Science survives budget battles

DOI: 10.1063/1.2718748

For most of January, science advocates in Washington, DC, were in a state of barely controlled panic as it became increasingly apparent that the much-ballyhooed science funding increases contained in the Bush administration’s fiscal year 2007 budget proposal weren’t going to happen. The FY 2007 budget, caught between the inaction of the Republican-controlled 109th Congress and the “it’s not our budget” view of the 110th Democratic Congress, was dead.

Instead, the Democratic leadership was promising that the government would live out most of 2007 at 2006 funding levels through a continuing resolution. With the FY 2007 budget proposal shelved, Congress could focus its attention on the administration’s FY 2008 budget proposal, which was released on 5 February. For science organizations—both inside and outside of government—the continuing resolution solution to the budget impasse was, in the words of American Physical Society (APS) public affairs director Michael Lubell, “a disaster.”

After years of advocating for more federal science money for basic research, particularly at the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and at NSF, the science community and private industry convinced the administration to significantly increase nondefense science funding. A year ago President Bush released the American Competitiveness Initiative, which called for doubling funding for research over 10 years for NSF, the Office of Science, and NIST.

“Spectacular,” “historic,” and “extraordinary” were some of the superlatives used by officials at DOE, NSF, and nongovernmental science organizations to describe the money proposed by Bush in the FY 2007 budget (see Physics Today, March 2006, page 25

If the continuing resolution truly kept FY 2006 funding levels in place until the FY 2008 budget took effect, which would be 1 October 2007 at the earliest, Lubell’s fear of a disaster would be well founded. DOE officials released a six-page “impacts” document saying the $1.4 billion Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, would be delayed a year in ramping up to full power; the National Synchrotron Light Source II project at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York would lay off 50 people; the US share of ITER, the international prototype fusion energy reactor, would receive only 50% of obligated funding, which would trigger international partnership problems; and the entire staff at Fermilab, near Chicago, would be furloughed for a month.

NSF Director Arden Bement sent a “Dear Colleagues” letter to many in the scientific community on 12 January. In it, he said, “NSF is being funded at the FY 2006 level, roughly $400 million below the Administration’s FY 2007 request,” and if that remained the case, “NSF may be unable to fund a number of activities planned for the fiscal year.” Those activities included a solicitation for a new arctic research vessel, the petascale acquisition program for the office of cyberinfrastructure, and 40 planned graduate research fellowships.

Push for funding

Efforts by science supporters in Congress and the administration, as well as massive lobbying and letter-writing campaigns from the science community and others outside government, focused on getting Representative David Obey (D-WI), chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, and Senator Robert Byrd (D-WV), chairman of the Senate Committee on Appropriations, to “open up” the continuing resolution so money could be added for science.

“They indicated in December that they were loath to make any adjustments, but the door was left open a crack,” APS’s Lubell said. “We made the argument that you could put off building a new courthouse or a highway for a year without a lot of impact, but if you shut down science facilities and reduced grants, then people were going to go elsewhere and you would lose your workforce.”

Along with e-mail campaigns by APS, the Association of American Universities, and a host of other nongovernmental organizations, a campaign to increase science funding was also under way inside Congress. Representative Rush Holt (D-NJ), a physicist, discussed the need for increased science funding with Obey and other members of Congress who have national laboratories and high-tech industries in their districts. Similar efforts were under way in the Senate. In November, 23 senators signed a letter to Senate leaders supporting more funding for NSF, and 45 senators signed a letter calling for more money for DOE’s Office of Science.

Making the list

On 19 January a staff member for an influential congressman told Lubell that science had gone up on the priority list and was being considered as important as veterans issues and highway funding.

“That was the first inkling we had that we’d broken through,” Lubell said.

Ten days later, on 29 January, Obey filed a $463.3 billion continuing resolution that he wrote with Byrd. Much of the science funding proposed in the administration’s FY 2007 budget was in the resolution. In his summary of the continuing resolution, Obey noted that the appropriations committee cut more than 60 programs to below FY 2006 funding levels and rescinded other funding to provide about $10 billion that could be used for “crucial investments,” including science. The cuts included $3 billion from military base relocation funding, $700 million in foreign aid, and $700 million that had been slated for Iraq reconstruction. “I don’t expect people to love this proposal, I don’t love this proposal, and we probably have made some wrong choices,” Obey said.

New funding went to veterans, with a $3.6 billion increase above the FY 2006 funding of $32.3 billion. And as the congressional staffer indicated to Lubell, the Federal Highway Administration received $3.5 billion over its FY 2006 funding.

