physics—the study of phenomena that experience amplified effects from stimulations. There, Nemtsov explored propagating phenomena across disciplines, in radiophysics, plasma physics, fluid dynamics, electromagnetic waves, and notably acoustics by creatively delving into the possibility of an acoustic laser.

“He had this agile vision of how to relate different phenomena that people didn’t really think of relating,” says Lev Tsimring, a University of California, San Diego, physicist who became friends with Nemtsov during their university days in Nizhny Novgorod in the 1970s. Nemtsov’s fast-moving mind distinguished him in the heady atmosphere of Soviet nonlinear physics, and Tsimring believes his friend would have been very successful had he remained in the field. But a post-Chernobyl protest, an outgoing personality, and perhaps the values and skills instilled in him by the physics world eventually prodded Nemtsov toward the career in politics that ultimately cost him his life.

Nizhny’s “beautiful science”

A bright and resourceful child who helped out his single mother by unloading milk from dairy trucks

Nemtsov attended Gorky Lobachevsky State University (now Nizhny Novgorod Lobachevsky University). Nemtsov’s mentors included Nikolai Denisov and Nemtsov’s uncle, Vilen Eidman, both physicists based at the university and affiliated with the Radiophysical Research Institute (NIRFI). Denisov and Eidman worked on plasmas, and Eidman, among other things, researched Cherenkov radiation with Vitaly Ginzburg

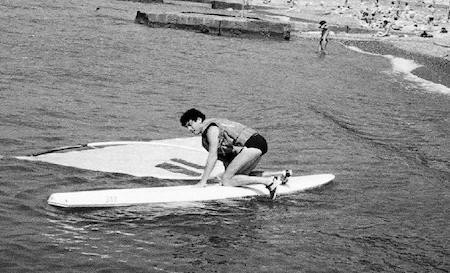

Nemtsov makes his first attempt at wind surfing in Sochi in 1986.

Margarita Ryutova

By the time of Nemtsov’s arrival, Nizhny Novgorod had already been a leading center for physics research for half a century. In the early 1930s, a group of young physicists was sent by the education ministry to Gorky to work on radiophysics. The newcomers included Aleksandr Andronov, a physicist who worked in applied mathematics and oscillations and was instrumental in bringing Ginzburg to chair the radiophysical faculty at Gorky University. Another early arrival in Nizhny, Maria Tikhonovna Grekhova, was named the director of NIRFI in 1956.

The interface of applied mathematics, in which Andronov was preeminently influential, and advanced radiophysics, especially with the work of Ginzburg, created a synergistic atmosphere at Nizhny Novgorod. The cross-pollination facilitated the signature Nizhny quest to understand the fundamentals of phenomena—waves and oscillations—that could be applied across physics subdisciplines. “One of our distinguishing features was that if you have an equation of a mathematical model, it could be the same for electromagnetics, acoustics, ocean waves, whatever,” says Lev Ostrovsky, a US-based physicist who taught in Tsimring’s and Nemtsov’s university department. “We also tried to have some qualitative understanding of a problem before going into complicated mathematics.”

The unique atmosphere of Nizhny Novgorod physics, his uncle’s mentorship, and a supportive pediatrician mother were fortuitous for Nemtsov. Tsimring recalls Nemtsov as a very energetic and enthusiastic student and a “work around the clock” researcher. He remembers talking with his friend about physics endlessly, including during their frequent tennis matches. Nemtsov was fond of recalling how he’d worked on his dissertation in his apartment’s bathroom, as the tiny apartment had little space for him, his wife, and his newborn child.

Prolific research

Nemtsov’s participation in prominent physics retreats and seminars in the Soviet Union helped him further his ideas and display his boldness as a physicist. In the mid 1980s he attended the selective Sochi Conference, an annual retreat at which veteran physicists, including Ginzburg, gathered with promising younger ones to discuss their research and challenge one another. The primary topic was nonlinear physics.

Ryutova recalls the vibrancy of the Sochi gathering. “We had the elite of nonlinear science in Russia,” she says. “There were the top-level people and young people, but the competition was quite high.” She believes it was Ginzburg who recommended that Nemtsov receive an invite. Sochi was also the site of Nemtsov’s first attempt at what would become a passionate avocation: wind surfing.

The Sochi Conference featured aggressive questioning, which Nemtsov naturally took to. Ryutova recalls Nemtsov’s high energy and competitive personality

Nemtsov (standing, third from left) attended the 1986 Sochi Conference, along with Margarita Ryutova (sitting, first from left).

