The award rejection that shook astronomy

In the early 1970s Margaret Burbidge

Margaret Burbidge in 1973, two years after she rejected the Annie Jump Cannon Award.

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, John Irwin Slide Collection

In a letter to AAS secretary Laurence Frederick, Burbidge wrote, “I believe that it is high time that discrimination in favor of, as well as against women in professional life be removed, and a prize restricted to women is in this category.” Underlying that official statement was the suspicion that the Cannon Award had kept women from receiving other recognition. In conclusion, Burbidge wrote, “It would be interesting to know, however, how often our names have been excluded from consideration for professorships, directorships … because we are women.”

At that time, AAS offered two other awards—the Henry Norris Russell Lectureship, which honored an astronomer’s long and distinguished career, and the Helen B. Warner Prize, for astronomers no more than 35 years old. No woman had received the Russell. Burbidge was the only woman to have won the Warner Prize, in 1959, and she had shared it with her husband Geoffrey for their work on stellar nucleosynthesis.

Margaret Burbidge’s startling refusal resulted in not only a decades-long change in the Cannon Award’s administration, but also the creation of the first working group on the status of women in astronomy. In the long run, her decision led to increased awareness in the astronomy community of discrimination against women and other minority groups.

An award and a brooch

Annie Jump Cannon

Annie Jump Cannon established an award for women astronomers in 1933.

Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image # SIA2008-0646

The news of Burbidge’s refusal, which quickly reached the astronomical community, presented an image crisis for AAS. In response, the AAS Council established the Special Cannon Prize Committee and charged it with recommending a course of action. The members were chairman George Preston

Letters solicited from the community ranged from expressions of anger and hostility to support for change, with a strong correlation to the age of the writer. Even within the committee, our suggestions ran the gamut: don’t change the award, abolish it, open the award to both men and women, upgrade it to equal the Russell Lectureship, along with other ideas.

Among the factors we had to consider was how the Cannon Award winners would be recognized. The Russell Lectureship and Warner Prize each included a prestigious lecture at an AAS meeting, a large engraved certificate, and a financial award. Hogg described to the committee the contrasting presentation of the Annie Jump Cannon Award: The recipient would stand up at the society banquet to polite applause to receive the award plus a pin or brooch. As related by Dava Sobel in her 2016 book, The Glass Universe

By mid 1972, the committee had not reached any consensus. In his May 1972 progress report, Preston described the situation as a Pandora’s box: “Two women wanted to open the award to men and women or abolish it, two women to keep it as is or abolish it, and the three men sat on the fence.” He was not optimistic about a resolution but called a meeting of the committee at the AAS gathering in August.

At the summer meeting, the committee coalesced around a suggestion by Peery to transfer the administration of the Cannon Award to the American Association of University Women (AAUW). We also recommended that the Cannon Award continue to be used to encourage research in astronomy by women and that it be based on a competition, like that for a fellowship or research grant, among applicants in the early stages of their careers. We suggested that applicants submit a research proposal and a statement of how the funds would benefit their work.

Margaret Harwood received this galaxy-shaped gold pin when she won the Annie Jump Cannon Award in 1962.

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Despite the curious decision by AAS president Martin Schwarzschild that committee members not speak at Preston’s presentation to the AAS Council, the society’s governing body accepted our recommendations. In 1973 AAS transferred the award to the AAUW.

Twenty-four young women received the Annie Jump Cannon Award from 1974 to 2004. In 2005 AAS reassumed responsibility when the AAUW could no longer support it. Another ad hoc committee was appointed to decide on the guidelines for the award. The group’s minutes have a certain déjà vu, with many of the same arguments we had in 1972. The Cannon Award is now based on outstanding research and promise for the future. It is given to a North American woman astronomer within five years of receiving her PhD. It now includes a talk at an AAS meeting.

