Solid Helium-4 in Bulk Doesn’t Go With the Flow

DOI: 10.1063/1.1839368

Suppose you could freeze the water in a washing machine while it was operating. Once the water had solidified, the machine’s agitators would cause the entire icy mass to oscillate—until the motor burned out. In January of this year, Eun-Seong Kim and Moses Chan, both at Pennsylvania State University, reported an experiment

1

that has some of the flavor of the washing-machine fantasy, but which yielded a surprising result (see Physics Today, April 2004, page 21

The 4He, though, was embedded in Vycor glass, a highly porous material with a pore size just several nanometers across. That porous structure, with its large surface area, complicated the interpretation of the decrease in oscillation period. A conceptually cleaner experiment would use a torsion oscillator that contains an annular channel filled with solid 4He. Kim and Chan have now done that bulk-helium experiment, 2 and the results are much like those of the earlier Vycor work and a subsequent similar experiment with porous gold. “Kim and Chan are clearly seeing something really fascinating,” says Robert Hallock of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “I’m not sure what it means yet, but I trust their observations.”

Getting in the groove

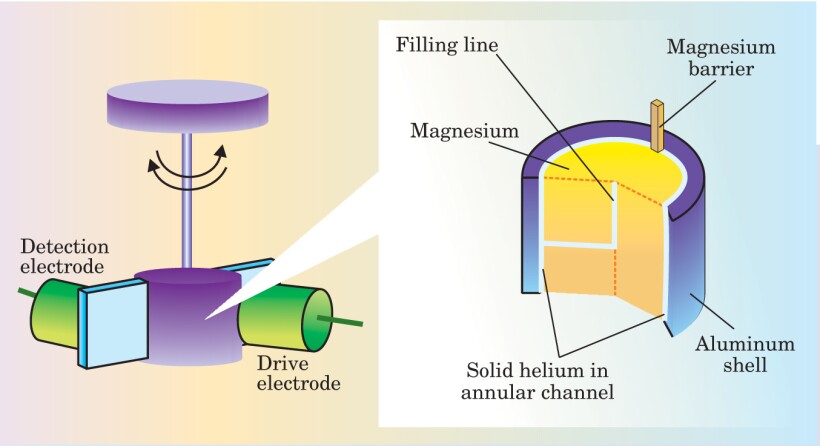

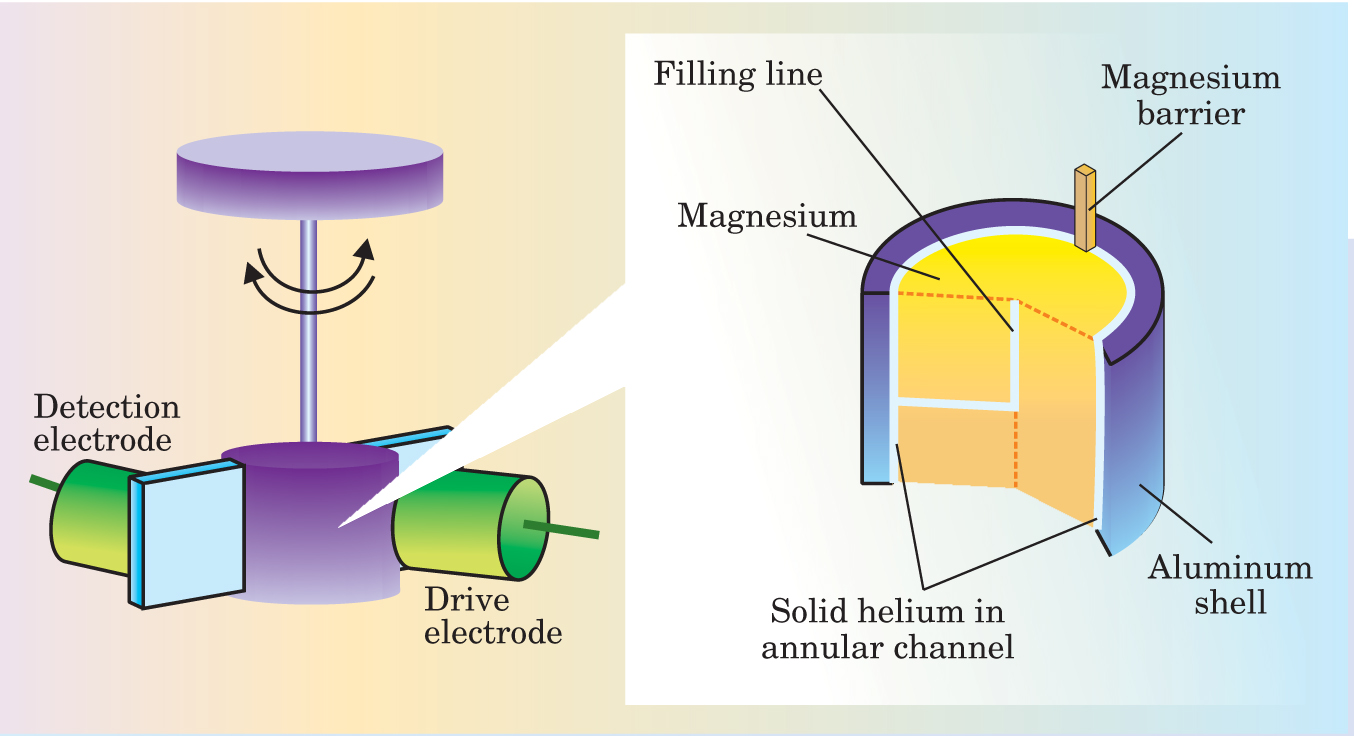

In their bulk-helium experiment, the Penn State researchers introduced liquid 4He into a narrow annular channel near the outside of the torsional oscillator illustrated in figure 1, and solidified the 4He at high pressure. They then electrically drove the oscillator and measured the resonant period as they lowered the temperature of the solid; by changing the driving voltage, Kim and Chan adjusted the oscillation amplitude and thus the maximum speed of the channel.

Torsion oscillator. Solid helium occupies a 1-cm diameter annular channel in a cylindrical cell suspended by a torsion rod. With the help of the electrodes attached to the side of the cell, a lock-in amplifier can keep the oscillator in resonance. The superfluid behavior observed in the cell goes away when a magnesium barrier blocks the channel.

(Courtesy of Eun-Seong Kim and Moses Chan.)

