Science diplomacy enlisted to span US divide with developing world

DOI: 10.1063/1.3529398

The timing was “impeccable,” says Charles Ferguson, president of the Federation of American Scientists. He had just briefed an interagency gathering of federal officials on 29 October about an FAS plan to bring US and Yemeni scientists together to try to solve Yemen’s critical water shortage. Just hours later came the news that two expertly crafted bombs planted in packages originating in Yemen had been located aboard cargo planes that were headed to the US.

Ferguson believes that the foiled terrorist incident might improve chances that the FAS will receive the federal support it needs to send scientists to Yemen to attend conferences and conduct field research on water with their Yemeni counterparts. He and an Arabic-speaking FAS staffer had already held preliminary talks with Yemenis in Sana’a, the capital city, where the water supply is projected to dry up within 10 years. Social scientists must help, Ferguson notes, because water isn’t just a technical problem. By some estimates, 40% of Yemen’s water is used to irrigate khat, a plant that is cultivated for the amphetamine-like compounds found in its leaves. Four-fifths of Yemeni men and 40% of women there chew the leaves.

The FAS is not the first US scientific nongovernmental organization to get involved in science diplomacy to help improve relations and reduce tensions with nations that for various reasons aren’t so friendly with the US. Efforts have been under way for years at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), and the less-known nonprofit CRDF Global. The efforts have been bolstered by the Obama administration’s initiative to extend an olive branch to the Muslim world through science and technology collaborations. In October the administration broadened its S&T outreach to the entire developing world.

A variety of approaches

Science diplomacy at its most dramatic has been on display in the visits by delegations of prominent scientists to countries that are officially ostracized by the US—whether for sponsoring terrorism, violating human rights, or pursuing nuclear weapons programs. Arranging those trips has become a specialty of the AAAS, with financing provided by the likes of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Richard Lounsbery Foundation (see Physics Today, February 2010, page 25

A more nuts-and-bolts, behind-the-scenes type of science diplomacy is the business of CRDF Global. The nonprofit, formerly the Civilian Research and Development Foundation, was established in 1995 by NSF, with a nudge from Congress. Its mission was tightly focused: helping unemployed weapons scientists in the former Soviet states find alternate work and thus reduce the risk that they might try to sell their skills to nations eager to develop their own weapons capability. Since then, CRDF says it has provided financial and other support to more than 6600 Eurasian scientists and engineers, using peer-reviewed, competitively awarded grants. Each of those projects paired the former Soviets in a collaboration with US scientists.

An expanding role

Other types of collaborations flowed from that work. Under Soviet rule, all research was done at government institutes; universities were only for teaching. At the request of the new Russian government, CRDF reorganized and incorporated basic research into three Russian universities so they resembled US research universities. Russian officials were pleased enough with the results that they replicated the transformation at 27 other universities, says former National Academy of Engineering (NAE) president William Wulf, who is a CRDF board member. That transformation was then performed for Ukrainian universities and eventually at universities in four other republics. The foundation also set up experimental support centers at 21 locations in eight former Soviet states to provide researchers with access to shared experimental equipment.

Over the past six years, CRDF expanded into other regions, first to the Baltic nations and Eastern Europe and most recently to the Middle East and North Africa. Today it operates programs in more than 30 countries, says Cathleen Campbell, its president. Throughout its existence, CRDF has had to seek funding for each of its programs from NSF, the US Agency for International Development, and other sponsors. Although a federal endowment was part of the legislation that created CRDF, Congress never got around to making an appropriation, explains Eric Novotny, CRDF senior vice president.

Obama’s Cairo pledge

So it was a milestone of sorts when in June, Maria Otero, the undersecretary of state for democracy and global affairs, announced that CRDF would receive its first congressional earmark. The five-year, $5 million grant, channeled through the State Department, will launch at CRDF a regional program called Global Innovation through Science and Technology. A $1.5 million chunk of GIST will be to create a digital science library for the Maghreb — Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania—that replicates the virtual science libraries that have been operating in Iraq and Pakistan for several years, providing access to scientific literature for thousands of Iraqi scientists (see the related story on

As with the FAS foray into Yemen, CRDF’s timing turned out to be perfect on GIST. In a June 2009 speech at Cairo University, President Obama proposed that the US form collaborations in S&T with Arab and other Muslim-majority countries. “Here we’d been talking all along about a number of the components, and it tied in beautifully with the president’s address,” CRDF’s Campbell says. But even though a second $5 million earmark is anticipated for GIST, the sum, she says, is “minimal” for an initiative of that scope.

