Radar reveals Mercury’s molten core

DOI: 10.1063/1.2761789

Mercury’s rotation rate oscillates with a greater amplitude than it would if the planet’s core were entirely solid. That is the conclusion of a team of researchers, comprising Jean-Luc Margot from Cornell University; Stan Peale from the University of California, Santa Barbara; Raymond Jurgens and Martin Slade from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California; and Igor Holin from the Space Research Institute in Moscow. They base their finding on recent radar measurements and the decades-old data from the Mariner 10 probe. 1

Mercury’s structure is similar to Earth’s: It contains a dense metallic core surrounded by a silicate mantle and a rocky crust. But seismic measurements provide additional information about Earth that’s harder to come by in the case of other planets. It’s known that the outer part of Earth’s core is molten, due mostly to the heat produced by radioactive decay, whereas the inner core is kept solid under the gravitational pressure of the outer layers. Although Earth’s mantle behaves like a fluid over the long time scales of continental drift, for faster processes the mantle is best characterized as a solid.

Earth’s magnetic field isn’t produced by the solid inner core, whose temperature is higher than the Curie temperature of iron and therefore cannot sustain a permanent magnetization. Instead, the convection of the molten outer core produces a self-sustaining planetary dynamo: The flow of the liquid metal through the magnetic field generates an electric current, which in turn enhances the field. (See Physics Today, February 2006, page 13

In 1974 Mariner 10 detected a weak Mercurian magnetic field. That came as a surprise. Because Mercury is less than 6% as massive as Earth, it has a large surface-to-volume ratio. Planetary scientists expected that it would lose heat rapidly enough that the core would have solidified completely. A fully solid core makes a dynamo impossible but doesn’t necessarily preclude a magnetic field. Mars and the Moon both have magnetic fields that emanate from their crusts, magnetized long ago by dynamos that have since ceased their activity. But the Martian and lunar magnetic fields are patchy and uneven, since some parts of the crusts have retained more of their magnetization than others. Mercury’s field has a large dipole component, which led researchers to wonder: Might the core be liquid after all?

Torque from the Sun

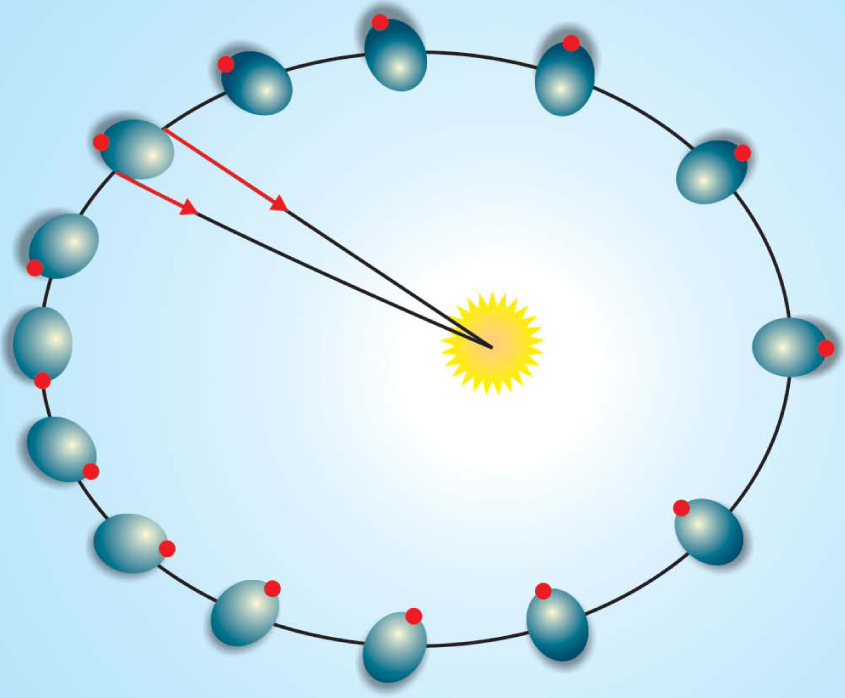

In 1976 Peale suggested a way to determine the state of Mercury’s core. 2 As Mercury orbits the Sun, it experiences a small torque due to its slight asymmetry in the plane of its orbit, as shown in figure 1. The resulting oscillation in its rotation rate is known as a forced libration. If Mercury’s core were entirely solid, it would be rigidly attached to the mantle, and the entire planet would experience the forced libration. But a liquid layer in the core would mean that only the mantle and crust would respond to the torque, so the libration amplitude would be larger.