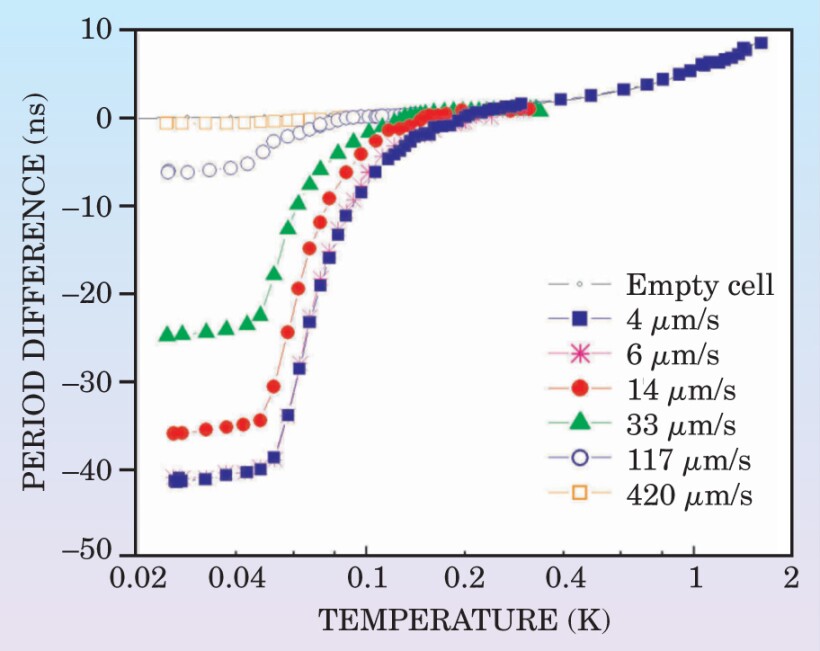

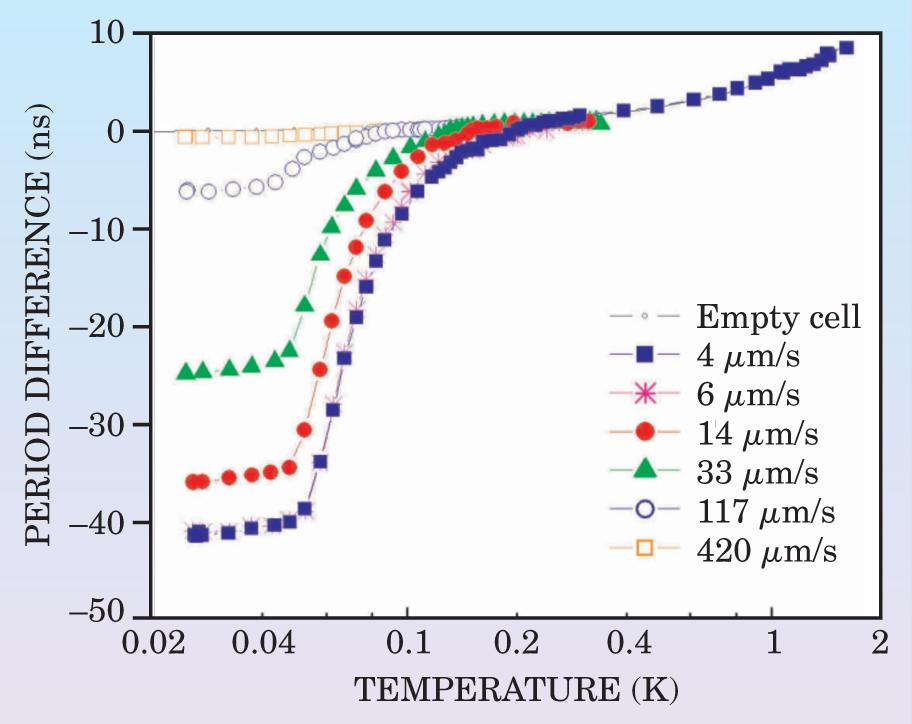

As figure 2 shows, the resonant period began to decrease as the temperature fell below about 250 mK. The period drop was most pronounced for small maximum speeds and seemed to saturate below 5 µm/s or so. The drop in period indicates a corresponding drop in the moment of inertia of the material in the cell’s annular channel. Presumably, some of the solid material had decoupled from the bulk. That so-called supersolid was not participating in the overall oscillatory motion. When a magnesium barrier was introduced into the oscillator to block the annular channel, the change in period was reduced by a factor of about 60.

A decrease in period at low temperature. When an oscillator with an annular groove containing solid helium is cooled below 250 mK, the period decreases. (The period difference is defined relative to the period at 300 mK.) That decrease implies a drop in the moment of inertia—apparently some of the solid is not participating in the general oscillation. At lower temperatures, the drop in period increases as the maximum speed of the helium decreases. For this experimental run, the pressure of the helium was 5.1 MPa. Experiments at a variety of pressures suggest that the period drop saturates below about 5 µm/s.

(Courtesy of Eun-Seong Kim and Moses Chan.)

The observation of an apparent decoupling in the bulk solid answers a major concern that had been raised about the earlier experiments with porous media. Particularly in the tiny-pored Vycor, it was not clear what formed in the pores. One possibility was that a fluid layer lined the pore surfaces and was masquerading as a supersolid. Such a fluid layer may have been present in the bulk experiment too, but with a thickness of just an atom or two, it couldn’t have been responsible for the observed drop in period.