Roughly half of GIST will support putting together and conducting a major S&T innovation conference in Morocco in June 2011. “The idea is that we will engage in consultations with leaders throughout the Muslim world to establish a financing mechanism to help commercialize technology,” says Lawrence Gumbiner, deputy assistant secretary of state for science, space, and health. The goal is to have a solid proposal for a fund and sufficient contributions to support some pilot commercialization projects in areas of regional or global need.

A third component of GIST is a CRDF staple: redirecting the work of former weapons scientists or those with skills of “dual-use” concern. Libya, for example, operated chemical and biological weapons programs in the past. “We want to pick some countries and use them as a model of how, through training and workshops, you can equip them to transfer from a weapons- or security-based community to a civilian model,” Gumbiner says.

The commonality of science

American scientists report that US science is held in high regard even in countries whose leaders and populace are hostile to every other aspect of American culture and policy. Their observations are supported by polling data. One frequently cited 2004 survey, by Zogby International, found that only 11% of Moroccans had a favorable view of the US overall, but 90% had a positive view of US S&T. In Jordan, the numbers were 15% and 83%, respectively. Students at Iran’s Sharif University of Technology were so enthralled with a guest lecture by visiting US Nobel physics laureate Joseph Taylor in 2007 that they erected a statue of him on the campus.

“Scientists and engineers share a set of values which is pretty much independent of culture,” says Wulf, who during his 11 years at the NAE got to know Iranian scientists, engineers, and even former president Mohammad Khatami on his visits to Tehran. “We are big believers that scientists speak a universal language, create collaborations, and build bridges at times when official relations are cooler,” agrees Gumbiner. “Everything that we’ve seen coming out of [the visits] and what we’ve heard back from AAAS, NAS, and others has been positive.”

Wulf says that nongovernmental organizations are key to successful science diplomacy. “Anything that smacks of the US government trying to implement something in another country is [seen as] sort of manipulative and suspect, even if it’s done with the best of intentions,” he says. And collaborations must be beneficial to both sides. “It can’t just be Americans telling them how to do this,” Ferguson says. “It’s not a Peace Corps model.”

Centers, dollars, and envoys

Obama’s Cairo initiative contained other elements. As much as half of the $100 million “global engagement fund” that the president has requested in his budget for the current fiscal year will be used for S&T collaborations with the developing world. The bulk of that will be used to establish “centers of excellence” abroad in scientific cooperation in four priority areas—health, energy, water, and climate change. Although the locations aren’t official, the climate center will likely be in Southeast Asia and the Middle East will likely host the center on water. The centers will consist of “interconnections among institutions engaged in first-class research,” rather than bricks and mortar, says Gumbiner.

During her travels in October, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton signed new S&T agreements with Malaysia and Turkey, adding to the dozens of such bilateral accords that are in place. But there are only two S&T agreements that come with funding attached; both are with Muslim states. The US has tripled its contribution to the Egyptian S&T agreement in the past two years, to $4.5 million; Egypt matches that amount. The US has provided $9.3 million to fund a fourth round of collaborative S&T grants with Pakistani scientists. Pakistan has kicked in another $4.5 million.

The Cairo initiative also led to the appointment of prominent US scientists to serve as science envoys and travel abroad in search of potential topics for collaboration. In October three more envoys were named: former NSF director Rita Colwell, Lehigh University president Alice Gast, and Purdue University agronomist Gebisa Ejeta. They will be visiting their designated developing nations—including some that do not have Muslim majorities—early in the new year. The first three envoys, former National Institutes of Health director Elias Zerhouni, Caltech chemistry professor Ahmed Zewail, and former NAS president Bruce Alberts, were named in November 2009 (see Physics Today, January 2010, page 23

