The most energetic supernova conceivable?

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.3096

When a white dwarf accretes too much material or a massive star expends its nuclear fuel, the star’s death throes yield an explosion—a supernova—so intense that it often outshines the star’s host galaxy. Within the past several years, astronomers have recognized a new class of supernovae: superluminous supernovae (SLSNe), which can outshine their conventional siblings by a factor of 100 or more. 1

The most radiant SLSN of all was spotted last June by the Ohio State University–led All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN, pronounced “assassin”), according to an analysis by an international team led by Subo Dong (Peking University) and Krzysztof Stanek (Ohio State). 2 The object, dubbed ASASSN-15lh, has double the luminosity of the runner-up SLSN. And it’s a rather mysterious beast indeed.

Family ties

Traditionally supernovae are found in targeted searches: Observers look for the abrupt appearance of explosions in a specific set of large galaxies that are periodically reexamined. That approach, says Stanek, can bias the kind of supernovae that are discovered. A bit more than a decade ago, the Texas Supernova Search tried a different approach. Led by Robert Quimby, then a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, the survey team continuously monitored a single patch of sky. In that way, it could spot not only supernovae in large, known galaxies but also those erupting in galaxies too faint to otherwise notice. Inspired by that concept, Stanek and colleagues decided to scan as much of the sky as possible as often as possible to look for supernovae and other transient objects.

Currently ASAS-SN deploys eight 14-cm telescopes, four in Hawaii and four in Chile; two of the eight are shown in figure 1. Were it not for the Sun, they’d be able to monitor the entire sky; in practice they cover three-fourths of it. When the weather cooperates and all systems are go, ASAS-SN can complete a search in 48 hours.

Figure 1. The All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae repeatedly scans much of the night sky, looking for transient objects. Two of the survey’s eight 14-cm telescopes appear in the foreground of this photo. (Photo credit: Wayne Rosing, Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network.)

Survey telescopes recorded ASASSN-15lh three weeks before researchers noticed it in the data. Once the ASAS-SN team recognized that it had something worth further study, however, it quickly verified its images with telescopes from the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network, which, Stanek emphasizes, has been an instrumental partner from the beginning of the project. Optical spectra were then procured with several large, ground-based telescopes; the Swift satellite provided additional optical and UV images. Data collection continues to this day.

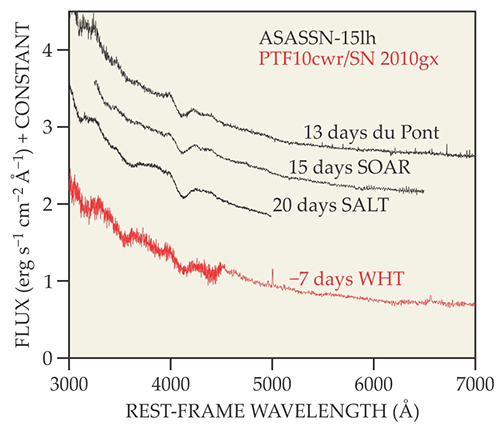

The follow-up spectra were mostly featureless, but they contained a broad absorption trough near 5100 Å in the lab frame. A similar trough had been spotted earlier by the Palomar Transient Factory and Pan-STARRS (Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System) surveys in a SLSN named PTF10cwr/SN 2010gx. Based on those previous observations, the ASAS-SN researchers concluded that the trough in the ASASSN-15lh spectra was due to ionized oxygen, which has an emission line near 4100 Å in its frame. Thus they tentatively assigned a redshift of 0.23 to their newly observed object. As figure 2 shows, given that assumption, the spectra of ASASSN-15lh and PTF10cwr/SN 2010gx match up well. Follow-up observations spotted sharp, characteristic magnesium lines that yielded a redshift of 0.2326. With the initial redshift deduction confirmed, the ASAS-SN team concluded that the object it spotted last June was indeed a supernova. And once the researchers knew its redshift and apparent brightness, they could calculate its record-breaking luminosity.

Figure 2. Optical spectra of ASASSN-15lh taken by three optical telescopes (black) all resemble the spectrum (red) of the superluminous supernova PTF10cwr/SN 2010gx. Wavelength and times in days relative to the moment of peak brightness are given in the frame of the exploding objects. Spectra, displaced for ease of viewing, were taken at the du Pont 2.5 m telescope, the Southern Astrophysical Research Telescope (SOAR), the South African Large Telescope (SALT), and the William Herschel Telescope (WHT). (Adapted from ref.