Conversely, the results in Vycor strengthen the interpretation that the bulk-helium observations were caused by the decoupling of a solid component from the bulk. The University of Alberta’s John Beamish points out that, absent the Vycor results, the decoupling might have had a more conventional explanation because solids are not entirely rigid and sometimes can deform. If one rotates a cup of coffee back and forth, Beamish points out, the coffee—a conventional viscous liquid, not a superfluid—does not rotate as quickly in the center of the cup as it does near the edge. If a similar effect were to occur with the solid 4He in the oscillator’s annular channel, it could mimic decoupling. But that explanation is not compatible with the observed decoupling in the small pores of Vycor; all the coffee confined within a thin capillary will rotate together.

The drop in the bulk helium’s moment of inertia can be explained without invoking macroscopic supersolid flow. Anthony Leggett of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign notes that one can’t rule out the possibility that Kim and Chan are observing a nonequilibrium phenomenon with a relaxation time greater than the 1 ms period of their oscillator. And Nikolay Prokof’ev and Boris Svistunov (both at UMass) have suggested that the material that decouples is restricted to the crystalline boundaries that form as 4He freezes.

But a supersolid component in the bulk is a plausible interpretation of the Kim and Chan observations. What can be responsible for the decoupling of a solid component? In an article commenting on the bulk-helium experiment, Leggett offers three possibilities—vacancies, large defects such as dislocations, and quantum-mechanical exchange associated with atomic wavefunction overlap. 3 All three possibilities have their problems.

No support from pressure

A 2002 experiment conducted by John Goodkind at the University of California, San Diego, inspired Kim and Chan’s explorations. That experiment was interpreted in terms of a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) in solid, bosonic 4He, mediated by vacancies or dislocations that were thermally activated at temperatures above 200 mK. Some 30 years earlier, Alexander F. Andreev and I. M. Lif-shitz and, independently, Geoffrey Chester had raised the possibility of a condensation of zero-point vacancies or defects.

Kim and Chan reasoned that if they solidified 4He in Vycor, the incommensurate shapes of crystal lattice and small pore would enhance the number of vacancies and so increase the chances of seeing a supersolid component. According to that logic, one would expect the amount of supersolid behavior to decrease when the 4He was frozen in the larger pores of porous gold, and to be still less evident in bulk 4He. But that was not the case. Moreover, it is experimentally and theoretically far from clear that bulk 4He at low temperatures has enough vacancies (or dislocations) to support supersolid flow.

On the other hand, notes Beamish, the Vycor and Goodkind experiments were very sensitive to 3He contamination. (Kim and Chan plan to investigate whether the bulk-helium system behaves similarly.) Since dislocations can be pinned by very small impurity concentrations, the 3He may be providing a clue that dislocations are important after all.

The possibility of atomic exchange arises because solid 4He has an unusually large zero-point motion: The root-mean-square displacement of an atom at absolute zero is 30% of the crystal lattice spacing. Significant wavefunction overlap could lead to neighboring atoms swapping positions. If the exchange is frequent and extensive enough, decoupling could result. “That’s the most intriguing possibility of all,” says Leggett, “though I’d bet against it.”

