Slow-growing pebbles lead to fast-growing Jupiters

DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.2968

The planets in our solar system started out some 4.5 billion years ago as dust and gas in a protoplanetary disk surrounding the infant Sun. Radioactive dating of meteorites and other rocks indicates that Earth grew to its present size over a period of some 100 million years. (See the article by Bernard Wood, Physics Today, December 2011, page 40

Ironically, the much larger solid cores of the gas-giant planets had to have formed much more quickly. Looking around the Milky Way at young star-forming regions, astronomers have found that gas disks surrounding young stars dissipate within the first 1 million to 10 million years. The cores of gas giants had to grow large enough—to 10 Earth masses—to be able to sweep up that nebular gas in time.

In the traditional picture of planet formation, dust in the protoplanetary disk clumps up to form pebbles that in turn collide and stick together to make rocks. The rocks then accrete to make boulders and so on to ever larger objects. But in planet-formation simulations, that mechanism works too slowly for the gas giants.

In 2012 Anders Johansen of Lund University in Sweden, together with his then graduate student Michiel Lambrechts (now at Nice Observatory in France), showed that the cores of gas giants could form much more efficiently if growing planetesimals fed on centimeter-sized pebbles rather than each other. 1 But that pebble accretion was perhaps too efficient. When Harold Levison and Katherine Kretke of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, included pebble accretion in their simulations, they ended up with hundreds of Earth-sized objects rather than a few gas giants, like the four in our solar system. 2

Now Levison, Kretke, and Martin Duncan of Queen’s University in Canada have tweaked the model by adding as a control knob the rate at which pebbles form out of dust in the protoplanetary disk. Their new simulations show that slowing down pebble formation can produce the hoped-for handful of gas-giant cores. 3

Meter barrier

A major stumbling block for planet- formation models is the so-called meter barrier. Electrostatic forces can make dust particles stick together. “That’s why we get things like dust bunnies underneath our beds,” Levison explains. For kilometer-sized objects, gravity can do the job. For sizes in between, neither force is strong enough to make things stick.

Even if objects could somehow grow to be bigger than pebbles, adds Levison, they face yet another fatal obstacle: aerodynamic drag from the gas in the disk. Dust can simply float around in the gas, and planet-sized objects feel the drag as a minor perturbation. However, for centimeter- to meter-sized objects, the situation is dire. The drag from the gas removes so much angular momentum from their orbits, they quickly spiral into the disk’s central star.

Johansen and Lambrechts built on earlier work showing that turbulence in the protoplanetary disk could concentrate a population of pebbles into clumps. Those clumps become gravitationally unstable and collapse directly into 100- to 1000-km-sized planetesimals and thus bypass the need to grow intermediate-sized rocks and boulders. 4 “You go from things the size of coffee cups to things the size of Pluto almost overnight,” says Levison.

Once the planetesimals are in place, they quickly accrete the pebbles that are left over, thanks to the aerodynamic drag that proved so problematic for traditional formation models. 5 “The gas drag is strong enough to cause particles approaching the planetesimal to spiral in,” says Duncan. The whole process might play out within a million years.

Too many planetesimals

When Johansen and Lambrechts proposed their pebble-accretion model, Levison and colleagues were at first skeptical, to say the least. “I saw this stuff and I hated it because I had this other model I was working on,” Levison recalls.

Johansen and Lambrechts focused on making single planets, but Levison and his colleagues saw there would be a problem if multiple planetesimals were allowed to grow simultaneously: The smaller planetesimals would grow slightly faster than larger ones. That meant large objects couldn’t grow at the expense of small objects. Indeed, in their global simulations starting from an initial population of planetesimals and pebbles Levison and Kretke showed that pebble accretion would produce hundreds of Earth-sized objects in the outer solar system.

Before writing off the new theory, Levison and Kretke wanted to make sure their analysis was complete. They figured that the key issue in their simulations was that the planetesimals accreted the pebbles and grew large before they had a chance to gravitationally interact with each other. If planetesimals grew more slowly, maybe they would accrete one another quickly enough to reduce the number of planets at the end.

So the researchers ran one more simulation, and instead of starting with a population of preformed pebbles, they allowed the pebbles to form slowly. “And then boom, that simulation worked,” says Levison. But not for the reason they originally thought.

