Suborbital research hitches a ride on commercial space cruisers

DOI: 10.1063/1.3502543

Even with its budget in limbo, last month NASA awarded $475 000 to two commercial rocket makers through its Commercial Reusable Suborbital Research (CRuSR) Program, which pays to fly scientific experiments to the edge of space and back. The grant will allow Texas-based Armadillo Aerospace and California-based Masten Space Systems, who will split the award, to launch test flights in the coming months that will haul position- and velocity-monitoring antennas and environmental sensors supplied by the Federal Aviation Administration and NASA.

The promise of frequent, relatively inexpensive flights to suborbital space has attracted a growing number of researchers who are poised to send, or even accompany, experiments on multi-use commercial spaceships. The fledgling commercial space sector is now testing manned and unmanned rockets that could cruise for three or more minutes in a steady-state, low-vibration microgravity environment at altitudes around 100 km. Commercial space vehicles can take an experiment to space and bring it back at far less cost than conventional unmanned, single-use NASA rockets or a trip to the International Space Station, if one can even be arranged.

Science in the “ignorosphere”

Last month’s award has energized the growing hybrid community of microgravity scientists and commercial space-vehicle developers, which eight months before had held the inaugural Next-Generation Suborbital Researchers Conference in Boulder, Colorado. That conference sprang from a workshop convened by NASA at the December 2008 American Geophysical Union meeting; workshop attendees discussed an array of environmental data that could be collected and experiments that could be conducted in the mesosphere, which is 50-100 km above Earth.

That region gets called the ignorosphere “because we’ve ignored it for so long in terms of atmospheric observations,” says Bretton Alexander, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, which coordinated the conference in February. Besides climatology, Alexander says, a scientist in a manned suborbital vehicle “can look up at stars and do astronomy. You can look down at the Earth with hyperspectral sensors. You can test out orbital space technology in a very inexpensive way.”

“With three minutes, you can study transient behavior of entire systems and not just components,” says Purdue University aeronautics researcher Steven Collicott, whose experiment on critical surface wetting in microgravity was one of three selected for a free trip on an upcoming suborbital test flight by Blue Origin, an aerospace company in Kent, Washington. Another project chosen was an experiment by Louisiana State University chemist John Pojman on fluid mixing induced by interfacial tension. In the third, University of Central Florida astrophysicist Joshua Colwell will use dust-particle collisions to study accretion efficiency in the early stages of the solar system’s formation. Colwell says more frequent access to space will benefit scientists and educators in general: “The broader scientific community and educators need to know that there will be relatively inexpensive launches to high altitudes in a year or two.”

Seed-corn investments

The CRuSR program is seeking $15 million annually through 2015 as part of a $572 million request in the Obama administration’s fiscal year 2011 NASA budget for the establishment of an Office of the Chief Technologist. Charged with managing space technology programs, the office will provide awards to inventors for ideas ranging from pie-in-the-sky to flight-ready technologies, such as the commercial suborbital rockets. Programs include NASA’s Centennial Challenges, which are open to the citizen-inventor; new academic research grants and fellowships in space technology; and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program.

Over the past decade NASA’s pace of discovery has slowed, says Robert Braun, the space agency’s chief technologist. “NASA has not made the seed-corn investments in research and technology required to take grand steps in exploration, aeronautics, and science missions. By investing a small portion of NASA’s budget, we will enable much grander missions in the future.”

Braun says he’s optimistic that the space technology programs will be funded in an otherwise controversial budget, which includes the president’s plan to cancel or scale back the over-budget and tardy Constellation Program to build the space shuttle’s replacement. Constellation’s grounding could lead to a loss of jobs and would delay human exploration of the Moon or Mars. At press time, Congress was in the process of reconciling different versions of the NASA authorization bill passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate, both of which proposed funding CRuSR at its requested level.

Although the space technology programs have enjoyed a relatively warm reception from members of Congress, the Commercial Spaceflight Federation and NASA aren’t taking any chances. They have rallied support from notable members of the space community, who together with 14 Nobel laureates—10 of them physicists—wrote a letter in August to members of the House praising the president’s plan to “revitalize NASA’s investments in technology, commercial spaceflight, student research, and robotic exploration precursors.”