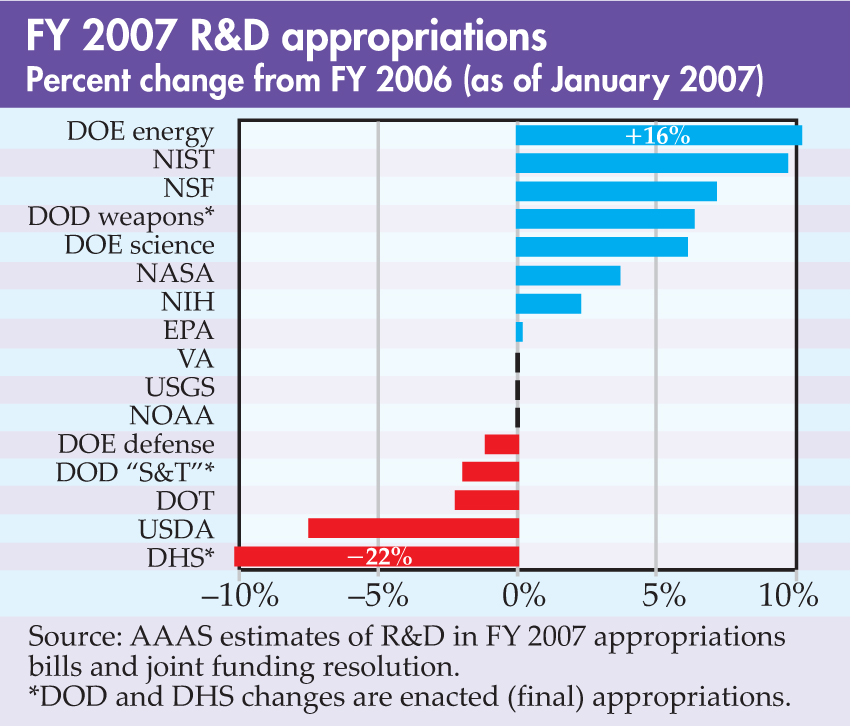

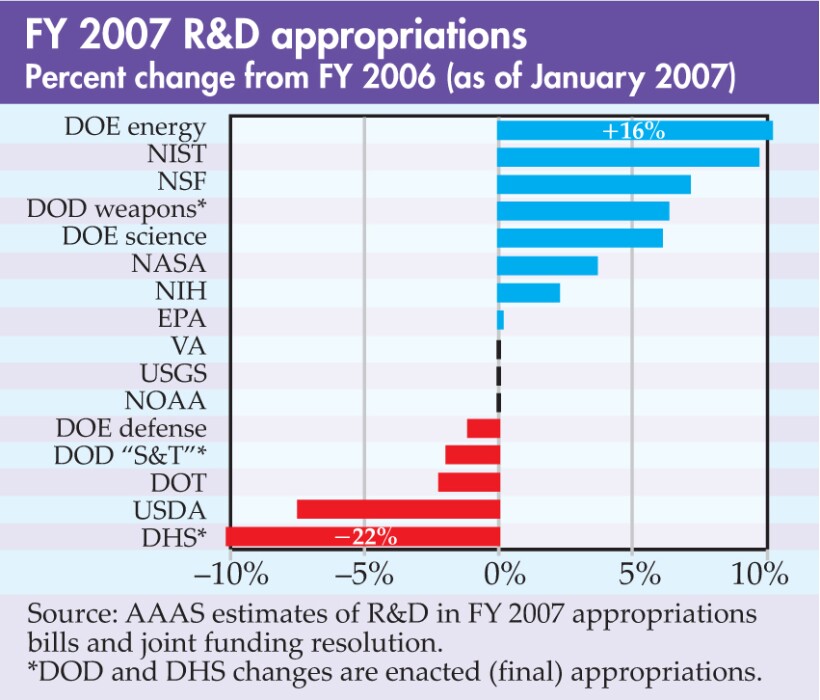

But what surprised the science community was that the continuing resolution contained significant increases for nearly all the key science programs slated for increases in the administration’s FY 2007 budget proposal. According to an analysis by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the resolution, if passed unchanged by the Senate in mid-February, sets funding for key science programs as follows:

-

▸ NSF would receive the full FY 2007 increase of 7.7%, or $334 million, for its Research and Related Activities account. Bringing that account to $4.7 billion would reverse several years of decreased funding for most of the NSF research directorates. Overall, NSF R&D would increase 7% to $4.5 billion. Major research and equipment would remain flat, as would education and human resources.

-

▸ DOE’s Office of Science would receive a 6% boost to $3.5 billion, less than the 14% in the FY 2007 budget proposal, but a boost nonetheless. The resolution also allows the science office to redirect $126 million in 2006 funds that were earmarked for other projects. In addition to providing $160 million for ITER, the increase should allow the SNS and the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider to operate, and provide enough money for Brookhaven’s new light-source project to proceed. The 12-GeV upgrade to the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Virginia should also receive funding.

-

▸ NIST would receive an increase of $50 million over current funding, a 9.6% increase instead of the 20% proposed by the administration. The resolution also keeps the Advanced Technology Program going despite administration efforts to zero out the funding.

-

▸ NASA would see a $545 million reduction in its budget from the FY 2007 request. The continuing resolution directs reductions of $667 million in the human spaceflight program, while at the same time increasing the space agency’s R&D program by 3.6% to $11.7 billion. The shifting of money away from human spaceflight prompted NASAadministrator Michael Griffin to say that, if left unchanged by the Senate, the continuing resolution would jeopardize the development of the manned spacecraft intended to replace the space shuttle and would have “serious effects on … people, projects, and programs.

Although there was widespread relief in the science community about the increased science funding, the administration released a policy statement criticizing many of the specifics of the continuing resolution, such as the $3 billion taken from military base closings. The statement also called for more money for science, saying Congress should have added another $450 million to basic research funding.

With the continuing resolution crisis apparently averted and all sides in Washington seemingly supporting increased science funding, can Lubell and other science advocates declare victory and relax?

As the administration pushes for the elimination of the federal deficit—predicted to be about $340 billion for FY 2007—and as Democrats in Congress adopt a “pay as you go” approach to funding, the competition for money will only become more intense. And because, as Lubell said, “science isn’t a spending program, it’s an investment program,” it is more difficult to sell to members of Congress who like to bring tangible projects back to their constituents.

The congressional continuing resolution increases funding over FY 2006 levels for NSF, NIST, and DOE science in response to the American Competitiveness Initiative. Energy R&D at DOE gets the biggest boost.

AAAS