With more simulation runs and a close examination of the results, Levison, Kretke, and Duncan found that tuning pebble formation to a slower rate didn’t lead to the planetesimals accreting each other. Rather, the larger planetesimals scattered the smaller ones to higher-inclination orbits. That meant the small objects spent most of their time in regions without pebbles. The large planetesimals were then able to efficiently accrete the pebbles in their vicinity and grow even larger.

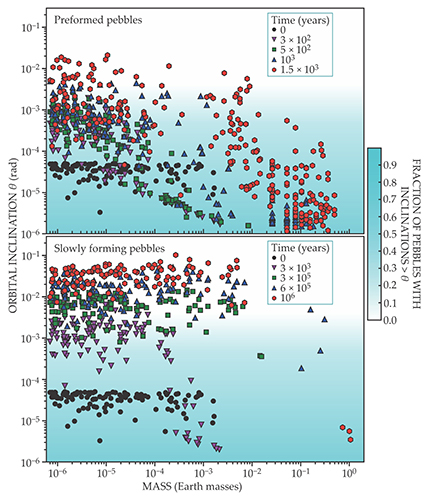

The figure shows the results of two simulation runs illustrating the effect. The two runs have identical parameters except that one starts out with a population of preformed pebbles (top) and the other allows the pebbles to gradually grow (bottom). The difference in the end results is stark: Starting the simulation with preformed pebbles leads to many nearly Earth-sized objects that stop growing within 2000 years; on the other hand, allowing slow pebble growth produces a handful of Earth-sized planetary cores within a million years.

Pebble-accretion simulations of planet formation reach drastically different results depending on whether the pebbles form slowly or quickly out of the protoplanetary disk of dust and gas. The blue gradient indicates the vertical distribution of pebbles as represented by the orbital inclination θ. The planetesimals are shown at various times within the simulations, as indicated by the shapes and colors of the symbols. When pebbles are present from the start of a simulation (top), many nearly Earth-sized objects rapidly grow together at low-inclination orbits. When the pebbles are allowed to grow slowly out of the dust (bottom), the largest few objects have enough time to gravitationally scatter smaller objects to higher-inclination orbits away from the pebbles and hog the pebbles for themselves. The end result is the formation of a few Earth-sized planetary cores that can further evolve into gas giants. (Adapted from ref.

Levison, Kretke, and Duncan tested one other constraint on planet-building models. In some simulations, they placed Pluto-sized planetesimals out at orbits between 20 AU and 30 AU and confirmed that those objects stayed in low-inclination orbits but did not grow; that finding is consistent with what is observed in the Kuiper belt.

Still early days

John Chambers of the Carnegie Institution of Washington says that the new results overcome some long-standing hurdles for planet-formation models. Nonetheless, he adds a note of caution: “Pebble accretion models are still in their infancy. The new work is definitely a substantial step forward, but it is not the last word on the subject.” For example, Chambers points out that having the growth rate of pebbles as a control knob is somewhat artificial.

Although Levison wouldn’t disagree, he explains that IR observations of protoplanetary disks around young stars show that dust in those disks lasts for millions of years. Those observations could justify the idea that pebbles slowly form out of the dust, even if the exact process is not understood.

In addition, planetesimals should, in principle, form alongside the pebbles instead of being present from the start. However, the group decided to add them at the beginning for simplicity. The simulations were already computationally expensive, with runs taking weeks to finish. “We don’t expect the qualitative results to be any different between the two ways,” Duncan says.

In the meantime, the group is moving forward with extending their model inward in the solar system—their initial simulations had an inner edge just inside the giant-planet region, again for reasons of computational cost. They’re checking to see if the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter survives planet formation through pebble accretion. And they are investigating how pebble accretion might apply to the formation of the terrestrial planets. Says Levison, “We’re moving around the solar system, trying to see where pebble accretion works and where it doesn’t.”

References

1. M. Lambrechts, A. Johansen, Astron. Astrophys. 544, A32 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201219127

2. K. A. Kretke, H. F. Levison, Astron. J. 148, 109 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-6256/148/6/109

3. H. F. Levison, K. A. Kretke, M. J. Duncan, Nature 524, 322 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14675

4. A. Youdin, J. Goodman, Astrophys. J. 620, 459 (2005); https://doi.org/10.1086/426895

A. Johansen et al., Nature 448, 1022 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature060865. C. W. Ormel, H. H. Klahr, Astron. Astrophys. 520, A43 (2010).https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014903