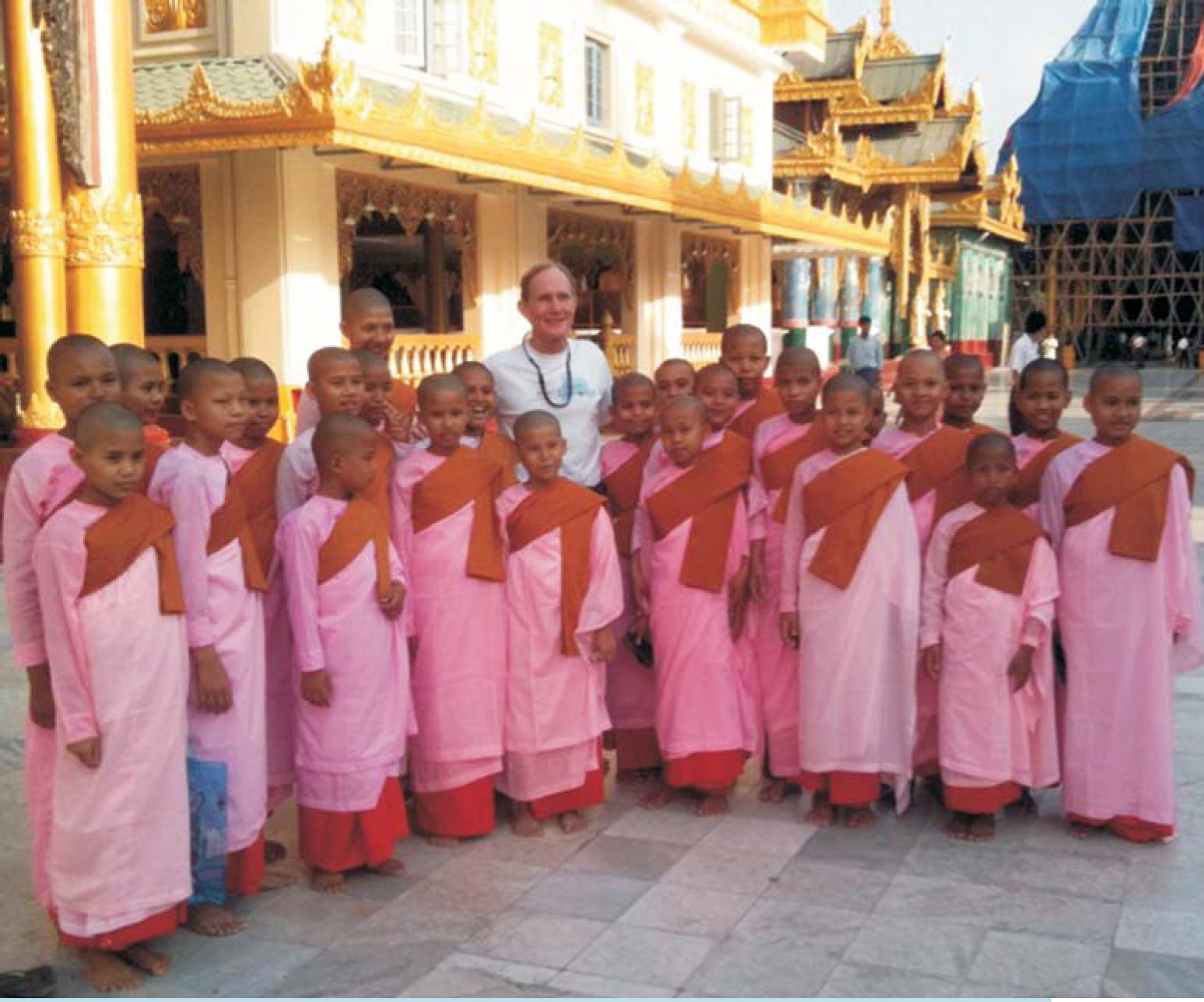

Nobel laureate chemist Peter Agre poses with Buddhist nuns in Yangon, Myanmar. In May Agre led a delegation to the Southeast Asian nation that sought to foster bilateral scientific ties. The US has long imposed economic sanctions against Myanmar’s ruling junta for its ongoing human rights violations.

VAUGHAN TUREKIAN, AAAS

More about the authors

David Kramer, dkramer@aip.org