Ryutova

Nemtsov deeply respected Ginzburg, and so he was honored to present at one of Ginzburg’s prestigious weekly seminars at the Institute of Physics of the Academy of Science in Moscow. There, Nemtsov and Tsimring explained a joint piece of research on the dynamics of the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability, in which a stationary fluid and a moving one interface. The research merged Tsimring’s interest in fluid dynamics with Nemtsov’s focus on the effects of various disruptive events.

After receiving his PhD-equivalent degree in 1985, Nemtsov continued working as a researcher at NIRFI. If there is a generalization one could make of Nemtsov’s engagement with physics, Tsimring suggests, it is that he was attracted to studying fast-moving objects that trigger perturbations and instabilities in the medium through which they travel. For example, Nemtsov authored a 1986 Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics study

Nemtsov churned out many papers in a short time. “He was probably one of the most interesting and promising young scientists at the time, at least at our institute and NIRFI,” Ostrovsky recalls. Although Ostrovsky says he sometimes had the impression that Nemtsov worked too fast on problems, the young physicist always approached them with originality.

Of all his research, it is Nemtsov’s theoretical work on an acoustic laser that best displays his depth and originality. The popular press picked up on that work, and Tsimring says Nemtsov was very proud of it. An acoustic laser is a sound wave that, similar to a laser, self-synchronizes, producing an amplification in a dense medium.

Nemtsov did not invent or conceive of the acoustic laser, but he devised an original version in which water vapor is the disequilibrium medium through which an acoustic amplification occurs. Nemtsov demonstrated that putting water vapor between acoustic mirrors will cause sound waves to bounce back and forth and create a resonance, just as in a traditional electromagnetic laser.

Although Nemtsov did not experimentally demonstrate his acoustic laser concept, it may have influenced similar, current work on sasers: sound amplification by simulated emission of radiation. While Nemtsov’s proposed device was classical in nature, sasers are quantum, according to Ostrovsky, with potential applications in information transmission.

Shifting to politics

Nemtsov’s transition from physics to politics began in the late 1980s, when he emerged as a strong voice in a local effort opposing a proposed nuclear power plant in Nizhny Novgorod. City officials put forward the plant as a way to heat the water that circulated throughout the city to heat apartment buildings. It didn’t take a physicist to realize that there were risks involved. “Circulating mildly radioactive water through people’s homes would create an unimaginable health hazard,” says Tsimring. “And in the case of a nuclear accident similar to Chernobyl, a 30 km exclusion zone would include the whole city of Gorky, with its 1.5 million inhabitants.”

Lev Tsimring (right) visited his old friend Nemtsov in Moscow in 2003.

Tsimring

As with so many, the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986 was a big jolt for Nemtsov, and Ryutova recounts his talking about it while he was still uninterested in politics. But the Nizhny Novgorod nuclear plan was the turning point, in no small measure because Nemtsov’s mother led the early protests.

Once he was engaged in politics, the combination of physics knowledge and social skills propelled Nemtsov to be the opposition’s leading voice. “He was interested in it from the physics standpoint: How safe is it to operate? What are the factors that can affect the safety of this plant?” says Tsimring. “Physics helped him to get people’s attention and trust, and he went from there.”

One of the places it took him to was a one-on-one meeting with Sakharov, which Nemtsov recorded and published as an interview. Sakharov supported the effort―ultimately successful―to kill the nuclear plant plan.

Through the antinuclear campaign, Nemtsov got the bug for politics and gained the attention of progressives. But he was torn about abandoning physics for politics. Tsimring recalls conversations with Nemtsov as he considered what he should do. Ultimately, Tsimring believes that Nemtsov’s outgoingness, energy, and optimism over the future of what was then the Soviet Union inclined him to politics and public service during the Yeltsin era.

Once he made the commitment, Nemtsov quickly ascended in politics, representing Nizhny Novgorod in the national parliament, then serving as its governor, and eventually becoming one of Yeltsin’s deputy prime ministers in Moscow. Tsimring notes that in many ways Nemtsov’s focus within physics—fast-moving objects causing disruptions—was an apt metaphor for his approach to politics. “When he moved through people’s lives, the effect he created was like a sonic boom,” Tsimring says. “He was a very active, fast-moving person.”

With Putin’s ascendancy, Nemtsov became a vocal opposition figure. How much of his motivation came from his physics background is speculation. Ostrovsky, Ryutova, and Tsimring all say that a part of their physics world’s ethos at the time was a yearning for culture and freedom of inquiry, so it’s likely that at least a part of Nemtsov’s fearlessness came from his experiences in the field. “Not all physicists are so brave,” says Ostrovsky. “But he was very brave. We tried to do something in the spirit of dissidence, but not so actively as Boris.”