Precision spectroscopy that spans the mid-IR

Molecules run the gamut from floppy to stiff: The frequencies of their normal modes of vibration extend from less than 10 THz to more than 100 THz. That frequency range falls in the mid-IR, with wavelengths of 3–30 µm. In vibrational spectroscopists’ preferred unit of inverse centimeters, it’s 333–3333 cm−1. Regardless of how the range is expressed, many spectroscopic applications need to probe as much of it as possible at once.

The traditional way to achieve that aim is with a Fourier-transform IR spectrometer: From an incoherent broadband mid-IR source, a Michelson interferometer with moving mirrors selects an ever-changing combination of frequencies to be passed through the sample, and a computer converts the resulting interferogram into a spectrum. But that technique is too slow to get any real-time information about a sample, and its coarse resolution (on the order of 4 cm−1) is inadequate for many purposes.

Several areas of spectroscopy have seen dramatic improvements in resolution from the use of frequency combs: trains of equally spaced ultrashort pulses or, equivalently, superpositions of equally spaced frequency components (see Physics Today, December 2005, page 19

Now Abijith Kowligy and a team led by Scott Diddams

After the mid-IR frequency comb had passed through the sample, Kowligy, Diddams, and colleagues superposed it with a telecom-wavelength near-IR comb with slightly different tooth spacing, then passed the combination through a nonlinear optical crystal. The crystal adds the energies of the input waves together to generate a sum-frequency comb at a new, slightly higher frequency in the easily detected near-IR. The sum-frequency comb contains all the same spectral information as the mid-IR comb did. But because of how the comb teeth interfere, the information is compressed in the frequency domain and expanded in the time domain. The spectrum can then be read out with a suitably fast photodetector.

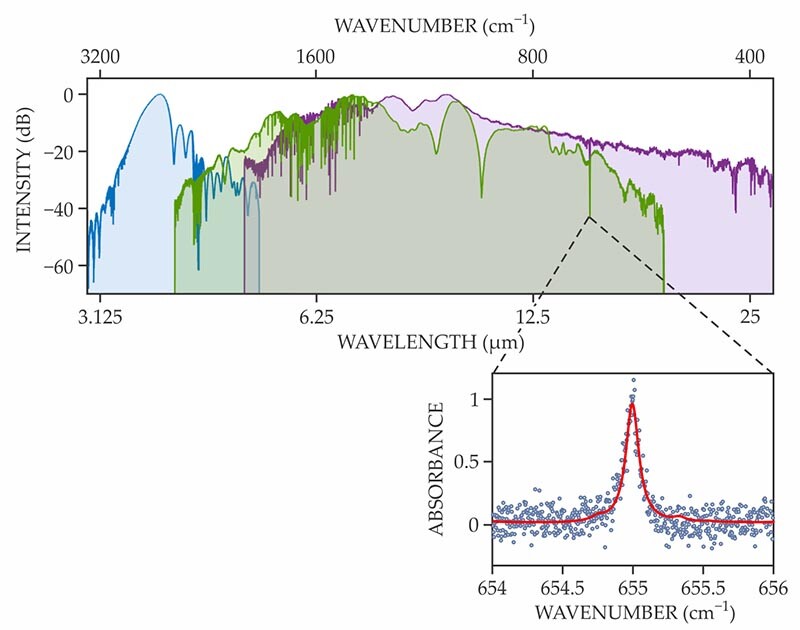

The figure shows a spectrum the researchers took of a mixture of important atmospheric compounds, including water, carbon dioxide, and methane. The colored lines represent detection using three different nonlinear crystals, each operating over a different portion of the mid-IR. The lower panel shows a close-up of one absorption feature in CO2: Data are shown in blue and the modeled spectrum in red. The broad spectral coverage is accompanied by resolution as fine as 0.003 cm−1. (A. S. Kowligy et al., Sci. Adv. 5, eeaw8794, 2019

More about the authors

Johanna L. Miller, jmiller@aip.org