Figure 1. As Mercury rotates about its axis three times for every two trips around the Sun, the gravitational forces (red arrows) on parts of the planet create an overall torque. The resulting oscillation in the spin rate, called a forced libration, provides information about Mercury’s interior. Here, the eccentricity of the orbit and the planetary profile are exaggerated for effect, and the red dots are included to guide the eye.

Applying Peale’s method entails not only measuring the amplitude of the forced libration but also calculating just how big it should be in the solid-core and liquid-core cases. The magnitude of the solar torque is proportional to the difference between the moments of inertia about the two axes perpendicular to the spin axis. That quantity is known from the Mariner 10 measurements of Mercury’s gravity, but with an uncertainty of 50%.

The effect that the torque has on the spin rate is determined by C, the moment of inertia of Mercury about its spin axis, or C m, the moment of inertia of the outer layers alone, depending on whether the core is rigidly attached to the mantle. Both of those quantities can be estimated based on models of the interior of the planet. For a homogeneous sphere of mass M and radius R, C/MR 2 = 2/5. Since Mercury’s mass is concentrated at its core, it has a smaller value of C/MR 2, between 0.325 and 0.380. Mercury’s large average density suggests that the core makes up most of the planet’s volume, so C m/C is relatively small (less than 0.5).

There’s an additional constraint on the three principal moments of inertia if Mercury is in a so-called Cassini state, a product of tidal evolution. The Sun creates a tidal bulge in Mercury’s crust, similar to but smaller than the tides in Earth’s oceans, and distinct from the asymmetry shown in figure 1. Over time, that ever-moving bulge has drawn Mercury into a state in which its orbital and rotational periods are commensurate (in a 3:2 ratio), its spin axis and orbital plane precess at the same rate (with a period of 250 000 years), and the tilt of the spin axis satisfies a particular relation with the moments of inertia.

Radar speckles

Peale initially thought that the forced libration could not be measured accurately enough without landing sophisticated equipment on the surface of Mercury. But in 2001 Margot realized that there might be an easier way, using an Earth-based radar technique discussed by Holin 3 and Paul Green. 4 A coherent beam of light bounced off a distant rough surface comes back speckled, with the size of the speckles depending on the wavelength of the light, the distance to the surface, and the roughness of the surface. Shining a laser pointer at a wall produces small speckles; bouncing a radar beam off Mercury produces larger ones, on the order of 1 km. Like the spots of light reflected from a spinning mirror ball, the speckle patterns from the rotating planet sweep across Earth’s surface. By timing the speckles’ trip from one terrestrial receiver to another, Margot and his colleagues accurately measured Mercury’s instantaneous spin rate.

For the two receivers (in California and West Virginia) to see the same speckles, the line between them must be nearly parallel to the speckles’ trajectory. Because the tilt of Earth’s axis constantly changes the orientation of that line, there’s only a 20-second window each day during which proper alignment is achieved. The limited availability of the receiving telescopes, along with hardware failures at the two locations, meant that the researchers needed more than four years to accumulate 21 usable measurements of Mercury’s spin rate.