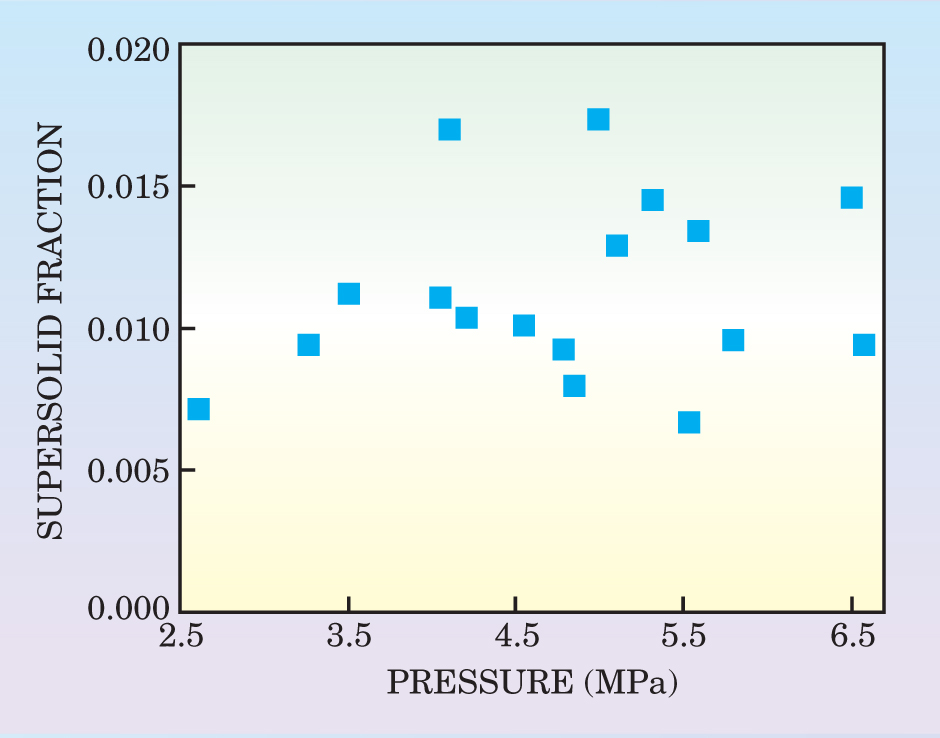

Intuitively, one might expect that the effects of vacancies, dislocations, and exchange would depend significantly on pressure. Thus, one of the mysteries of the bulk-helium experiments is that the low-temperature limit of the supersolid fraction exhibits no discernible dependence on pressure. Figure 3 presents the evidence. Kim and Chan are working to reduce the scatter in their current data. They hope that more uniform cooling of the 4He will do the trick.

No trend. The fraction of helium-4 that behaves as a supersolid in the low-temperature limit shows no evident dependence on pressure. That’s surprising if the supersolid behavior results from vacancies, dislocations, or atomic exchange in the 4He lattice.

(Courtesy of Eun-Seong Kim and Moses Chan.)

BEC or friction free?

Supersolid motion could be manifested as a metastable persistent flow or as a genuine equilibrium phenomenon sometimes called nonclassical rotational inertia. According to Leggett, the jury is out on whether the latter inevitably implies the existence of a BEC; the link between metastable flow and Bose–Einstein condensation is more tenuous. Instead of having the long-range correlations of a BEC, the system could simply have a small component of the 4He somehow snaking without friction through the rest of the possibly deformed lattice.

The 5 µm/s critical velocity below which decoupling saturates hints that the supersolid may have long-range order. If the supersolid 4He going around an annulus has such order, its speed will be an integral multiple of a characteristic speed determined by the atomic mass of 4He and the radius of the annulus. For Kim and Chan’s setup, the quantization speed is a bit over 3 µm/s. Thus, one possible explanation for the saturation is that the 4He is a BEC and when the annular speed increases beyond a few micrometers per second, vortices (that is, states with nonvanishing speed quantum number) kick in and reduce the observed decoupling. To test that interpretation, Kim and Chan plan to repeat their experiment, but with a torsional cell containing 4He in two concentric annuli. If the interpretation is correct, they should see different saturation speeds for the two annuli.

The nature and microscopic causes of what Kim and Chan have observed in bulk 4He remain unresolved. The explanations that seem most natural have their deficiencies, which is just fine with Hallock. “Anytime somebody sees something that challenges what we know,” he says with relish, “man, that’s what it’s all about!”

References

1. E.-S. Kim, M. H. W. Chan, Nature 427, 225 (2004).

2. E.-S. Kim, M. H. W. Chan, Science 305, 1941 (2004).

3. A. J. Leggett, Science 305, 1921 (2004).