Bigger implications

Although the charge of the 1972 committee was to focus on the Cannon Award, our second recommendation proved even more important in the long term. Because “the problem of women in professional life transcends the disposition of the AJ Cannon Award which is only the tip of an iceberg,” the committee concluded, “we recommend that the AAS sponsor a working group on the status of women in astronomy.” Our recommendation was accepted.

Membership in the working group was voluntary, with an elected executive committee chaired by Cowley with Beverly Lynds

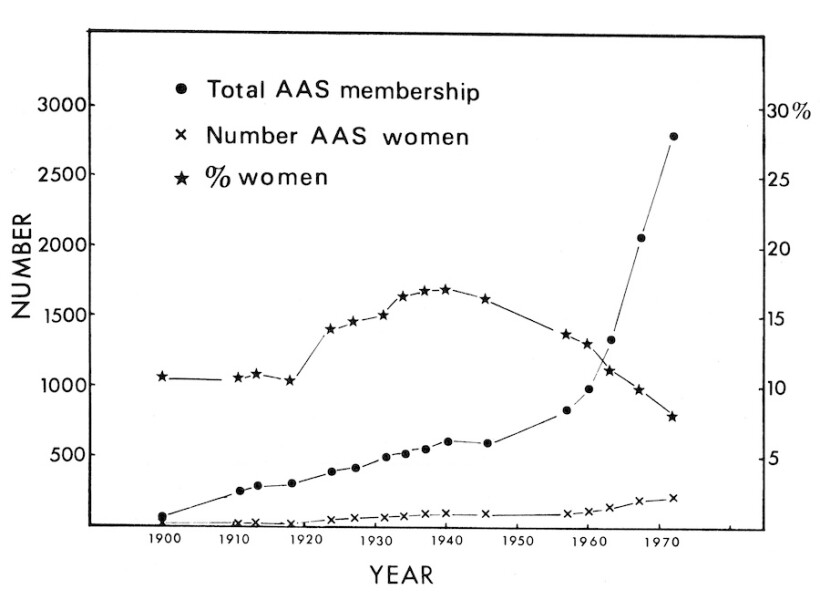

A 1973 survey of astronomers found that although the number of women in AAS had gradually increased from 1900 to 1973, female representation as a percentage of total membership had actually decreased beginning around 1940.

BAAS

Our report included a roster of 166 women members to encourage their consideration for society offices, committee appointments, prizes, lectureships, speaking engagements, and journal editorships. We also recommended adoption of affirmative action policies, an end to nepotism, and equal pay for equal work.

| 1972–73 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Full professor | 2% | 15% |

| Associate professor | 5 | 29 |

| Assistant professor | 2 | 29 |

| Other | 15 | 22 |

The AAS Committee on the Status of Women in Astronomy

As for awards, five women have received the Russell

Clearly there has been progress, but more is needed in hiring, promotion, salaries, and recognition. That applies not only to women but also to other underrepresented groups. Over the past two decades, AAS has established the Committee on the Status of Minorities in Astronomy

I had my own Burbidge/Cannon moment in 2001 when the University of Minnesota established a Distinguished Women Scholars Award. Len Kuhi, the chairman of our small astronomy program, asked if I’d like to be nominated. I gave this some thought and said, “Thanks Len, but I’m going to pull a Margaret Burbidge on you. I want to be nominated for the Distinguished Professorship.” No woman had received this honor in the College of Science and Engineering. Somewhat later, the dean, Ted Davis, emphasized to me that it was “a very prestigious award, the college’s highest honor, and only the best faculty receive it.”

A few months later, I got the award. At the ceremony, Davis whispered to me, “I’ll never forget what you did.” A year later I was his associate dean. Today four of the 18 Distinguished Professors in our college are women. As Burbidge showed by example 47 years ago, sometimes we have to be our own advocates.

Although there is still work to be done, Margaret Burbidge’s rejection of the Cannon Award and its consequences, including the first report on the status of women in astronomy, marked the beginning of increased awareness by AAS of obstacles and discrimination against women and other underrepresented groups.

Roberta M. Humphreys