The CRuSR funding is a relative drop in the bucket, but that small investment is being held up as one example of how commercial space vehicles can serve national science interests and not just taxi wealthy tourists into space and back. A trip to suborbital space will cost a 100-kg tourist or science experiment between $100 000 and $200 000, says Armadillo Aerospace vice president Neil Milburn. “Our gut feeling tells us that the scientific-payload market is probably as large as, if not larger than, the market for space tourists.”

Training the scientist-astronaut

Although CRuSR has no plans to fund human flight, suborbital training classes are gaining in popularity. The National Aerospace Training and Research (NASTAR) Center in Pennsylvania is offering scientists who would like to accompany their experiments into space a rundown on the physiological stresses they may encounter. In particular, NASTAR trains scientists to focus on their experiments and not be distracted by “that pretty view outside the window,” says NASTAR graduate and planetary scientist Daniel Durda, who analyzes airborne observations of planetary and asteroidal occultation events at the Southwest Research Institute.

Alternatively, a researcher could hire a NASTAR-trained scientist-astronaut, says geophysicist Brian Shiro, who started the nonprofit Astronauts4Hire to recruit aspiring astronauts to run science experiments on commercial flights. “Our 17 members are a mix of established professionals and students pursuing graduate degrees in a range of science and engineering fields,” says Shiro. One potential Astronauts4Hire customer may be NASTAR-trained Collicott, who says that in space he’d rather be a tourist than a scientist. “If I’m ever up there,” he says, “I want to look out that window.”

Aerospace engineering students from Purdue University get to see their experiment—to study the effects of a reduced-gravity environment on liquids of different masses—take flight on a suborbital rocket, behind on the left, at Armadillo Aerospace’s facility in Rockwall, Texas. From left to right are Russell Hammer, Jeremy Voigt, Jeremy Smith, and Jake Bills.

STEVEN COLLICOTT/PURDUE UVIVERSITY

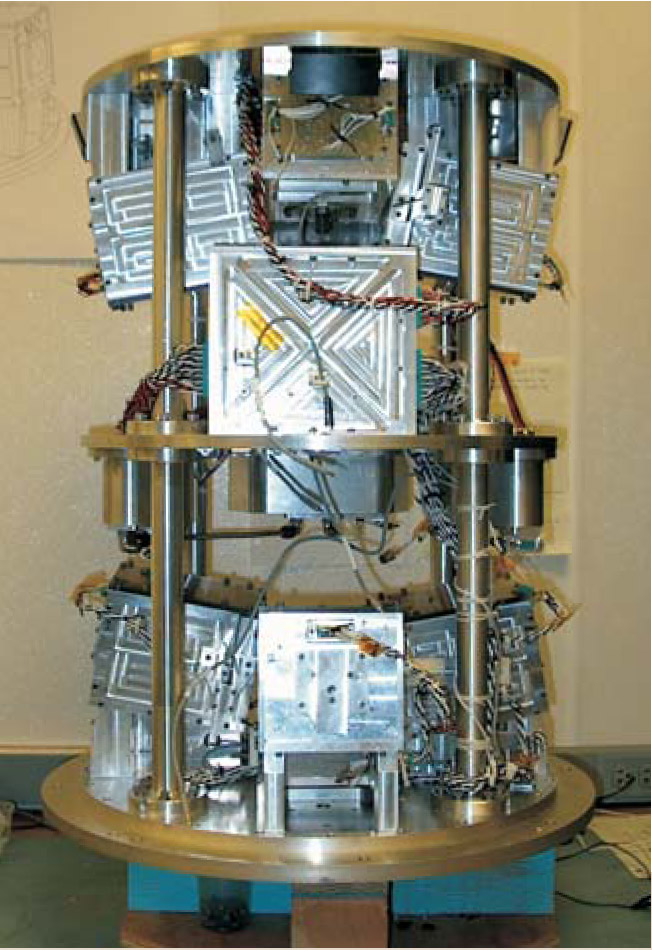

The Collisions Into Dust Experiment, which studies gentle collisions (slower than 1 m/s) between small particles in a microgravity environment, is being modified from its space shuttle configuration to one that allows it to fly on a commercial suborbital rocket.

Joshua Colwell