Give it a whirl

Not only is ASASSN-15lh bright, it has by now radiated a jaw-dropping 1052 ergs (1045 J) of energy. The engines that power most supernovae and even SLSNe do not seem to be operating for ASASSN-15lh. When white dwarfs explode into supernovae, they incinerate carbon and nitrogen into nickel-56. Radioactive decay of that isotope can provide a great deal of energy. But the 1052 ergs radiated in just a few months by ASASSN-15lh would require an implausible 30–50 solar masses of 56Ni. When a spent massive star gravitationally collapses, it generates an outward propagating shock wave that can heat circumstellar material and, in principle, account for the enormous energy radiated by ASASSN-15lh. In general, however, circumstellar material is hydrogen rich, and hydrogen features are conspicuously absent in the ASASSN-15lh spectra.

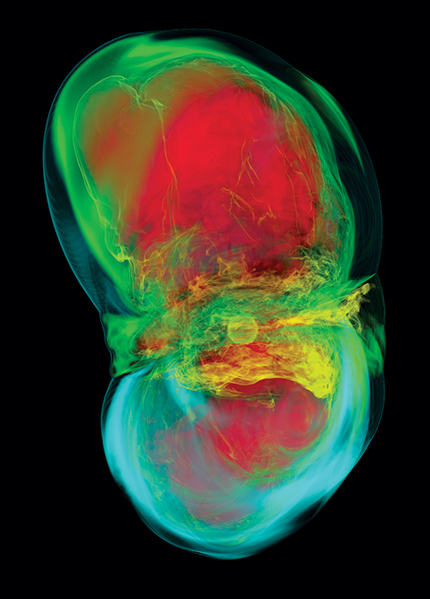

At least in terms of energy, ASASSN-15lh could be a star being tidally disrupted by a black hole or a manifestation of a star made from quarks. Perhaps the most promising explanation for its prodigious output posits that the remnant of ASASSN-15lh is a magnetar such as shown in figure 3, a spinning neutron star with a magnetic field of some 1014 G (see Physics Today, May 2005, page 19

Figure 3. A magnetar is a spinning neutron star with an extremely large magnetic field. This supercomputer simulation shows a supernova explosion powered by a magnetar. Different colors correspond to gas of different temperature. Blue represents the coldest gas; red, the hottest. The rendering spans 3000 km, top to bottom. (Simulation frame courtesy of Philipp Mösta, University of California, Berkeley, and Sherwood Richers, Caltech.)

Magnetars have been observed in the Milky Way; they are not speculative objects. But the ones in our galaxy are spinning with a leisurely period of about 10 seconds. To have enough rotational energy to power ASASSN-15lh, a magnetar would have to spin with a millisecond period. Astronomers have never seen a millisecond magnetar, possibly because any magnetar born with such a short period would lose the bulk of its rotational energy in just a few months. Moreover, theorists recognize, a millisecond magnetar is spinning so rapidly that it is on the verge of centrifugally blowing itself apart. The magnetar model seems capable of explaining ASASSN-15lh, but just barely. If the object is a magnetar-powered SLSN, it may be almost literally the most energetic supernova conceivable.

Further oddities

Beginning in September, observations of ASASSN-15lh have revealed an unexpected increase in its power output and temperature. Much of the new power is in the UV. Magnetar theorist Brian Metzger notes that the neutral ejecta of a supernova are opaque to UV radiation, but in time they could be ionized, which would allow the UV to escape. It’s too early to tell if the new bump in intensity has anything to do with that theoretical ionization breakout.

Most of the two dozen known SLSNe have been spotted in dwarf galaxies low in metals—that is, elements other than hydrogen or helium. But ASASSN-15lh was seen against a large metal-rich galaxy. As ASASSN-15lh fades and its host environment comes into better view, we might learn that the object was actually born in a currently invisible dwarf galaxy. But for now, the host of ASASSN-15lh represents a mystery.

For his part, Stanek relishes his role in contributing to a scientific puzzle. “I’m an observer, not a theorist,” he says. “I’m very happy we found something super unusual, but whatever the data tell us, we will listen.”

References

1. R. M. Quimby et al., Nature 474, 487 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10095

2. S. Dong et al., Science 351, 257 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac9613

3. D. Kasen, L. Bildsten, Astrophys. J. 717, 245 (2010); https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/717/1/245

S. E. Woosley, Astrophys. J. Lett. 719, L204 (2010).https://doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/719/2/L204