Secrets of ancient aquifers

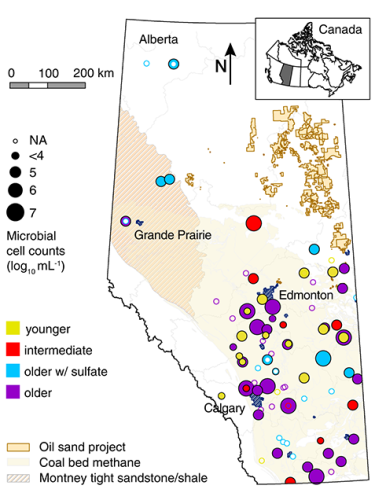

Groundwater wells scattered throughout Alberta, Canada, were used to study subsurface microbes. Colors indicate the groundwater age at each well: Yellow denotes several years to decades, red is several decades to a few hundred years, and blue and purple are several hundred years to more than 40 000 years. Circle size represents the average microbial cell numbers in the groundwater samples, ranging from 104 cells (smallest full circle) to 107 cells (largest circle) per milliliter.

S. E. Ruff et al., Nat Commun. 14, 3194 (2023)

About 50% of people around the world rely on groundwater for drinking. It usually contains between 104 and 105 microbial cells per milliliter, and those microbial communities are shaped by and interact with the environment in which they develop. The exact distribution of organisms and the chemistry and physics of the water, including pH levels and temperature, vary between different aquifers.

The effect of those environmental differences on the microbiomes is what Emil Ruff at the University of Chicago–affiliated Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and colleagues were hoping to study. They turned to an expansive system of 95 sampling wells in Alberta, Canada, that have been monitored for decades. Those wells, mapped on the figure, range from 5 m to 231 m deep and tap underground aquifers with water that has been out of contact with the atmosphere from between several years to more than 10 000 years. That large sample of spatial and temporal data has previously been used for biogeochemical studies, but until Ruff and colleagues’ work, it had not been used in microbial studies (see the article by Mary Anderson, Physics Today, May 2007, page 42

Previously, scientists had assumed that as they sampled deeper layers of Earth, and thus older water sources, the number of organisms would decrease. Because oxygen nearly always needs light to be produced photosynthetically in plants and microbes, groundwater ecosystems, especially older ones, were thought to be oxygen depleted. When the undergraduates in Ruff’s lab were counting cells, however, they found both a higher number of organisms and oxygen, two unexpected findings that changed the focus of the work.

Collecting groundwater samples from monitoring wells is tricky business. Water is pumped via sterilized tubing and sampled on-site to reduce the chance of contamination. Muhe Diao, with the University of Calgary, shows the marker put up to keep people from tampering with the experiment.

Muhe Diao

The researchers took a year to ensure that they hadn’t accidentally introduced oxygen into their samples through contamination with air. New samples were collected, and existing samples were reanalyzed using mass spectrometry and gas chromatography. But the results were robust. A literature search revealed that they weren’t the only ones to have discovered oxygen anomalies in groundwater. Going back decades, other researchers had commented on finding oxygen where they thought there shouldn’t be any. Ruff’s team of interdisciplinary scientists made the extra leap and proposed a compelling explanation: The oxygen could be produced by microbes. The researchers found not only oxygen but also microbes whose genomes contained the necessary genes and metabolic pathways to produce oxygen in the absence of light.

Biological sources that can produce oxygen without light are not new to biologists, who have studied them for the last three decades in the lab. Such sources, however, hadn’t been found to be widespread in groundwater. But the discovery of those genes, the presence of oxygen, and the unexpected amount of cellular life in the deep, old wells challenge conventionally held wisdom on subsurface cell abundances and activity.

The team is now looking into better understanding how the naturally occurring oxygen may be cleaning the groundwater of greenhouse gases, such as methane, and toxins, such as sulfide. That insight could help engineers design a more biologically driven method of ensuring that everyone has access to clean drinking water. (S. E. Ruff et al., Nat. Commun. 14, 3194, 2023