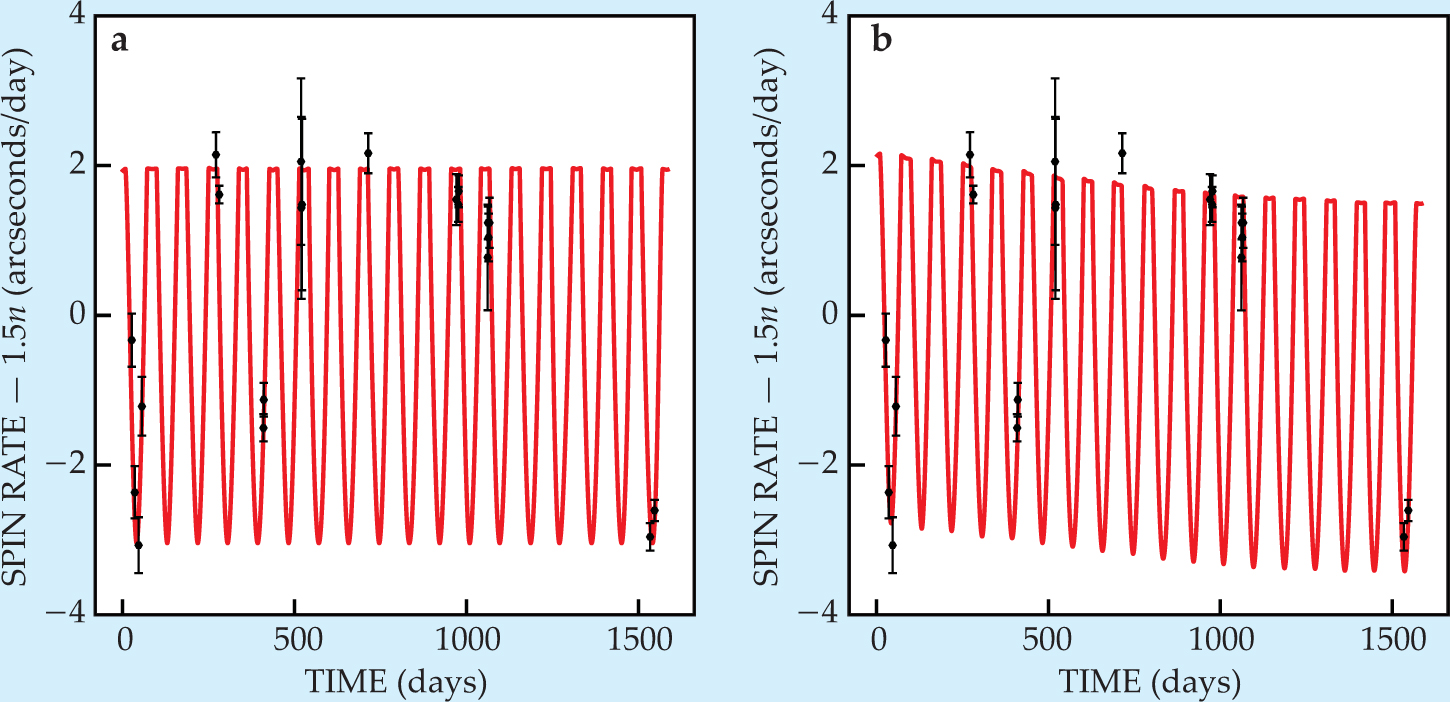

Those data points are shown in figure 2, with two possible fits. The first (figure

Figure 2. Radar measurements (black) of Mercury’s spin rate with respect to its average spin rate of 1.5 times its mean orbital frequency n. The two fits (red) account for (a) the forced libration only and (b) the forced libration and an additional free libration with a period of 12 years. In either case, the amplitude of the forced libration suggests that Mercury’s core is at least partially molten and that the solar torque affects only the solid outer layers of the planet. If Mercury were entirely solid, the forced libration would be considerably smaller.

(Adapted from ref. 1.)

The researchers performed Monte Carlo simulations to determine the effect of the uncertainties in the forced libration amplitude, the Mariner 10 measurement of Mercury’s asymmetry, and C/MR 2. As they considered different values for each of the three parameters, they found in the large majority of cases that the solar torque appeared to be acting on a moment of inertia considerably smaller than C. Only 5–10% of the trials indicated that the whole planet responded to the torque, so they concluded with 90–95% confidence that Mercury’s core has a molten layer.

Heart of brimstone?

Since Mercury is so small, and since it cools off so quickly, how can its core be liquid? One possibility is that the melting point of the core is lower than previously thought. That could happen if the core is rich in sulfur; just as salt water freezes at a lower temperature than fresh water, the melting point of an iron–sulfur mixture is lower than that of iron alone. But the material present at the time and place of Mercury’s formation should not have contained much sulfur. If Mercury’s core does contain sulfur, it’s likely that the planet was formed from pieces of material in the solar nebula drawn in from farther afield than previously thought.

Mercury is an extreme planet in many ways. It’s the closest to the Sun, it’s the smallest of the planets in our solar system, and its core is, proportionally, the largest. For those reasons, any new information about Mercury’s formation and interior properties will be particularly helpful for understanding planets under a wider range of conditions.

Instant messenger

Future work for Margot and his colleagues includes better characterization and understanding of the possible free libration. But the most anticipated development will come from the MESSENGER spacecraft. MESSENGER’s trajectory will provide better data on Mercury’s gravity field, and thus a more precise measure of the asymmetry that underlies the solar torque. The first flyby, next January, will reduce the uncertainty considerably; once the craft starts to orbit Mercury in March 2011, it will allow a measurement of still greater precision. By then, the 90–95% confidence in Mercury’s molten core could be improved to a virtual certainty.

References

1. J. L. Margot, S. J. Peale, R. F. Jurgens, M. A. Slade, I. V. Holin, Science 316, 710 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1140514

2. S. J. Peale, Nature 262, 765 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1038/262765a0

3. I. V. Holin, Radiophys. Quantum Electron. 31, 371 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01043597

4. P. E. Green, in Radar Astronomy, J. V. Evans, T. Hagfors, eds., McGraw-Hill, New York (1968), p. 1.

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org