Spectroscopy for pions

Laser spectroscopy of atoms and simple molecules allows for some fantastically precise measurements. The best optical clocks, based on atomic resonances, lose less than a second in the age of the universe. Precision spectroscopy is being used to search for drifts in fundamental constants over time and deviations from Newtonian gravity over short distances (see Physics Today, October 2019, page 18

To bring spectroscopic precision to a broader range of fundamental physics problems, researchers create exotic atoms by replacing one or more of the particles in an ordinary atom with a different particle of the same charge, such as a positron, muon, or antiproton. By studying the spectrum of antihydrogen

Masaki Hori

Mesons are quarks bound to antiquarks, and the negatively charged pion is a down quark bound to an up antiquark. It almost always decays into a muon and a muon antineutrino. From the energy balance of that reaction, one could establish a valuable constraint on the as-yet-unknown neutrino mass states—except that the pion mass isn’t currently known with sufficient precision. Because an atom’s spectroscopic resonances depend on the masses of its constituent particles, spectroscopy of a pion-endowed atom could help.

Charged pions decay via the weak interaction, and their relatively long lifetime of 26 ns is plenty of time to make a spectroscopic measurement. In the confines of an atom, however, a pion can react with a nucleon via the strong interaction; the reaction destroys the atom—and the pion—in picoseconds or less. But if the pion is deposited into an orbital with high angular momentum, it’s kept away from the nucleus, and the resulting atomic state can persist for almost as long as the pion itself. The illustration above shows such a state of a so-called pionic helium atom: a helium nucleus (red and green), a single electron (blue), and a pion (black) orbiting the nucleus at a distance.

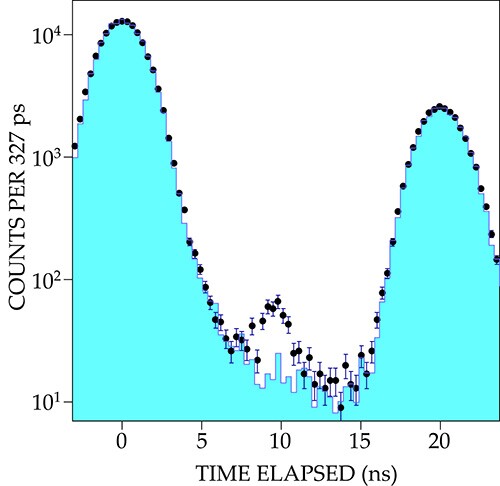

The exotic pion-endowed helium atoms were created at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland, where the researchers smashed a pulsed pion beam into a liquid helium target. Some 98% of the nascent pionic atoms were created in short-lived states that decayed immediately, and their fission products are detected in real time, as shown by the light blue histogram in the figure below. The remaining 2% were formed in high-angular-momentum states that survived for longer.

Figure adapted from M. Hori et al., Nature 581, 37 (2020)

The researchers irradiated the target with laser pulses interspersed between the pion pulses. When the laser frequency coincided with an atomic resonance of the pionic helium atoms, it excited the lingering atoms out of their long-lived state and into a short-lived one; their decays show up as the small peak at 10 ns in the black data points in the figure.

But there was a problem. The laser frequency that produced that signal was 0.04% greater than the expected resonance frequency, as calculated from the best available value for the pion mass. The researchers attribute the blueshifting to collisions among atoms in the liquid helium; a precision measurement of the pion mass will have to wait until they get a better handle on that effect. Their plan: Swap out the liquid helium target for a gaseous one, then measure the resonance shift as a function of gas density. (M. Hori et al., Nature 581, 37, 2020

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org