Questions and answers with Silvan Schweber

DOI: 10.1063/PT.4.2432

By Jermey N. A. Matthews

|

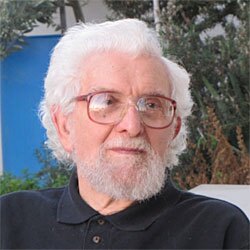

Silvan (Sam) Schweber is known equally for his achievements as a theoretical physicist and as a historian of science. He has written extensively in both fields.

Born in France, Schweber migrated to the US in 1942 and subsequently completed bachelors’ degrees in chemistry and physics at the City College of New York, a master’s degree in physics at the University of Pennsylvania, and a PhD in physics at Princeton University. He now serves as professor of physics, emeritus and Richard Koret Professor in the History of Ideas at Brandeis University, and he is a faculty associate in the department of the history of science at Harvard University.

Early in his career, Schweber wrote such seminal physics tomes as volume I of Mesons and Fields (Row Peterson, 1955), which he coauthored with Hans Bethe and Frederic de Hoffman, and An Introduction to Relativistic Quantum Field Theory (Harper and Row, 1961). As a historian, he has written several books, including QED and the Men Who Made It: Dyson, Feynman, Schwinger, and Tomonaga (Princeton University Press, 1994); In the Shadow of the Bomb: Bethe, Oppenheimer, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist (Princeton University Press, 2000); and Einstein and Oppenheimer: The Meaning of Genius (Harvard University Press, 2008). He also cofounded and was inaugural director for MIT’s Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology.

In 2011 the American Physical Society awarded Schweber the Abraham Pais Prize for History of Physics. In 2012 he completed and released the authorized biography, Nuclear Forces: The Making of Physicist Hans Bethe

PT: What motivated you to write this book?

SCHWEBER: In 1990 Bethe asked me to write his biography. I had been a postdoctoral fellow with him from 1952 to 1954 and had coauthored Mesons and Fields with him and Fred de Hoffman in 1955. [Bethe] wrote a preface to An Introduction to Relativistic Quantum Field Theory. In the mid 1980s he had noted that I had become a historian of science and was working on the post-World War II developments in theoretical physics.

PT: From your personal interactions with Bethe, what characteristics stood out to you?

SCHWEBER: To inform myself of his life we had extensive meetings in which he narrated his life. The first thing that struck me was his amazing memory and its accuracy. The second was his integrity: If he didn’t recall something, he would say, ‘I don’t remember.’ The third was the meticulousness with which he credited the work and the help of others.

PT: In this book, you focus only on Bethe’s early years, up to 1939. Do you have plans for an additional volume, and if so, can you give our readers a preview?

SCHWEBER: When Bethe asked me to write his biography, he indicated that he would like it to be an intellectual biography that would focus principally on his professional life and his scientific research. After he recalled his growing up, in particular his relation to his father and mother, I went to talk to people who had been students of his father. This introduced me to the remarkable Jewish community of Frankfurt, which in turn gave me an insight into the world his (future) wife, Rose Ewald, grew up in.

It then became a challenge to integrate life, work, and love. And this meant narrating his interactions with [Arnold] Sommerfeld, with [Enrico] Fermi, with Hilde Levi, with [Niels] Bohr, with Rose, [and with people in] the Cornell physics department. Since the world changed dramatically with World War II and Bethe’s world changed with it, the story of Bethe until 1940 had a certain coherence. I am working on a book that will narrate—episodically—the rest of his life. An initial account of my plans is to be found in an article I have recently submitted to Physics in Perspective.

PT: If you had to choose between nature and nurture, which one would you say was the definitive force that shaped Bethe?

SCHWEBER: Nature was responsible for making Bethe off-scale by endowing him with the possibility of the development of an amazing memory and amazing mathematical skills—the same way that nature is responsible for the possibility of Maurizio Pollini becoming an off-scale pianist, or Pablo Picasso becoming an off-scale painter. Nurture is responsible for those potentialities being realized.

PT: What books are you reading now?

SCHWEBER: Alexander Atland and Ben Simons’s Condensed Matter Field Theory (2nd edition, Cambridge University Press, 2010); Maciej Lewenstein, Anna Sanpera, and Veronica Ahufinger’s Ultracold Atoms in Optical Lattices (Oxford University Press, 2012); David Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity (reprint, Penguin Books, 2012); Christopher Fuchs’s Coming of Age With Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, 2011); and Italo Calvino’s The Uses of Literature (Harcourt Brace, 1986).